New York City August 2023

So after a hiatus, I am gearing up for the next stage in my Research England supported ‘Knowledge Exchange Violin’ project. For the past few weeks, I have been in the USA, gathering ideas and inspiration for this next stage. In addition, I have been having workshops with objects, institutions, people and places who make up the next leg of the project.

What is Knowledge Exchange Violin?! It’s a very good question, and best answered by links to the two previous posts about stages one and two of the project, in 2022.

Stage One: https://www.peter-sheppard-skaerved.com/2022/06/knowledge-exchange-violin-2022/

Stage Two: https://www.peter-sheppard-skaerved.com/2023/01/knowledge-exchange-violin-2023/

One of the broad themes of the project is the our dialogue with nature, with the landscape. The violin, a wooden object which brings

Violin by Joachim Tielke (German, 1641–1719)

together the beauty of maple and spruce with the euclidean and ionic formality of its design, expresses this counterpoint, this tension, very deftly. And music itself, manipulating wildly uncontrollable harmonics, beats, and resonance with precisely notated and articulated control, offers a similar model Just look at the back of this Joachim Tielke violin at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. This extraordinary violin was made in the free city of Hamburg in 1685, the year of J S Bach’s birth. Telemann and CPE Bach would later make their mark on the city, and compose brilliant works which celebrated its trade and characteristics. It’s likely that this exquisite violin met one, if not both of these two friends.

You might be surprised to learn that I showed you the least decorative, or the least decorated part of this instrument, the one-piece back, made from bird’s eye figured maple. But I have good reason, and it is a reason which has resonated throughout all the making of art, and increasingly has made itself the prime mover of ‘Knowledge Exchange Violin’.

The way I see it, is this: every artist comes to the realisation that, at every moment, nature reveals and discards more beauty, more truth, more wonder than we can, individually or collectively hope to achieve in a lifetime or en masse in all of our lifetimes. Every great artist or fabricant will, to a greater or lesser degree acknowledge this in the the way that they work, and work with their chosen materials. Just think of the relationship, between the intricacy of Max Ernst’s detail work, and his incorporation of natural ‘squashed-paint’ figuration into his work.

Now go back and look at this exquisite back – with its beautiful red ‘ground’, the delicate arcs and arches of the ribs and bouts, the fine marquetry of the ‘purfling’ (the three strip inlay which articulates the edgework of nearly all cordophones). We have to be honest: all the labour which has gone into those features pales alongside the interplay of the knots, grain, and whorls of the maple. The work of the artist is a mere cupbearer to natural royalty and grace.

So the back of this violin can seen as a model, a paradigm of the delicate balance which should exist between human achievement and the

Moenkopi Sandstone, Capitol Reef, Utah. October 2022

world we are part of. Near the beginning of Knowledge Exchange Violin this was thrown into high relief when I had the chance to spend time in Utah, on Capitol Reef, with composer Michael Alec Rose, who is central to this project. The beauty and grace of this extraordinary geological uplift had an immediate parallel to the physical beauty of the violin.

But in addition, the sense of our smallness, our insignificance in the face of the scale and the deep time of these formations seemed to mirror my place in relationship to the art which I study and make.

But, it is, I think, fair enough to say that all of this was through into even sharper, massively deeper relief this summer with another trip to the American Southwest, from which I have just returned. The writers Garrison Keillor, Malene Skaerved and I travelled the slow way, across the USA, across the Great Divide from New York to Arizona, by train, and found ourselves standing on the rim of the Grand Canyon.

But I will come back to that. Alongside the exchange between nature and art, other counterpoints, confluences and offsets weave through my little project. Most of them, of course, are very much part of my work as an artist: the most obvious of these is Collaboration, in its many forms and scales. As we travelled across the USA this was on my mind, as I knew that I was about to say goodbye to one of my most treasured, long-term collaborators, the Wisconsin-born composer, Gloria Coates. As we travelled across the mesas of New Mexico, on the South West Chief train from Chicago to Flagstaff Arizona, Gloria’s piano quintet was ringing in my mind, most particularly a performance we gave in London, a year before the Covid-19 Lockdowns began. Here are the two – music and landscape – together.

So, to get things moving on this next stage of Knowledge Exchange Violin, here are some things to look out for over the next few months, in no particular order

- Filming with composer Jim Aitchison at Trememheere Sculpture Park, Cornwall UK

- Filming and recording on the Paganini violins (del Gesu and Vuillaume) in Genoa, Italy

- Filming and Recording on a new group of instruments at the Metropolitan Museum, New York City, USA

- Performing and Filming at the Pharos Trust Edward Cowie Bird Portraits and educational projects on music and the environment, Nicosia, Cyprus

- Filming and recording on Amati and Stradivari at the LIbrary of Congress Washington DC

- Filming and Recording at RSPB Leighton Moss, Cumbria

- Filming and Recording at the Schubert Club Museum, St Paul Minnesota

- Workshops and talks at Wheaton College, Illinois

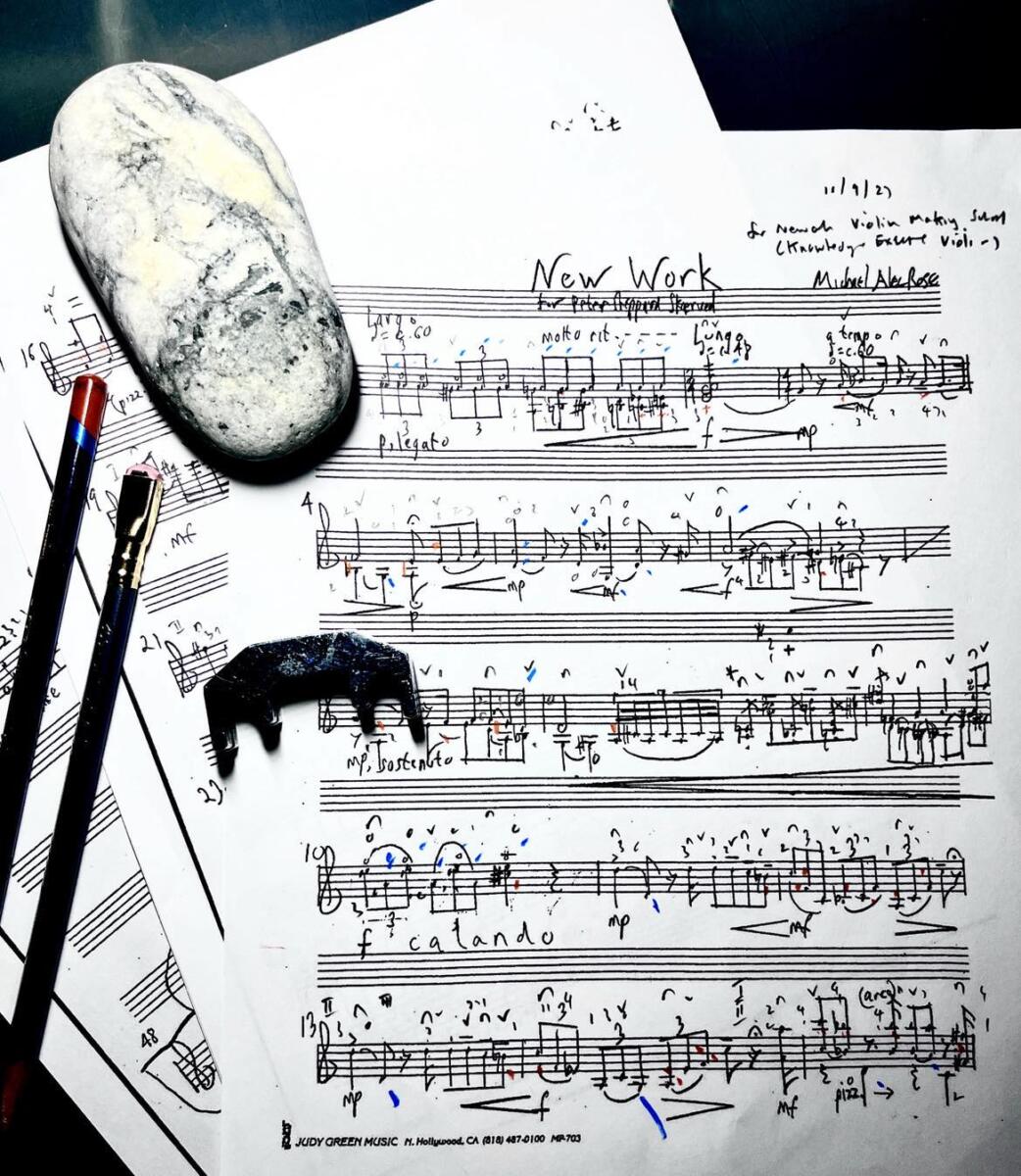

- New works from Michael Alec Rose

- Filming and Recording at the Stradivari Museum, Cremona, Italy

- Filming and Recording at the Newark Violin Making School, Newark, UK

- Workshops with composers and performers at the Zagreb Music Academy, Croatia

At the desk today (28 August 2023) here in downtown New York City – a glimpse of Michael Alec Rose‘s latest piece for this project. This written for, inspired by, and will be filmed on the Paganini del Gesu ‘Il Cannone’.

