A seven-month project, funded by Research England June – December 2022.

In case you’re in need of a pick-me-up. ?

Violinist Peter Sheppard Skaerved (@Sheppardskaerve) stopped by the museum today to give our visitors a surprise performance. ? pic.twitter.com/rEjgfz34Bq

— National Gallery of Art (@ngadc) July 7, 2022

Playing/talking. Full Circle, Brussels. 9 6 22

With thanks to the Royal Academy of Music

Knowledge Exchange Violin is an eight month project with institutions and collaborators on both sides of the Atlantic. It is an open-ended exploration, violin in hand, of questions, ideas, and possibilities that emerge from the shared creative and questing process. The ‘big picture’ is the natural world, and our place (or not) in it. And the small focus, the soul the journey is the violin, in action, being made, bow on string, an idea and machine, whose usefulness seems to trascend eras and epochs.

Collaborating Institutions

National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Library of Congress, Washington DC

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

Schubert Club Museum, St Paul

Cyprus Archelogical Museum, Nicosia

Full Circle, Brussels

University of Wisconsin River Falls

DAY by DAY – the project unfolds -(Blog reads from top to bottom-scroll down for most recent)

Environment: a moment at RSPB Farham Heath

Day one – 3rd June 2022-643 Euston – Oxenholme

The train pulls out of Euston Station on time, and our carriage is empty. This is a familiar point of departure, but today, something very different in the air. The project begins here. Malene Skaerved and I are en route to RSPB Leighton Moss, one of two reservers which are fundamental to my project.

There have been many conversations over the past few months, as ‘Knowledge Exchange Violin’ started to come into focus, with my collaborators on this project. The recurring theme, is that all that we know about the project, is that it will find its themes, its motifs, in the doing. Talking with one of my colleagues from the USA, she observed: ‘I have never seen you like this: usually you know exactly what you are going to do … this is different. And that is a good thing.’

So the best way to explain what it is that I am doing, is to introduce the themes and materials. These will shift and change, but this is where we start:

- The storytelling violin. Workshops, collaborations, meetings, history

- Migration, travel, emigration, exile, encounters

- Music in the landscape. Environment, ecology, birdsong,

- Music and visual art, from representation to inspiration, ideals.

- The workshop; composers to luthiers,

- The revolutionary salon; art and ideas, music and politics

There will be films, concerts, recordings, articles, salons, podcasts, and much more, developing my collaborations with institutions on both sides of the Atlantic. One of the hearts of the project, is the idea of the instruments made by the Amati family.

Violin by Girolamo Amati

Cremona 1629 (2nd June 2022)

I will bring two aspects of these instruments that I love, which are key to this project: First of all, their ‘framing’ of natural beauty. It’s impossible to look at the back of this amazing violin, by the generation of this central family of violin-making without noticing, that the first quality which the instrument celebrates, if you will forgive me, is the astonishing wood from which it has been made. The beauty of that wood, of course, rests in its relationship with the environment in which it grew, from the season ebb and flow of tree rings, to the marks of time, the unpredictable, both in its growing and in its wear since it was cut down. I will explore this idea in depth as the project develops. The natural world, and its dialogue with time-passing, is fundamental to a musical instrument like this. The second quality of the Amati instruments, is a more domestic, even homespun one: the sense that from parent to child, these instruments were the product of a family; three, four generations of idealised craftsmanship, of art, within a home environment, and perhaps the sense that this quality is tangible, audible in the instruments.

South of Crewe. Flying north. 3 6 22

But today, we are en route to the Northwest coast, to Morecambe Bay. Malene is with me, as she will be directing the films which we are planning to make working with the two RSPB reserves we are planning to celebrate. We will meet up with the celebrated nature writer, Laurence Rose and composer Edward Cowie, whose extraordinary music, is as he often puts it, a ‘habitat’. It’s just the first step, exploring the extraordinary geography and ecology of the Cumbrian coast, allowing the dialogue between art and environment to emerge, with no agenda. Lets see what happens.