All human activity from the large to the small scale, folds me back to the extraordinary insight of Jacob Bronowski, which I first heard, when I was seven or eight and saw ‘The Ascent of Man’.

“Man is a singular creature. He has a set of gifts which make him unique among the animals, so that unlike them, he is not a figure in the landscape, he is the shaper of the landscape.” — Jacob Bronowski

This statement, profound though it is, is not without its problems. I wonder what Bronowski would have done, had he made his brilliant series 40 years later, or now, when we can all see and feel that disaster of this ‘shaping’. And now, of course, there is far more awareness of how other animals continually shape the landscape, for better and worse. But taking the long train trip to Chicago, and then to Arizona forces us to think about what the balance of this relationship was: as we crossed the mesas of New Mexico, I caught sight of one of the farmed Buffalo herds that now can be found on Colorado-Mexico border. The transcontinental railways, the engineering triumph of the 19th century, destroyed the lives of countless Native Americans, and many millions of buffalo, which had roamed free on the Great Plains since the ice ages were driven to near extinction in a massive slaughter enabled and encouraged by the railroads.

This contradiction lies at the heart of so much of the work of the artist, and it is one that I hope that Knowledge Exchange Violin can scrutinise. About 10 months ago, I spent time walking on Capitol Reef, Utah, with the composer Michael Alec Rose, whose work is so

Maud Powell (centre)and pianist Arthur Loesser, photographed from the Kolb brothers studio at the Brightangel Trailhead, riding down into the Grand Canyon in 1916

fundamental to this project. I think that I can confidently say that I found enormously comfort in a landscape where my presence was moot. But our rail trip across the country was aimed at perhaps the most famous of these landscapes, and I felt, that as well as the two writers with me, there was someone else, the violinist Maud Powell. When my wife and I began our trek down the Brightangel Trail, beginning the 5000 foout 1700 million year descent to the Colorado River, I certainly felt her alongside me. Indeed, it is not possible to travel to the American Southwest, without hearing the stories of extraordinary individuals, who explored this part of the Americas in the 1800s: and one of them, John Wesley Powell, who was the first person to successful travel the whole length of the Colorado River, was Maud’s uncle. Indeed he namedcreek and canyon in eastern Utah, noted as the western starting point of the Ninemile Canyon petroglyphs section of the Canyon, for his niece ‘Minnie Maud’.

But now it is time to start digging into Knowledge Exchange violin in earnest. Cornwall beckons, and it will be exciting to see where the ideas take me next.

Tremenheere Schulpture Gardens. An extraordinary day in England’s far West, 8 9 23

At the beginning of the year, I travelled to Cornwall, to meet with my long-time collaborator, composer Jim Aitchison, so explore the possibilities to be found in an extraordinary place near Penzance. Tremenheere, in Cornish which was last spoken in 1700, means Place (Tre-_ of the Standing Stones/Menhirs. It can be found a few miles outside Penzance, on a piece of land sloping down the wooded hills to St

Filming Bach in the Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens, with Immo Horn. 8 9 23 Photo Malene Skaerved

Michael’s Bay, and looking at St Michael’s Mount, to the South East. The depth of history, even of just human history, in this area, is beyond reckoning – there are so many stone and bronze age sites between Tremenheere and Lands End, just ten miles west, that they still have not all been explored and studied. But there’s another complicating factor. This area has been densely and continuously inhabited and worked for so long, that it is often impossible to date stone (often granite) artefacts and structures. If a vast granite boulder has been used as the cornerstone for a series of buildings for thousands of years, without interruption, then, from a historical point of view, it is almost impossible to find purchase in the object, to date it, or to even decide what dating it would mean.

Our host for the day is an extraordinary man. Neil Armstrong has worked as a family doctor in Cornwall for over 40 years. Somehow, whilst doing this (and his work and philosophy as an MD lies at the hear for everything he does), he found the time, belief and energy to make Tremenheere. Talking to him, the achievement is almost unbelievable. Just clearing the land of brambles and rubbish, before any ‘making’ could begin, took six backbreaking years, weekend after weekend. Neil says that, in all honesty, the most important artists that he has worked with, have been his digger/backhoe drivers. It was difficult to not have Bronowski in my head again (see above). One of the chapters in his ‘Ascent of Man’ talks about the extraordinary ‘Watts Towers’ in Los Angeles, which an immigrant Italian, Simon Rorida, built singlehandedly over a 33 year period from 1921-1954, from found materials (chicken wire, railway sleepers, cements, steel rods, tiles – ‘anything that he could find or that the neighbourhood children could bring him’ TAOM 118). Rodia said:

‘I had in mind to do something big, and I did. You have to be good good or bad back to be remembered.’

As Bronowski observed , ‘The Human Hand is also an instrument of vision. It reveals the structure of things and makes it possible to put them together in new, imaginative combinations. But of course the visible is not the only structure in the world. There is a finer structure beneath it’. In the case of Neil Armstrong the ‘finer structure’ is his burning belief, his personal philosophy of the relationship between art, landscape and healing. This is inescapable, if you spend time in his creation, and shone through our conversations, on and off camera, with him. As we walked around the woods, fields, semi-tropical valleys, and wetland which make up the park, the depth of his relationship with the land, the art and the people who have touched it became clearer.

A vignette: we were standing talking by a wonderful David Nash grouped sculpture in the beech-wood section of the park. The conversation began with the way in which the sculpture had been made for the park. Nash had suggested a group of carbonised oak stumps, from his

David Nash – Black Mound (Photo Malene Skaerved)

collection. We talked about whether this was a family, or a conversation (privately, I had the – Cornwall-based – Barbara Hepworth ‘Family of Man’ in my mind). Then we talked about charcoal, in the forest: of course, there would always have been charcoal-burners in the woods. But then, Neil told the story of one of his patients, a man he had known for many years:

‘One day, he ran me up, and said, Neil I would like to see you, today if it is possible. I will be dead in a couple of days. So I went to see him, and he told me how grateful he was for my friendship and help – he was sitting up, seemed fine- and two days later, after saying goodbye for his friends, he was dead. He was 95. What a wonderful death.’

Without too much preamble, Neil had illustrated one of the real powers of the art, of the space he has made. This is a place where life and death, where healing and peace can be found in the dialogues between nature and art.

The Church of St Antony. Gillan Creek. 530 am September 8th 2023

Our long day the west of Cornwall had taken me back to how important this conversation had been for me, particularly reflecting on a landscape that I know very well. Driving overnight, Malene and I reached the Lizard Peninsula at about 5 am, and droved south to the oak lined creeks and inlets south west of Falmouth. The sun was far from up, but parking the car next to the hamlet church of St Antony, I was overwhelmed with the atmosphere and fragrance of a place that I know better than any other landscape.

For the first two decades of my life, thanks to my parents, I spent summers camping on a sandbank on Gillan Creek, just south of the Helford River, of which it is the smaller, (if possible) even more enchanted sibling. The extraordinary atmosphere of sessile and common oaks stretching down to the water, endless tidal lagoons and mudflats to explore, sailing the (actually quite dangerous) waters of Falmouth bay in the dinghy my father built, became a wondrous normality. And, even though I have only visiting briefly, once or twice in the last three decades, this is still the countryside and waters that I know and love the best.

But it was architecture and music, in conjunction with wildlife, rock, sand, mud and water, which really first made sense to me there. The church of St Anthony is almost on the shoreline, tucked behind the old piggeries and farm buildings which are now a chandlery and holiday apartments. It’s actually below the highwatermark, and on supermoon springtides has been known to flood. This explains the simple stone flow and rattan mats. But, from the age of 10 or 11, I would bring my violin along the beach, and play the violin for hours under the wonderful 14th century barrel roof (typical of the area). People would wonder in from the beach and find a barefoot boy scratching his way through acres of Bach. I suspect that it was a terrible noise, but I was never worried about people hearing me, and loved finding different spots (light, acoustic, medieval stone and wood to look at ) to play. I think that I can say that my love of the violin alone, was born here. I have not found a place that I love to play more than this. I have to get back…

The churches of this part of the Lizard peninsular have a particular relationship with the earth, with the sea and sky, with nature. The two I know the best are, of course, St Anthony, and the church of the village of Manacaan, about 40 minutes walk away. When I read Philip Marsden’s Rising Ground, which documents his relationship the landscape of Bodmin Moor, off the east, I recognised his observations of hour old buildings were often groined into the landscape, so that they were not at risk from the historically savage weather that can afflict this exposed isthmus-county. St Anthony is tucked into a tree covered cleft between the Celtic fort of Denis Head and Bosahan Hill. The hills and trees are its protectors. Manacaan, which has a Romanesque south door is a hill-top church, and surrounded by ancient Yew Trees. Miraculously, a large, tall fig tree grows from the south wall of the church – it is documented in the 1700s, so it is fair to assume that it has been there for 300 years.