Leighton Moss RSPB 3 6 22

2300 – same day: a day of conversation, ideas, and inspiration. This picture is what it is all about. This is Leighton Moss seen from the observation tower on the Northwest side of the reserve. Immediately that we climbed up, we were greeted by the sight of three Bitterns and a Marsch Harrier. An auspicious beginning for the day, and the project. I will write more about it tomorrow from the train.

Day Two – Cumbria to London, thinking about yesterday

The first important activity was to bring together the core team for this project. After lunch with Edward, Laurence, and artist Heather Cowie, we went over to Carnforth, to meet up John Carter, the ‘Visitor Experience Manager’ for Leighton Moss Reserve. A fascinating conversation began, on the top of the ‘Skytower’ observation post overlooking the moss.

Themes emerged – overlayering ideas of change and scale, from Tide to Historic Inundations. Migration Eels in their hundreds of thousands, birds, Hen Harriers finding their way to Africa, Mesolithic travellers settling on the Highwater mark, the Norwegian Vikings arriving from Ireland in in 1901… but one overriding them – the relationship between the historic necessity of change ( a reed bed should silt up, become a fertile wooded valley, the wetland moving somewhere else on the coast), balanced with the question of the question of conservation, which by definition, means perserving, artificially this environment, in situ. This idea will mature, develop, and seems to be fundamental to my larger project.

Skytower Conversation – RSPB Leighton Moss – Laurenc Rose, PSS, Heather Cowie, John Carter, Edward Cowie. Photo Malene Skaerved 2 6 22

One of the most remarkable things about the conversation, was that it took place in a most wonderful counterpoint with nature. Whilst the excited talk, all ideas and possibilities, was barreling along, the wildlife mounted a spectacular display. Three Bitterns, wrose from the reed beds, and swept to and from over the Moss. I had never seen one of these extraordinary, booming waders before, and had never thought what they would look like in flight. At the same moment, a yellow-headed female Hen Harrier hovered over her nest site, almost directly beneath the observation tower: conversation turned to the feeding/display flights of these birds. I was, embarrassed to admint that I had no idea that these birds were so large, as big as the Red Kites I know so well from the Chalk hills of the south, but more muscular, energetic.

One of the most important aspects of my work with the RSPB has been the mantra ‘It’s not only about birds.’ That will be so important here, and perhaps this contrapuntal feeling, ideas finding their way in and around the screaming chit-chat of acrobatic gulls, the wonder of a droplet of water poised on a bulrush rlflecting the myriad colours of an ever-changing sky, is a model for the music, the art, the writing, the film, which will emerge from the project (large and small). I will return to these themes.

Geology, and botany in action, The Cove, Silverdale, 3 6 22

The next stage of the day of discovery and ideas was Hest Bank, just north of the town of Morecamb, and then The Cove , Silverdale. There are many binary aspects to this landscape. Perhaps the most powerful of them, is – Fresh- or ‘Salt – water’. The wetlands of Leighton Moss are protected from the tides of Morecambe bay by manmade sea defences.

A moment to think. Hest Bank, Morecambe Bay (Photo Malene Skaerved) 3 6 22

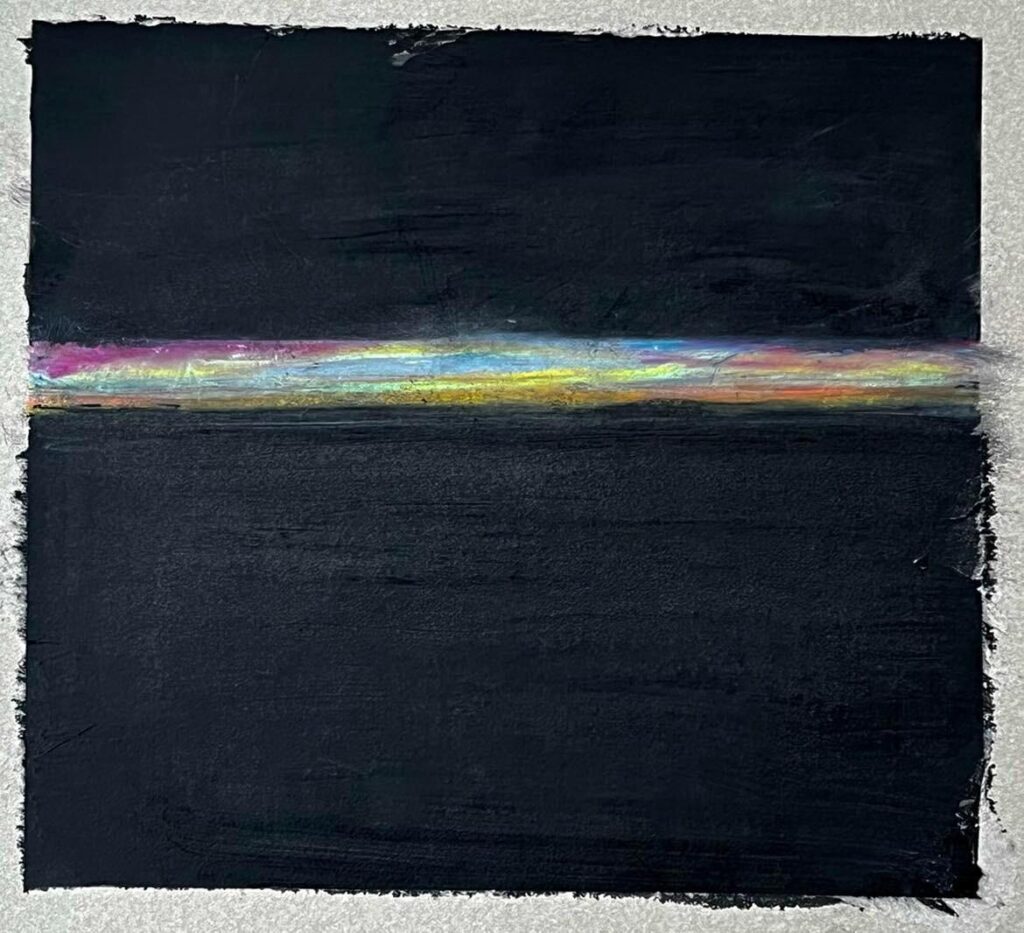

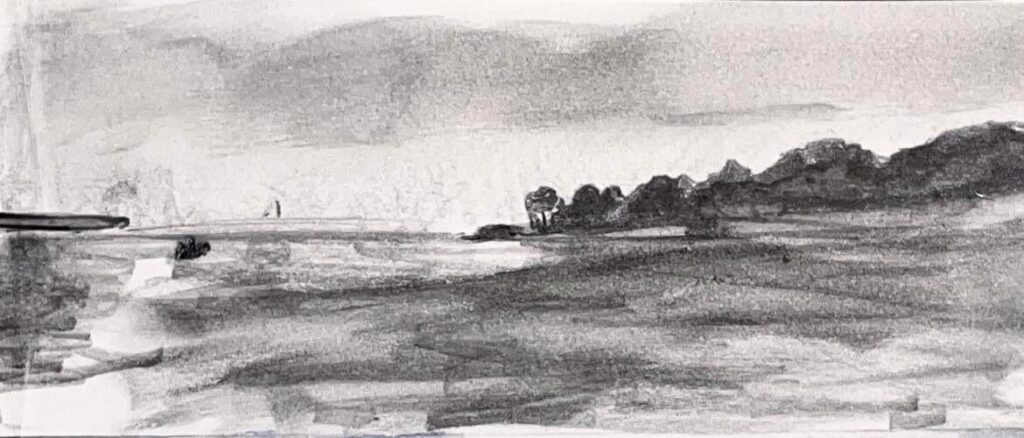

Standing on the rocky beach at Silverdale, we wer lookig across the tidal wonder of the bay, and at the highwater mark, there’s a sense of the liminal nature of this littoral environment. Heather Cowie and got down into the mud, and explored the constant erosion and sedementation, and the spectacular intersect between plantlife – from seaweed, throught to saltwater-tolerant Samphire and Sea Thrift. For both Heather and I, as artists, the sense of horizon is so important. Talking about her paintings the next day, Malene noticed that, however far they evoke landscape there is an evermorphing fascinating with point of view – be it from head height, ground-level or from beneath the water. Heather’s most recent cycle of paintings is particularly associated with this environment, so her sense proved so inspiring, on the ground.

New work by Heather Cowie- much of it inspired by Morecambe Bay 4 6 22

From wetland, to shoreline, to tidal estuary. The last stop to watch and think was at by the River Kent at Arnside. The tide was on the ebb now, and perhaps this was the place that feels most like home. Whilst Malene and I are city dwellers, we live right next to the Thames at its most dramatically tidal. Ebb and flow, the effect of the tide on the our environment, is our everyday, and I suspect, that it will offer another layer of dialogue for this project.

Larger narratives: Clouds and mountains over Patterdale and Ambleside, looking from the bank of the River Kent 3 6 22

Day 3 – Sunday June 5th 2022 Wapping

Today I had to turn my attention to the programme that I will be playing this week on two Amati violins from 1572 and 1529 in Brussels, an an upcoming conversation at the famous Musical Instrument Museum (MIM) in the Belgian capital. The programme ‘The Violin Begins’ stretches from the earliest solo works for the instrument, from the 1580s to 1710, a decade before the great solo works of JS Bach. Here it is:

Giovanni Bassano (ca. 1550-1617) Ricercata Ottava (Ricercata/Passagi et Cadentie 1585)

Biaggio Marini (1594-1663) Sonata per il violin solo semplice & Capriccio per sonare il violino con tre corde à modo di Lira (Pub.1618)

Thomas Baltzar (1630-1663) Four Tunings (Scordatura AEac#)

Nicola Matteis (fl. c. 1670 – 1717?) G Major Prelude (1676)

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber (1644-1704) D Major Rosenkranz-Sonate ‘Auffindung im Tempel’(Scordatura Adad) (ca. 1680)

Le Sieur de Machy (fl. 1655–1700) Menuet, Courante et Double (Pièces de Violle en Musique et en Tablature) (Publ. 1685)

Anonymous/Klagenfurt MS (ca.1685) G Minor Suite (Scordatura GDad)

Giuseppe Torelli (1658 – 1709) E minor Prelude (Publ. 1700)

Johann Joseph Vilsmayr G minor Partia (‘Artificiosus Concentus pro Camera’) (Scordatura GDad) (Publ. 1715)

Balancing these pieces, works written for me by composers during the 2020-2021 Lockdowns.

All sorts of typologies are playing themselves out in my head, between the old works and the very new, between the forms of instruments and the forms of pieces, between the forms of the natural world and the forms of all of mankind’s creations. Naturally enough the extraordinary impact of the past two days in Cumbria is still making itself felt – I found myself recording two of the earliest composers on this programme with images from two vantages by Morecambe Bay in mind.

At the back of my mind, an observation made by composer Edward Cowie, who occupies a unique vantage point as both a musical creator of genius, as well as a scientist, artist and writer. He is always, a veritable fountain of ideas. When we sat down for the first conversations at his home at Fell End, Cumbria on Friday, he immediately said:

‘Lets think about insects as the inventors of instruments. It is clear that there is a direct link between the ectoskeletal inverterbrates-their means of making noise, both with the chambers of their bodies, and, quite literally, ‘playing’ the body – think of the grasshopper scratching it’s wing edges with the serrated back legs – bow and string – and the invention of string instruments – both of them carapaces.