Why is all this relevant? I think that I am comfortable with saying that the balance, the counterpoint, the conflict and harmony, between humans and nature, however it is expressed, is vital to my project. This ancient landscape is completely manmade. In his The Lost Rainforests of Britain Guy Shrubsole drew attention to these oakwoods as the epitome of a vital environment which has been largely overlooked by the ecological movements to date. However, Shrubsole pointed towards the wonderful final work of a ‘wise man of the woods’, Oliver Rackham The Ancient Woods of the Helford River. This work, which was unfinished at Rackham’s death and completed by his admirers and friends, is a lyrical survey of the the valleys and inlets I love so well, with Oak trees, ‘Crooked and branchy … full of bryophytes, with polypody growing on limbs and even high in the crown.’ Rackham pointed out, that the very character of this ancient oak and hazel woodlands was the result of it being the work of the humans: the reason that the mightiest oak cover is thickest where the lichen and moss covered boughs dip into the water, is that there where planted thickest there to mark a boundary, and, perhaps to prevent animals from staying onto the mudflats. We have a great history of working with the natural world. Our art and culture has always spoken, sung and painted of this history. We should continue: and the achievement of Neil Armstrong at the Place of the Long Stones, is part of that great tradition, as much as the work of the great violin builders celebrates and gives voice to the beauty of timber and the song of the wind in the trees and the roar of the sea.

Sunday 10th September

Knowledge Exchange violin is multi-layered, and the various parts of this expanding and ever-focussing project fold in themselves and illuminate their shared and discrete themes. I am working with Newark Violinmaking School, and my dear friend Ben Hebbert, towards a day of filming with students and teachers there. This will expand on the theme of violinmaking, but this time with a stress on the dialogue between great instruments of the past and living/emerging makers.

Here’s the newest work from Michael Alec Rose for the project, which meditates on this upcoming adventure and associations with a violin which will be at the centre of this exploration. More on th

Michael Alec Rose’s brand new work for Knowledge Exchange Violin ‘New Work’, inspired by upcoming collaboration with the Newark Violin-making School (Michael loves rocks, so here is a marvellous pebble I picked up on Marazion beach on Friday Morning)

28th September London

The past couple of weeks have been a flurry of preparation and organisation for the upcoming set of Knowledge Exchange Violin happenings in Cyprus, the US, the UK and Croatia. So I will report back on those as they happen. First of all, something small, but related to the project. On the 13th October I am playing a concert of works by Sadie Harrison, Jeremy Thurlow and Robert Saxton at Robinson College Cambridge. If you have been following the evolution of Robert Saxton’s new solo sonata ‘Reflections in Time’. This work evolved during the course of the

A gaggle of my notebook pages which will be exhibited at Robinson College Cambridge when I play works by Robert Saxton, Sadie Harrison and Jeremy Thurlow in a couple of weeks 27 9 23

first sets of Knowledge Exchange Violin, and is, in part related to my drawings. The exhibit will be six frames of notebook pages of drawings and paintings running over the turn of the year 22-23. There are storms on the Mississippi, bird songs in the woods of upstate New York, and, of course, my constant, the tidal thames at the end of our lane.

The dialogue between music and art is one of the underlying threads of the project: it was pointed out to me that I had not spoken about how this dialogue works in my practice, so while we were at Tremenheere, a couple of weeks ago, Jim Aitchison, directed by Malene Skaerved, interviewed me specifically about this process. I can’t be sure that the answers which I gave were coherent, but maybe, they offer a start, and Jim’s questions were great.

Cyprus 30th September – 5th November

Cyprus is one of my artistic homes. To get a small idea of what I feel about it, you could go to my blog about my last visit, four years ago, just before the pandemic struck. Here’s the link https://www.peter-sheppard-skaerved.com/?p=27064

As will be clear from the film above, returning here has reminded me of a number of vital ideas (for me) which now are finding their way into Knowledge Exchange violin, particularly our engagements with the layers an palimpsests of history. I will return to this. However, after

Conversation with filmmaker Anna Thew, at The Olive Grove, Cyprus 1 9 23

arriving late on a Saturday night in the capital, my dear friend and host, Garo Keheyan and I whizzed off, Sunday morning, to Governer’s Beach, to swim in the crystalline waters. and then to the Olive Grove/Delikopolis, and then returned me to the mountains and woods which enliven my project.

Fascinatingly, when I arrived at the Grove I met two of Garo’s oldest friends, the British experimental filmmakers Anna and Martin Thew. The conversations with them, on every subject from Italian renaissance poetry to trees were wonderful: but one Leitmotif came to dominate our conversations, and reflected of the themes of ‘KE Violin’ – the question of the Durability of Art and the materials that Art is made from. I realised that there was/is a direct correlation between Anna’s explanation of the challenges of preserving analogue film (which begins to degrade within two decades) and the questions as to what and how we activate and/or preserve our cultural and natural history. Right back at the beginning of this project last year, I had an enlightening conversation with RSPB Reserve director Jon Carter about the contradictions and challenges of ‘preserving’ and ‘conserving’ a wetland. His point, made so powerfully then was these two ideas were in many ways anathema: in order to keep a wetland as a wetland, it is necessary to prevent it doing what wetlands do, to develop and change (in the case of Leighton Moss, next to Morecambe bay, this would mean filling in naturally and turn into scrub, and eventually woodland). In order to preserve it as a wetland this natural process has to be derailed/reversed and nature made static. Anna described the loss to the natural beauty of analogue film, when in ‘restoring’ it, it is digitised (the dark colours lose richness, vividness). Some is preserved, but not the fundamental beauty and integrity of the medium. I will not attempt to articulate the elegance and detail of here explanation, but it really deepened my understanding of my project.

Here is the programme that I played at the Olive Grove on the first night, with the explanation of its rationale.

Giovanni Battista Viotti – ‘’Ranz des Vaches’ (1795)

Sadie Harrison – ‘The Flight of Swallows’ & ‘The Writing Cabin in the Woods’ (Gallery) 2011

Slåtter & Hallinger (Country Dances) Traditional Norwegian

Olivier Messiaen – Bird Transcriptions (1958)

David Matthews – Australian Birds (2010)

Peter Sculthorpe – ‘Alone’ (1974)

Edward Cowie – ‘Menurida Variants’ (2020)

Michael Alec Rose – ‘Two Rivers across the Pond’ (Sedimental Education) (2022-23)

Heinrich Ignaz Biber – Mystery Sonata XVI ‘Schutzengel, Begleiter des Menschen’ (1688)

David Miller (Ithaca College) – Musician Wren (2023)

Peter Sheppard Skærved writes: ‘It is a delight to return to the Olive Grove. Over the years, it has been my privilege to spend a lot

One of my favourite places to practice. At Garo Keheyan’s Olive Grove 1 10 23

of time in this enchanted place: so much music and so many inspiring concerts have happened here. It is one of the places that continues to inform my ideas about music and the landscape, art and nature. I am profoundly grateful to Garo Keheyan for this continuing inspiration./Tonight, I will play pieces reflecting on our relationship with the world we live in. Over the past year, I have been on a quite literal artistic journey, ‘Knowledge Exchange Violin’, which is supported by Research England. This work involves collaborations with organisations and institution on both sides of the Atlantic. A few examples: in the United Kingdom I have been working with the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, making films with the nature writer Laurence Rose on the vanishing Heathland outside London, recording and filming on the instruments at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and exploring the extraordinary natural environments and installations at the Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens in Cornwall. In the USA, I have co-curated an exhibition on French Revolutionary music at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, recorded and filmed on the instrument collection of the Metropolitan Museum in New York City, worked on Birdsong projects with the students at Ithaca College, walked and made music in response to Capitol Reef National Park Utah, responded to the extraordinary collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC – there are many more collaborations, and the work with Pharos, is a vital part of the project./A theme running through the Knowledge Exchange Violin is our relationship and responsibility to the natural world. Working with historic instruments, for instance, provokes and informs these ideas: an Amati violin celebrates the beauty of the spruce and maple from which it was made, at the same time setting them in a classicising frame. The grain of the wood on such a 400-year-old violin is a visible document of hard winters or drought, even of lightning strikes. Playing the violin sets the materials back in motion, recalling the life of a treen before it was felled, what Laurence Rose called ‘Pine Tree Counterpoint’ in one of the films we made. And of course, the instrument, the music, demanded the destruction of at least one tree./Of course, musicians, writers and artists have always been inspired, taught by nature. Music is full of the sounds of birdlife, of animals, of weather, the sounds of the sea and the earth. There are fascinating, even troubling overlaps between the imitation of nature, of mimesis, and nature as inspiration. The pieces I will play tonight explore some of the ways that these inspirations can work. Giovanni Battista Viotti responds to music heard in an alpine environment, Edward Cowie is inspired by a Lyrebird which had learnt snatches of Haydn Symphonies, Olivier Messiaen collects birdsong, Sadie Harrison responds to the flight of Swallows over Munich. And all of this will happen, be heard in this extraordinary environment, this landscape, teaching us still.’

And then back to Nicosia. I realised that I had a couple of days, comparatively solitary, to reawaken my fascination and research into certain aspects of this city, which fascinate me. Here’s one of the examples from a visit, six years ago.

With Roderick Chadwick and teacher/students from the English School in Nicosia 4 10 23

One of the most inspiring aspects of working with the Pharos Foundation is the chance to work closely with young people in educational workshops. On the day of my concert in Nicosia with Roderick Chadwick, we worked with a small group of students from the English School in the City. This proved to be stimulating and thought provoking.

The substance of the workshop as we presented it, was the exploration of the imitation and incorporation of nature in music, with, as in our concert programme, birds and birdsong at the heart. We played them Biber, Sadie Harrison and Messiaen, and their insights into the music and the ideas behind it were extraordinary.

One particular idea which emerged from the workshop pertainethe d to the geographical specificity of cultural references and imitation in arts. This was far from the first time that this has come up in my international work, but every time I encounter it, it raises exciting and challenging questions about the old saw of ‘music as an universal language’. On this occasion, the reference was to the song of the Cuckoo, which is so poignant, as an indicator of the arrival of summer for anyone from Northern Europe. I was playing and talking about the Biber Sonata Representiva, and when I reached the second bird which the composer imitates, which is the Cuckoo, there was not a glimmer of recognition from the students or their teacher. None of them had any idea what this bird was, or what it sounds like. Of course, the English association of the cuckoo to the poetic and musical idea of summer is anchored in English culture. After all the archetypal folksong, the round Somer is icumen in, first written down in the 13th century, begins with this very bird.

Svmer is icumen in

Lhude sing cuccu

Groweþ sed

and bloweþ med

and springþ þe wde nu

Sing cuccu

Perhaps the song of this bird is all the more poignant for us, as the bird itself is reclusive: most people have heard a Cuckoo, but very few have seen one. In the case of our Cypriot musicians, they had neither seen nor heard one. It’s imitation by Biber, or anyone else, in music, is moot.

There were many other aspects to the workshop, including the issues of blasphemy when it came to the eating of Ortalons, in France. And

Messiaen’s bird transcriptions on my practice desk. 2020

the chance to hear Roderick talk in depth about his work and research into Messiaen’s Catalogue d’Oiseaux, was one I seized with enthusiasm: he is the living expert on this music.

After the workshop, we dashed over the radio station for an hour-long interview with Saskia Constantinou about our evening programme of Robert Saxton, Biber, Messiaen and Edward Cowie. Her sensitive questioning and the ensuing conversation took our ideas to an new level.

One issue which really come to the fore was the issues of whether or not new music and art was dramatically more challenging than the old? We turned the question on its head an asked why it was that people have become accustomed to music, for instance, by Beethoven, and fail to recognise that it is challenging, exciting, difficult, revolutionary. I passionately believe in NOT allowing the silo-ing any musical or musical disciplines. I can be as shaken-up, excited, and even offended by old music, even ancient music, just as much as by the music of the past century and our own time. There’s not reason that living composers should smooth themselves out in order to give a pass to the sensitivities of modern listeners. After all, Haydn and Berlioz certainly didn’t. Here’s a link to the interview https://fb.watch/nwNw99Mbjh/

The concert that evening, at the wonderful ‘Shoe Factory’ venue in Nicosia, focussed on bird song. At the nexus of the first half I played Heinrich Biber’s Sonata Representiva . Here’s what I wrote about the piece for the programme book:

Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber (1644-1704) – Sonata Violino Solo representativa (1669)

The imitation of nature is the well-spring of what we do of artists, and the birds have ever been our teachers, not only in as musicians, but for artists and writers as well./For many people today, the very first violin concerto they will hear, and certainly the one that most people will instantly recognise, is Antonio Vivaldi’s E Major Concerto ‘La Primavera’ (Spring). And the very first time that the solo violin(s) breaks away from the orchestral mass, in that piece, what is heard, according to the sonnet appended to the score, is the song of the birds (‘canto dè gl’uccelli’): ‘festosetti La Salutan gl’ Augei con lieto canto’ – festive, they celebrate the return of spring with joyful song. And what the solo violins play is not, melody, but trilling, interweaving bird song. The first musicians celebrated in the first entry of this most celebrated of violin concertos./Curiously, in the last one hundred years, string instruments became wary of imitating the birds. There have been notable exceptions, most especially the second violin concerto by the great South African-born Priaulx Rainier, Wildlife Celebration, commissioned by the celebrated naturalist and writer Gerald Durrell./But Vivaldi was far from being the first composer to bring the song of the birds to the violin. In 1669, the Salzburg

St Francis talks to the birds (including a Blue Tit, Goldfinch, Jay, Parakeet and Cuckoo) North Germany late 14th Century Courtaul Institute

virtuoso violinist-composer Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber (I644 -1704) wrote his Sonata Representiva, which introduces and imitates a Nightingale, a Cuckoo, Chickens, and a Quail … alongside Frogs, a Cat, and a march of Musketeers (purloined from his ‘Battaglia’ for orchestra). Just as in Vivaldi, great attention is given to the verisimilitude of the violinistic imitations, and this is something that stretches back to the world of medieval paintings and illuminating manuscripts. In London’s Courtauld Institute Gallery, there is an anonymous early 14th century Triptych, most likely painted by a for a Franciscan house in Germany. The human figures are relatively crude, but in the lower left-hand panel, St Francis preaches to the birds: and they are a recognisable to any bird watcher – a Goldfinch, a Great Tit, a Little Owl, a Jay, a Blackbird, and over the saint’s tonsured head, Blue Tits fly. I like to think that they are singing back to the saint, like the ‘smale foules a gret hep’ that wake the writer, Geoffrey Chaucer in The Book of the Duchess written ca.1370. Chaucer, like Vivaldi, loved the way his ‘…chambre gan to rynge/Thurgh syngynge of her armonye; /For instrument now melodye/Was nowhere herd yet half so swete/Nor of acord half so mete…’./And Biber’s witty, trilling sonata, might have been the birds at the end of Geoffrey Chaucer’s bed, or flying about St Francis’ head!

Composer Edward Cowie talks about nature and music, before our performance of his Bird Portraits. Shoe Factory, NIcosia 4 10 23

After the concert, and the simple meal which followed our exertions, Evis Sammoutis and I snuck out of the Shoe Factory and recommenced our explorations. There was a reason, and it was an exciting one.

Roderick Chadwick rehearses Messiaen at The Shoe Factory, Nicosia, 4 10 23

I have been thinking about the degree to which the back has been turned to French Cyprus. Of course, there has been a very good reason for this: when a culture leaves apparently no descendants, no legacy, no one to celebrate its presence, it is not difficult to understand why present generations might see no motivation to celebrate it. Of course, this is coupled to an extra factor, that of non-connectedness. The Lusignan Dynasty, however long they stayed, (1192 – 1489) were, it seems, always seen as interlopers, aliens, on the island: ensuing Venetian (1489 – 1570/1) and then the Ottoman invaders (1571 – 1878) would have had no reason to associate with their legacy. Indeed, from an architectural point of view, the Ottomans, in adjusting the medieval structures to their purposes and aesthetics (driven of course, by Islamic diktats) perforce removed the character, the face of the culture which the Lusignan dynasty had left behind. And successive administrations naturally enough sought, where they could, to obviate the Islamic face of the island , which had been, to all intents and purposes, founded in the architectural infrastructure and décor of the French era, however destructive that founding had been. Even in the 1930s, Rupert Gunnis could write about the 300 year-long Lusignan era, which he described as the ‘most brilliant’ of the island’s history that:

‘It was, however, entirely a foreign, ie a Latin brilliance: of the fortunes and aspirations of the local inhabitants we hear nothing. Reduced to the position of mere vassals of the new dominant class …’ (History Of Cyprus 1936 P. 15)

So repeated palimpsestic activity reduced the imprint of this period significantly by the late 19th century. This problem was heightened by the growth of two conflicting aesthetic and political movements in the last 150 years – Orthodoxy and Hellenism. As Patrick Leigh Fermor observed in a number of his works, the incessant Kulturkampf between these increasingly powerful entities resulted in the obscuring, even the purging of much of the cultural diversity of the Greek Peninsular. The ‘bitter lemons’ of Cyprus in the mid – twentieth Century only inflamed this process (1955-60 Guerilla War against the British, 1963 proposed constitutional changes ending powersharing between Greek and Turkish Communities, 1964 UN Peacekeeping force/ Turkish Cypriots withdraw into defended enclaves, 1974 Military junta in Greece backs coup against President Makarios, who flees. Within days Turkish troops land in north. Greek Cypriots flee their homes, 1975 Turkish administration in the North) re-toxified at least one historic animus. Ever-more binary notions of national identity came to dominate the status quo so much that only those histories which fit today’s narrative were/are tolerated. There is less hope for an awareness of Lusignan in today’s Cyprus, than there is for the opposing camps on either side of the buffer zone to accept how essential both cultures might are for the richness of the Island.