Immediately the conversation swung into the classical greek notion of Orpheus using the tortoise shell to make the lyre, and then the fact that native-american instruments not only imitate the sound of the animals, but also their appearance. It’s not a huge leap to see that the side view of a violin, is linked to that of a tortoise or terrapin – and not surprising that in pre-CITES days, tortoiseshell was so sought-after in the decoration of instruments, and in a number of cases, their complete manufacture.

An Andrea Amati violin, like the one I am playing in Belgium on Friday, stands at the moment that the instrument emerged into unity, that all these ideas crystallised, perfectly, for the first time, into an instrument that would not need fundamental change for, so far, nearly half a millenium. The exploration of these links, between the symbolism and sound of the instrument, and the natural world which not only to they imitate, but which provide the precious materials for their manufacture and maintenance, is, clearly at the heart of Knowledge Exchange Violin!

Memory: Strange Light on the horizon/when at sea 6 6 22

Tomorrow, I turn to the Revolutionary French aspect of this project: this links specifically to two institutions: the world’s oldest museum – the Ashmolean in Oxford, and the great Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota. What, you might ask, are the links to the themes emerging from your project. To which I offer this-all will be made clear:

Monday June 6th 2022 – Revolution: Science & Art

Here is the frontispiece of Volume 1 of ‘Révolution française, ou Analyse complette et impartiale du Moniteur’ 1799. It’s one of my favourite finds, rooting about in junk shops. Volume one is a day by day chronicle of political, diplomatic, social, scientific, literary and artistic events in and around France from 1789-1791.

Dedication: to the body politic, to the sciences, and to the arts frontispiece of Volume 1 of ‘Révolution française, ou Analyse complette et impartiale du Moniteur’ 1799As the engraving that begins this book makes clear, Art and Science were, necessarily, contrapuntal, interdependent. The Cithara on the left, needs the Euclidian and Pythagorean geometry at the right. In every age, political revolutions have engaged with the question of how the sciences and arts should ( or should not) be fundamental to every aspect of life, and with each other. The musicians and artists who were part of the revolutionary age, on whatever side, were fascinated with nature. William Wordsworth was in Paris in 1789, Viotti (a Rousseau-ean idealist chased from France in 1790, but then sought out by the Napoleonic establishment), was the epitome of the Zeitgeist, and found inspiration and ideas, like Stephanie de Genlis, Elisabeth Vigee-le Brun, in the countryside.

And so, my project, which seeks out these links, will reach out to Revolutionary France, through one very particular violin (of which more later), and through my collaboration with the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The Institute has a wonderful collection of Parisian Fashion journals from the 1790s, the ‘Journal de la mode et du goot, ou Amusemens du salon et de la toilette’. These weekly magazines, informed the readers of how to where (and NOT to wear) the fashion of the day (quite literally), and what to play and sing, and how to sing it. Today I begin work on the music (published, alongside the fashion plates), with two great colleagues, the singer Héloïse Bernard, and my long-time collaborator – Keyboardist and musical inventor, Julian Perkins. The recordings will form part of the exhibition which opens in Minneapolis in the Autumn\ More to follow, after our rehearsal.

Later the same day; back from rehearsal in Julian Perkins’ harpsichord room at home in East Dulwich. Upon arrival, there was a rather abrupt switch into Italian. Julian’s in-laws were over from Italy, and I found myself lurching into a conversation about ‘il tempo terribile Inglese’ with this delightful couple. Thank goodness, Julian handed an espresso which sped things up: it’s been a while. And then, to work-we will be joined by our soprano for the project, Heloise Bernard, soon (Easyjet had put paid to her plans of joining us from Edinburgh!). But today was a chance to establish some parameters for how these delightful pieces, perfect little miniatures, will work in our re-imagined salon. The conversations, vital for working on this music, stretched to the cult of nature, the influence of Mozart. and the ever fascinating world of juggling parts and voicings, as well as the joy of elaboration, ornamentation, which is the Julian and my shared fascination. I think, that my favourite of the songs, by an anonymous ‘demoiselle’ was the simplest: ‘Pauvre Jacques’. And the sound of the salons of pre-and post revolutionary France, begins to reemerge.