Of course, this is an outsider’s point of view: b

The tiniest of echoes. The Ömeriye Hamam (a bath house erected in Mustapha Pasha), the footprint, lopped-off gargoyles, stone work and archways of the Augustinian Church of St Maria, can just be felt, if not seen.

ut perhaps I am lucky. I have no skin in the game, and my ignorance, my insensitivity to emotional issues which can bedevil any discussions of these historical dynamics, might be an advantage when shining a light on a small corner of the strata of narratives, finding some way to make it live today.

So Evis and I walked along Ermou Street, and turned south along Pentadaktylou street. where the view has been obstructed by a monstrously kitsch Orthodox Cathedral of St John, completed in the years since I was last here, a dramatic statement of the primacy of Orthodox power and money, completely out of scale with the predominantly intimate size of public buildings and houses in Nicosia. But, curiously, this horror and a glass-box municipality building a block and a half to the west, frame and focus an extraordinary historical site between – the outlines and remains of a cluster of medieval houses and religious buildings. This archaeological site has been exposed to the elements for all the years that I have visited the capital, but now it has been, to a degree ‘made good’. No longer does it give the impression of at once building- and bombsite (neither of which it was), but has been carefully presented, with well designed walkways and view platforms giving overview to the more interesting parts of the site.

As is always the way with cities which as TSE observed in his ‘East Coker’:

In my beginning is my end. In succession

Houses rise and fall, crumble, are extended,

Are removed, destroyed, restored, or in their place

Is an open field, or a factory, or a by-pass.

Old stone to new building, old timber to new fires,

Old fires to ashes, and ashes to the earth

Which is already flesh, fur, and faeces,

Bone of man and beast, cornstalk and leaf.

Houses live and die: there is a time for building

And a time for living and for generation

And a time for the wind to break the loosened pane

And to shake the wainscot where the field mouse trots

And to shake the tattered arras woven with a silent motto.

And with these successive fallings, we, as Evis and I were, look DOWN onto history. It’s not that cities sink with time, but that the agglomerations of refuse and rebuilding, raise the road levels, century by century. S. Clemente in Rome is a powerful illustration of this, and the largest church (excepting St Pauls Cathedral) in London’s Square Mile, St Bartholomew the Great, is all but invisible until you are up-close, so much have pavements risen about it in the millennium since Rahere dreamed his dream.

Evis and I were looking down at the East End of a fascinating little church, which illustrated one wonderful aspect of changing mores and

Seeking out the echoes of Lusignan Cyprus

All that remains of the sacristy and ambulatory of an early 13th century French church in the old town here in Nicosia 4 10 23

religion-driven architecture. Examining the roofless sacristy of this church, it was clear that the Lusignan rebuild had repurposed the original form and function of the building, to charming effect. And one of the reasons was the need to walk. A somewhat-abbreviated information panel informed us that part of the church was probably 10th century, Byzantine, and the other was French. The great Byzantine churches of Istanbul, which incorporated the basilica form not to be found in the works of the Emperor Justinian, whatever their size, include a semicircular apse behind the altar. In the case of the ‘Hagia Irene’, the seating in this apse could also be used for ecclesiastical conclaves, for committee meetings (to discuss how many angels might dance on the head of a pin, no doubt). However, late Romanesque and early Gothic churches from St Nidar in Trondheim, and to St Bartholomew’s itself, offered space behind and around the sacristy for walking, and whilst walking, for contemplation, for discussion.

In some ways, this was the Christian revival of Socrates’ ‘Periaptos’, the oval colonnade around which he walked and talked with his students: the ‘ambulatorium.’ Looking down into the little church building beneath us, Evis and I could see that, the French architects had preserved the little apse of the Byzantine church, and built a demi-hexagonal curtain around it, resulting in an ambulatory, with just enough space for two monks to walk and talk.

The old church had been ‘wrapped’ by the new – and the larger scale of the Lusignan carapace perhaps offered the possibility of side aisles, more air and light, as can been seen in countless English churches of all sizes.

Sometimes the layers of history are not laid down strategically, as it were, time-upon-time, but wrap themselves around the past, investing, ensconcing it.

Rupert Gunnis wrote of the vanished Lusignan nobility:

‘Where now is Nores? Where d’Ibelin? Where Giblet? Gone in name perhaps but not blood; somewhere run these noble strains; diluted and thin they may be, but they are there. The peasant in the village, the policemen in Nicosia, the fisherboy at Paphos, or the priest in the Carpass may, if they knew it, have bluer blood in their veins that half the aristocracy of Europe.’ (Ibid. P. 33)

River Falls – Wisconsin 16th October

Looking South down the Saint Croix River, the border between Minnesota and Wisconsin 15 10 23

I was not able to add anything to this Journal in the last week, for the simple reason, that upon returning from Cyprus, I was thrown into a welter of concerts, travelling, workshops and teaching, which has now deposited me on the border between Minnesota and Wisconsin. This area has become one of the touchstones for the project, for a combination of reasons, ranging from the ideas about how music travels, through to relationship between art and natural world, which of course, mirrors our counterpoints with nature. The very first thing that I was able to do, literally an hour or so after touching down at MSP airport, was to be taken out on the Saint Croix river, by my friend, AJ Paron, to watch something quite mad, but playful, which I now realise, speaks volumes to this dialogue. Unlike the UK, there is a real feeling of linear connection between annual festivals in rural American and, I suddenly realised, is most obvious in the autumn, where the the celebration of Harvest Home, elides into the nuttiness of Hallowe’en. I had often wondered why the Hallowe’en decorations appeared so early, and the event I saw in/on the river at Stillwater, the ‘Pumpkin Regatta’, has clarified it for me. The first Hallowe’en decorations to appear in gardens, on window sills, on front steps, are organic – squashes and pumpkins. These, of course are the most durable, and to a degree at once the most visibly striking and less-than-useful-as-food of all the various crops. So they are placed outside, on show, initially, (even slightly unwittingly) as harvest symbols, and then, as October draws on, joined by ghosts, and faux-graveyards, witches and cobwebs.

One of the important distinctions between the manifestations of harvest celebration in Europe and the USA, is excess. This is not a decadent thing, but historic, with important typologies. At many stages, as the European settlers from the time of the Tudors onwards moved West across this continent, they were overwhelmed by the fruitfulness of fields, woods and waters of this new-found land. The first whalers to work in New England, around Nantucket and Mystic, barely had to leave harbour to get their prey, the forests and waters of what would be come Manhattan, were thick with game, and centuries later, when the settlers found their way to the prairies and woodlands of Minnesota and Wisconsin, the land was fertile, and, often, easily farmable. As predominantly Christian immigrants, many of them fleeing less-than-desirable situations, most particularly, poverty, this was, this is, ‘Canaan’, land of milk and honey. The result is that the subtle difference between an English and Minnesotan harvest celebration, is that ‘we plough the fields and scatter, the good seed on the land’, back home is rewarded with a sufficient harvest, a sign of God’s mercy and forbearance, whereas in the USA, what is celebrated, expected is superabundance, an overflowing cornucopia, and a celebration (at State Fairs the country over) of super-sized vegetables! So perhaps it would not be too surprising that, the harvest festivals here often include activities to utilize a superfluity of the over-large, and consequently inedible squash.

At Stillwater, and indeed at many other places, this is represented by the annual Pumpkin Regatta.

The Stillwater Pumpkin Regatta 2023

In addition to hardy souls who gamely paddle enormous hollowed-our pumpkins in front of the enthusiastic crowds gathered on the riverbank, harvest-excess is represented by other non-alimentary uses of produce. Pumpkins are smashed and thrown … and of course, all across the country, left out to become symbols of all-Hallows Eve- and very often in get caught in the massive deepfreeze of the Midwest Winter, under the snow and ice, reappearing with the melt at the final, and much needed arrival of spring, often the middle of april, ready for the process to begin again, barely more than four months later.

So after this welcome back home to the Midwest, I drove the 30 minutes south-east, to River Falls, where I spent 5 days with the community around the campus of the University of Wisconsin. Here are my thoughts upon arriving in River Falls Wisconsin

One of the most wonderful things about this project has been the in-the-moment response of my collaborators across the world. As seen above, my morning routine in River Falls involved a saunter in the dawn along a back alley to Waystone Coffee, who proved to make the type

The walk for morning coffee (Walnut Ave River Falls)

of caffeine I need to start my day. I posted pictures of this walk, and drew the dawn a couple of times. The astounding counterpoint between the oranges and reds of the Sugar Maples and the glorious sunrises, was simply too good to miss. And it seemed that it was making an impression online, as the the composer and poet David Hackbridge Johnson, responded to my ‘Pastoral, Alleyway, River Falls’ with a beautiful, delicate vignette for violin alone, with the same title.

This is not the first time that something wonderful like this has happened to me, but is is worth talking about, as it speaks to the power of the act of ‘sharing-through-transcription’ which Ferruccio Busoni wrote about so inspiringly in his 1911 ‘Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music’, which has been on my shelves since I was a teenager. My experience of this phenomenon, is that the composer sees, my version of an experience – articulated either visually or verbally, and then transcribes it (in the true sense) as, or through music. The outcome, and this has happened to me many times, with the work of Sadie Harrison, Robert Saxton and more (responding to my visual work), is that the resulting piece, when it happens, is performed, is shared transforms the initial experience, transfigures it, whilst, at the same time, making it revenant, live again.

Two days after the piece was written and sent to me as an attachment, I played it to a large audience in the Abbott Concert Hall at UWRF, alongside works written for me by American composers. Not only did I find myself back outside, in the dawn light, looking for coffee, but I felt the sigh of recognition, of grace, from the audience, who the composer had taken there too. This is what Art can do, when we all do it, together.

Here is the lovely piece that David Hackbridge Johnson wrote for me last week, after seeing pictures of my walk to coffee along a back alley in River Falls Wisconsin. He finished the piece on the 18th, and the time difference (6 hours) meant that I was able to work on it intensely the same evening – and then could get it onto the programme for my lunchtime concert University of Wisconsin–River Falls on the 20th. And of course, the audience loved this delicate homage to their town – as, I think will you! With thanks to Kris Tjornehoj for making such lively collaborations and inspirations possible!

Another priority for me here in the MidWest, was to bring the music of dear Gloria Coates (1933-2023) to the state of here birth. Here were my thoughts after playing the first of two performances of her solo music at the University of Wisconsin River Falls, on Thursday evening.

But the greatest thing about working here, as so often in my life, is the opportunity to be part of a community, to collaborate, to have the sense of belonging. Thanks to my MidWestern family links, that is already in place, but over the past six years, I have built a very happy relationship with the family of this University, which has a wonderful, and not-altogether-common place within the community where it resides and serves. This is not an academy which turns its back on what is around it – any event that you do, be it a concert, a talk, a

With some of my audience after my first talk at URWF October 16 2023

workshop, or a rehearsal, will be filled with locals, as both enthusiastic audience and participants. So it was, on this trip, from the get-go. I began with a talk on collaboration, composing and human connections on the stage of the marvellous concert hall, to a thoughtful group of teachers, students, locals and visiting musicians from Norway.

This was an opportunity to tell stories of collaboration, and to my surprise, I found that I was talking extensively about the wonder of working with dear Louis Krasner, and most particularly about how my collaborative work with composers, in the three decades since we worked together, has been, in many ways, a mirroring of the process he described of what we might now call ‘workshopping’ with Alban Berg as the violin concerto which he commissioned and inspired. You can find more about this here LINK

On the following day, I began work with a wonderful pianist Ivan Konev, with whom I would play some of the wonderful cycle-travelogue, which the American composer Gregory Fritze, wrote for me in 2020 ‘Spanish Meditations and Dances’. The plan for the concert which gave on my last day at URWF was to frame this with works by Gloria Coates and Michael Alec Rose (also American collaborators of mine) – but, as noted above the sudden arrival of the new work from David Hackbridge Johnson’s new work, would further enhance this programme.

Meanwhile, the Midwestern Autumn was becoming ever more beautiful – along with the challenge how its texture and colour

Back on the dirt road

Somewhere between Prescott & the Twin Cities – 20 10 23

could enrich and challenge my work with bow and pencil. By the end of the week, the colours of the Sugar Maples and Oaks of the woods on either side of the Saint Croix river, was absolutely blazing, a reminder that the greatest challenge of the natural world, which is fundamental to Knowledge Exchange Violin, is perhaps the artistic one.

On the Thursday night, I played in the middle of an orchestral wind concert at the Abbott Concert Hall in the Kleinpell Fine Arts Building. I took the opportunity to return to my ‘opening the composers’ workshop’ roots, and played the first substantial solo piece that Nigel Clarke wrote me, for my 30th birthday concert in 1996. I have performed this piece hundreds of times since, and feel strongly that its success (it always brings the house down, or in this case, a large audience to their feet), is grounded in the fact that the composer and I fought our way to every note, every timbre. Here it is, live, onstage in Nashville, over ten years ago. There are (I know, because I made them) three commercial recordings of this great piece.

Stillwater Minnesota, is one of my favourite places in the USA, and the Rivertown Inn, one of the historic homes in this Victorian lumber town

One of my favourite concert venues – the Riverside Inn, Stillwater MN

on the the St Croix, is a place that I have given many happy salon performances in the recent years. The feeling of the relationship to nature, the blazing Sugar Maples and the River, made if a truly great place to return to my nature themes. So on Tuesday evening, I returned with a programme which had a dialogue with the concert I gave at the Olive Grove, Cyprus, just a couple of weeks back. As ever, the audience was very engaged, and there is such inspiration to be found in this wonderful space.

More and more, I am moved by the response of listeners hearing Olivier Messiaen’s bird transcriptions for the first time. This evening, I played an extended version of his Merle Noir (Blackbird), and there was delighted conversation afterwards, both astonished at the sophistication of what this oh-so-common bird does, but also at the fact, that we all recognise it. The brilliance and virtuosity of birdsong is a quotidian presence in all our lives.

It is very important for me to say that one of the people who makes my adventures in the Saint Croix Valley possible is Kris Tornehoj. Chris is

Very happy collaboration. Working with the wonderful Ivan Konev before our concert of Gregory Fritze, Michael Alec Rose, David Hackbridge Johnson and Gloria Coates University of Wisconsin–River Falls Thanks to Kris Tjornehoj for the photo and everything else!!!!

an inspired educator and friend to her students, and a veritable Pied Piper for the musical life in on the Minnesota-Wisconsin borderlands. I am profoundly grateful for all that she does. Kris is a believer in, and a practitioner of, lifelong learning. Her energy and enthusiasm to enrich the lives of others is uplifting, and time spent in the environments she fosters, always rewarding. She has really encouraged her students and colleagues to embrace the ideas and ideals of my little project – and, consequently made it so much better.

My last event at UWRF was a lunchtime concert of works written for me, in collaboration with the remarkable pianist Ivan Konev. This consisted of the whole of the Gloria Coates Solo Sonata, solo works by Michael Alec Rose (written for ‘Knowledge Exchange Violin’, David Hackbridge Johnson’s ‘River Falls’ piece (see above) and selections from Gregory Fritze’s extraordinary ‘Spanish Meditations and Dances’, cycle, which I recorded with Roderick Chadwick in 2021, and released on Metier last year. This was a first opportunity to play some of this brilliant ‘musical travelogue’ in public: it was Kris Tornehoj who introduced me to Fritze, so so great to bring the material to the place where the collaboration was born. The central plank to everything that I do, after all, is collaboration – other people: anything of quality or use that I am able to do is because of the kindness, cooperation, creativity and voices of others. In amongst the mess that we humans make of our politics, of our planet, or great achievement, which still ranks as great achievement, the essence of what we have come to call ‘culture’ is our ability to work together, to support each other, to love each other.

The great anthropologist Margaret Mead was asked to give an example of the the first evidence of civilization: her interlocuter clearly expected that she would answer with agriculture, tool-making, or cave painting. But her answer was brilliant: Mead gave the example of a human thigh bone with a healed break which had been found in a dig of a an archaeological site dating back the the melting of the ices after the last Ice Age. She noted that, for the person with the broken leg to survive, they had to have been cared for long enough for the femur bone to heal. Others must have provided shelter, protection, food and drink over an extended period of time for the healing to be complete. She showed that the indication of human civilization is care over time for someone in need, evidenced through a fractured thigh bone that healed. I would add, that this is also evidence of another vital quality: love.

Here’s one of the tremendous Fritze movements which we played in River Falls.

With that, it was time for me to leave Wisconsin. In the five days since I arrived, Fall really started to roar in the Midwest, and by the time I found my way back to the Twin Cities, to Old Saint Paul, I was overwhelmed by the beauty and colours of the Sugar Maples and Oaks around me. Here’s the Wisconsin premier of Gloria Coates’ wonderful Sonata – I was so honoured to bring her back to her home state.

Wherever I go, it seems, I am overwhelmed with the kindness and welcome that my various families offer me. Returning to old St Paul, to the elegant Victorian architecture and gardens of Summit Avenue, on the bluff over the great turn in the Mississippi, I found my way back to the home of the writer Patricia Hampl. Patricia is not only family, but as the Los Angeles Times puts it, “the queen of memoir”. For both Malene and I, she is a vital person to exchange ideas with, to talk with, to learn from. We had a couple of days together, before I left for the East Coast, and this was a great opportunity to recharge the batteries, and to take advantage of glorious weather to spend time outside in the full brilliance of the Minnesota Autumn.

Sculpture by Louise Nevelson at the Minnesota Landscape Aboretum October 2023

Patricia took me to the University of Minnesota’s ‘Minnesota Landscape Aboretum’, which offered another opportunity to consider theMinnesota Landscape Arboretum dialogues between nature and art, and echoed, and counterpointed, ideas which were still bubbling up from our time with composer Jim Aitchison at Tremenheere (see above). The gardens include a notable collection of sculpture, distinguished, in my opinion by a number of works by two artists who have been a signal influence on me, and on composers with whom I have worked, or to I am dedicated: Barbara Hepworth and Louise Nevelson.

Naturally enough, it is interesting, even challenging, to witness major works by Hepworth away from the predominantly British environments in which I am accustomed to seeing them. In this way, it reminded me that all art, like, in the long run, all humans, are transplanted, migratory, finding itself, themselves, intermittently, constantly, in the long or short terms, in places which seem, are, unfamiliar, alien. In this way, we are all, to a greater or lesser degree, invasive species. And it is the new arrivals, be they flora or fauna, people or ideas, which in the long run, redefine the landscape, of ideas or in physical actuality. That which was originally alien comes to define home: some of my Huguenot ancestors fled France after the massacre of 1574, and would come to define my native East End (and me), just as much as the Indian food on which I grew up does.

Victorian boilerhouse behind Patricia Hampl’s house on Laurel Avenue, Saint Paul. October 2023

The work of Nevelson took me back to the inspiration of my dear friends, composer and artist, Elliott and Deedee. They both revered Nevelson, who had a similar background to them (she fled as a young girl from the pre-World War 1 pogroms of Tsarist Russia). Elliott’s last quartet, which we premiered in the UK shortly before his death in 2016, was inspired by the storied abstraction of her sculptures. Finding her powerful pieces in the brilliance of a Minnesota autumn morning, reminded me of them both, and that, the reason that I would be moving on to Washington next, was that the very first time I played at the Library of Congress, it was playing Elliott’s music. Elliott and Deedee have left us, but their legacy in my life, continues.

Patricia Hampl has a particular, gardener’s eye and sensibility to nature. Perhaps this was inevitable, as she was the daughter of a florist (and one of her books is called ‘The Florist’s Daughter’). Here’s an extract from what she wrote to me after I left:

‘I’m really glad you were here before MInnesota decided to get wintry before Nov 1–it was 28F when I woke. “High” will be 35. OK, we’re in for the count. I was thinking, looking out at the still glorious crab apple tree my darling Stan planted over 30 years ago, leaves golden, the “berries” (those can’t be called apples, even crab apples) rich red, the dear little space put to bed, all bulbs in the earth with their spring promise, covered with compost and chicken wire (out out, damn squirrels!) that I love the garden at least as much when it is done for the year as when it’s in full flower and fancy pants. I think it’s a bit like putting a beloved child to bed, tucked in nicely and safely. I don’t regret we have these seasons, violent as they can be, and demanding. ‘ Patricia Hampl – Text to PSS 5 11 23?

?

And then, all of a sudden, it was time to leave for DC. I hopped into my hire car, and drove over the Mississippi at Fort Snelling, with all of its tragic history, and was on the plane east….

Washington DC 23rd -24th October 2023

The end of two fantastic days – with my wonderful team at Library of Congress totally inspired by astonishing violins, bows, music, and collaboration – with Carol Lynn Ward-Bamford, Chaeli Cantwell, Clay Penk

So here’s what we did:Filmed on BOTH instruments – with introductions

- Tomasso Vitali – D minor Prelude

- Giuseppe Torelli – E minor Prelude

- Giuseppe Torelli – C minor Prelude

- Ambrogio Lonati – D minor Prelude

- Nicola Matteis – C minor Prelude

- Heinrich Biber – Mystery Sonata XVI ‘Der Schutzengel als Begleiter des Menschen’

- Michael Alec Rose – ‘Philia’

- Michael Alec Rose – ‘The Eclipse of Hipparchus’

Workshop with Michael Alec Rose on ‘Philia’ (Amati)

Workshop with Michael Alec Rose on ‘Hipparchus’ (Stradivari)

Discussion with Carol Lynn Ward Bamford (Curator) about the instruments

So welled up in the course of these performances, discussion and explorations. I think that the most moving thing or me was having the chance to talk with Carol Lynn on camera about the wonderful endeavour of ‘returning’ the ‘Brookings’ to the early set up. I would hesitate to say original condition, for the simple reason that this was not done: in order to make the instrument as useful, as flexible for today’s use as possible, it is in what one might describe as ‘late baroque’, and much will be gained and learnt from playing it with an early classical bow. Indeed, I filmed on it using three completely different bow lengths and designs – a very short ‘Biber’ type bow, the longer, heavier Tartini model and the ‘modern’ stick, which of course is fundamentally a late 18th century form. The violin revealed more and more with each bow.

Tools of the trade. Violins, bows, music, necks and notebooks at the Library of Congress 24th October 2023

In the course of this two extraordinarily intense days of music and discovery, I had a moment of clarity. It suddenly struck me, that in addition to playing each piece on two different instruments with different setups and different bows, something else was happening. This something else was all the more clear as I was doing two full takes of each piece, so every work was getting four performances: and none of these performances had anything in common with each other. Now, I have to be clear about something here – I am not very interested or excited about musicians and their interpretations, but I am very interested in what happens when a piece is played. And what struck me most forcibly about this particular journey, was that these living, organic violins (and bows) were showing me different paths, different tracks, each time.

I started to wonder why this might be, and can only suggest this: perhaps this might have something to do with the histories, the stories, that the instruments and their materials embody, and record. Take the front of any violin, and look past the many stories of its making (the carving, marquetry, ground and varnish) and its use (the patina, abrasions, scratches and rubbings). Just look at the grain of the maple itself. I

Spruce, close up, from the front of a violin by Girolamo Amati 1629

will just go to my violin case and take a photo: So here it is – the front of a violin made by Girolamo Amati (1562-1630) in the year that he died. So this is a lovely piece of pine, representing (in the photo) about 25 years of growth. Of course, the plank has been cut as a radius of the trunk, in order to get the most even grain.The rings consist two elements early or spring wood) and late wood or summer wood. The ‘early wood reveals the most active period of growth in the annual cycle, and is less dense, with large cells with thin walls. Going through the year, growth slows, the and the cells smaller and denser, this is late wood, darker than early wood having more concentration of cellulose. Naturally, meteorological and ground conditions mean the no annual ring is the same as another – they can also reveal periods of high hind (putting strain on a tree), or even storm activity, a certain ripple in the wood which carpenters and violin makers call a ‘thundershake’. And it’s important to remember what is concentrated in the darkest parts of the rings, veins running vertically along the tree (or, here, horizontally), which enable the action of photosynthesis in the leaf canopy to dray water up through the tree. The many hundreds of rings to be found in the 84 pieces of wood that make up a violin all tell incredibly detailed stories of the years of their growing. Conservatively, I would say that this piece of wood, which would have been taken from the heartwood of a tree which might have been cut down when it was let’s say, 150 years old, is a narrative of the early-1500s, the age of Luther, Henry VIII and Colonna.

My feeling, which increased in conviction this week, is that the act of setting wood in motion, might be akin to a revival of these arboreal chronicles. Perhaps I should not be surprised, that it leads me down paths unknown unsuspected, when I play a great violin, let it, and its material, show me new, or very old tales.

It is fair to say that playing and listening to the two violins, one after the other, playing the same material, did not invite any comparison between the relative virtues of either the instruments or their set-ups. In fact the only time that this came up was with regard to fingerboard length – one moment in one of Michael Alec Rose’s pieces demanded a leap up the A and E strings which was right off the end of the baroque fingerboard of the Brookings, but within the compass of the Ward. Curiously, and we all felt that this was the case, the result was that the ‘baroque’ version had a fleshy, human result, whilst the modern setup of the other resulted in a more intellectual outcome. We started to talk about the instruments as having, respectively, Apollonian or Dionysian qualities. And no artists would wish, or dare, that either of these was inferior: both are equally vital.

Here is what Michael Alec Rose wrote about this experience:

Peter Sheppard Skærved has a way of bringing out the best in everybody and everything, thanks to the faith he places in the collaborative process. On October 23-24, 2023, I was privileged to bear witness to the culmination of his collaboration with the brilliant curator Carol Lynn Ward-Bamford at the Library of Congress. This adventure is one beautiful facet of Peter’s long-term international project, Knowledge Exchange Violin. It was my second visit to the Library in the past year, my second chance to hear Peter work in the Whittall Pavilion, hard by the Coolidge Auditorium, exploring—with the amazingly knowledgeable help and expertise of Carol Lynn—the infinitely rich sonic resources of two magnificent violins. Recorded on film, Peter introduced and played music from the era in which the instruments were made, and also the new music I had composed for them. My compositions are short; but if they asked me, I could write a book about the twofold experience—two visits, two collaborators, two instruments, two pieces—of seeing and hearing my music come into being, embodied in dramatically divergent ways on the Ward Stradivari and the Brookings Amati. The pieces are called “Philia” and “The “Eclipse of Hipparchus”, titles which reflect my sense of wonder about how these glorious violins have been preserved, just as so many historic documents and artifacts have been assured a miraculous immortality in the Library of Congress. On this site at the vortex of the present moment’s political and civil fragility, right atop Capitol Hill, Peter’s and Carol Lynn’s shared vision of enduring musical value and profoundest beauty was captured by a film crew who were visibly awed by the great violinist’s playing and inspired by the long tradition he was making vividly audible on the Strad and the Amati. It is an honor beyond measure for me now to be part of that history.

The Madison Building, Library of Congress, 23rd October 2023

And then it was on to New York City. I was able to finish filming at the Library and then wheel my suitcase down the hill to Union Station to get the NE Regional along a route I have travelled so many times – through Baltimore, Philadelphia ( with memories of George Rochberg), past the famous bridge at Trenton (‘Trenton Makes, the World Takes’) and back to Penn Station, and the Subway uptown: back to Central Park West, where my father-in-law, Garrison was waiting, with conversation and coffee.

New York City 25th October

With Bradley Strauchen Scherer and the film team at the Metropolitan Museum (holding violas by Benjamin Banks and Robert Horne) 25 10 23

Here’s what we filmed in one day!

The exciting thing with both these institutions, is that the projects have steered themselves, each following particular threads. Since the last set of films at the Met (Viola d’Amore etc), they encouraged me down a fascinating path of 18th and 19th century lutherie in the US. This resulted in our discovery, in the collection, of the oldest true American-made violin (that survives) made by Robert Horne on Pearl Street New York in 1757 (beating the previous record by two years). So I filmed on six instruments – beginning with repertoire that I filmed on their 1693 baroque setup Strad 1693 last time, but this time on the matched instrument which is in modern, all the way up to two astonishing Gemunder violins (New York maker – pupil of Vuillaume) from the 1890s. Michael Rose wrote a wonderful piece for the New York viola, continuing his blue streak of pieces for instruments and ideas around Knowledge Exchange.

Here’s the menu:

Works recorded – Metropolitan Museum 25th October 2023

With the ‘Francesca’ Stradivari 1693 during filming at the Metropolitan Museum 25th October

Francesca Stradivari 1693 & Stephen Bristow bow 1981

- Henry Eccles – A minor Prelude (publ. 1700)

- Nicola Matteis – G minor Prelude & D minor Sarabande 1790

- Johan Joseph Vilsmayr – G 1886minor Partia (Harpeggio & Gavotte) Scordatura GDAD 1710

Charles Francis Albert, Sr. – Violin 1886 with Voirin bow ‘Dushkin’

- Richard Strauss – Daphne Etude

- Ole Bull – Sæterjentens Sondag

- Carl Nielsen – Børnene Leger

August Martin Gemünder – Violin 1893

- Joseph Joachim – Schottische Melodie

- Kreutzer – G minor Caprice No 23

- Gloria Coates – Berceuse

August Martin Gemünder – Violin 1893

- Julius Rontgen – Air

- Mylarguten/transcribed Halvorsen – Gangar (Scordatura Adae)

- Kreutzer – A minor Caprice No 1

Robert Horne – Viola 1757

- John Playford -‘The Princess’ ca.1670

- Karl Friedrick Abel – Adagio (37 pieces)(Scordatura DGDA)

- Michael Alec Rose – Horne Call 2023

Benjamin Banks – Viola 1791 with ‘Kew’ Dodd bow ca. 1800

- Pierre Baillot – Chant des Litanies & Air Ancien

- David Hackbridge Johnson – Verset 1 2020

- Giuseppe Tartini – Andante cantabile

- Michael Alec Rose – Horne Call 2023

There’s something amazing that happens, when you have to play an unfamiliar violin or viola, on camera. There are, in my way of thinking, only two ways of approaching a ‘new’ (ie unfamiliar instrument). There’s a right way and a wrong way. The wrong way, which I am afraid, a lot of us a guilty of, especially when picking up a ‘great’ violin, is to impose on the instrument, to demand that it produce a certain glamourous, burnished, voice, that reflects our sense of pride at having the fiddle in the hands. And there’s the other approach, which is to allow the instrument to come to us, to let it sing, speak and ring unimpeded. That method certainly helped with the challenge of this days recording – only one instrument which I knew well, and the rest, wonderful voices that began to dance and sing delightfully in the course of the day’s filming.

I think that, without doubt THE revelation, and one which was felt by the whole team, was the Charles Francis Albert, Sr. 1886 violin, which I

Musicians in the Wheaton High School Orchestra, ca. 1890 (DuPage County Museum)

played with Samuel Dushkin’s Voirin bow. Because this violin has for so long been labelled, shelved and to a degree, tabled, along with many other ‘mute’, or ‘quiet’ violins as a practice instrument, it’s meaning and charm was long forgotten. A few days later in Wheaton, Illinois, I would find myself looking at musicians from the same period, who would have appreciated its delicacy.

Here they are, some of the young women and men who made up the high school orchestra of what was then Wheaton, then quite separate from Chicago, before it was subsume in that city’s suburban sprawl. Look at the fabrics of the dresses, the razor sharp collar and coffs, the care and love for the instruments. I do not know that any of these people became professional musicians, although perhaps the men found their way into what would become the Chicago Symphony. However, there’s no denying that, even looking at this picture in the Dupage County Museum, I could see people who took local, domestic, salon music making, very seriously. And the late 19th century salon in middle class America was one of gentle manners, thick fabrics and heavily moulded carvings on dark-varnished furniture, with tables

Playing the Charles Francis Albert, Sr. – Violin 1886 with Voirin bow ‘Dushkin

laden with ferns. This, and the restrictions of every more crowded cities, demanded instruments to match, and I would suggest that the unique, and beautiful Albert violin, fitted that need.

But to go back, just a little, one of the tasks attendant on this day of filming was related one of the instruments that I filmed on this time last year – the ‘Gould’ Stradivari. That instrument is in ‘baroque’ set-up, having been converted ‘back’ in Amsterdam in the 1970s. The ‘Francesca’ Strad in the collection is an almost identical instrument. Both are ‘long-pattern’ instruments, and were made within a year of each other. However, the ‘Francesca’ is in ‘modern set-up. So the team at the Met asked if I re-record the pieces which I filmed on the ‘Gould’ (baroque) on this instrument: it’s worth noting that was doing, albeit at a year’s distance, what I had done at the beginning of the week on the ‘Brookings’ and ‘Ward’ instruments at the Library of Congress. Of course, the real shock, and it was a shock for which I should have been prepared, was what it felt like reversing from a ‘Golden Period’ Stradivari to a ‘Long-Pattern’. It might be said that there was as much differences to be found and felt between these two conceptions of the violin, less than 10 years apart, as between the early and modern state instruments.

Now it’s on to Ithaca College, then Wheaton (Chicago), and then Peaboday (Baltimore) to give more concerts and presentations about the project, before returning to the Twin Cities to film with Ole Bull materials and instrument at the wonderful collection of the Schubert Club Museum in St Paul.

26th – 29th October – New York City, Ithaca, Norwich Connecticut

28th October Afternoon by Buttermilk Falls

With Evis Sammoutis