Concentration: Julian Perkins and I begin work on a wonderful project of 18th Century French music, for Minneapolis Institute of Art. 6 6 22 East Dulwich

This evening, I have been idling my way throught the list of pieces in the Jefferson Family collection ( listed in the back of Helen Cripe’s ‘Thomas Jefferson and Music’ University of Press of Virginia, 1974). The reason was that, in the course of our rehearsal today, Julian Perkins and I had the most powerful impression that Maria Hadfield/Cosway and Thos. Jefferson were the the room, playing and singing the the Sacchini Aria they loved (‘Jour Heureux’). So this evening, I pulled the book down from the shelf, as I felt I should read the list of sheet music: Pp.121-2 ‘Pauvre Jaque’ [sic] …Song with pianoforte accompaniment’ etc. , which led me to Jeanne-Renée de Bombelles Travanet, and the possible source of the words, Marie Antoinette. On the road for the next few days, with Vigee-le Brun’s ‘Souvenirs’.

Tuesday 7th June 2022 London – Bruxelles

I have been thinking more about the intersect between the natural world and the arts overnight. A few weeks ago, I was lying in a field on the Ridgeway, in the Chilten Hills, waiting to record the ‘Chaconne’ by Mihailo Trandavilovski. In the village hall, just down the hill from the grassy bank where I was lying, the great clarinetist Roger Heaton was finishing up his recording of Trandafilovski’s solo piece. It was a perfect warm spring day, and every bird seemed to be singing. The arching phrases and barely-there high clarinet notes found their way, naturally, into the symphony of bird song, and then were joined my the call of a huge Red Kite, hunting in the sky over where I was lying. Fortunately, I was able to record it. Here it is:

June 8th 2022 – Woluwe-Saint-Lambert, Bruxelles

Today, a day to wonder about this marvellous city (in the pouring rain), and to let its themes and ideas find their way in. I am, very much an enthusiast for cities, and there was much to explore, walking with Malene and my long-time collaborator, the composer Nigel Clarke, who lives here. In a day of remarkable things, I was most struck by this.

Pulpit, St Michaels and St Guluda Cathedral, Brussels 9 6 22

This extraordinary pulpit, was carved by Hendrik Frans Verbruggen ( 1654 – 1724) in 1699. It reaches back and forth, from the world of art, philosophy and religion, to the natural world, and its influence (and imitation), which is so central to my project. It also fits into the centre of the concert which I will give tomorrow night here, in Brussels, and the aesthetic, questions which 17th century instruments and instrument-making address. The pulpit depicts, Adam and Eve, fallen from grave, clad in skins, being driven from Eden by the angel with a flaming sword, and, behind Even, who is still holding on to the apple, Death. The structure of the pulpit is the tree of knowledge, and the serpent winds up and around it, to the top over the sounding board. There, it is is trampled by Mary, riding her crescent moon, but referencing the passage from the Revelation of St John:

12 Now a great sign appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a garland of twelve stars. 2 3 And another sign appeared in heaven: behold, a great, fiery red dragon having seven heads and ten horns, and seven diadems on his heads. 4 His tail drew a third of the stars of heaven and threw them to the earth. And the dragon stood before the woman who was ready to give birth, to devour her Child as soon as it was born. 5 She bore a male Child who was to rule all nations with a rod of iron (Revelation, 12, 1-5, King James Bible)

The tree reaches from earth to heaven, like the Yggdrasil, in Viking mythology:

The ash is of all trees the biggest and the best. Its branches spread out over the world and extend across the sky. Three of the tree’s roots support it and extend very, very far. (In Gylfaginning/Prose Edda Chapter 15 Snorri Sturluson)

It is this linking, from heaven to earth, from hight to low, from worldly to the heavenly, from art to nature, which seems to be driving the project. Then back ‘home’ to Woluwe-Saint-Lambert. and practice for tomorrow’s concert.

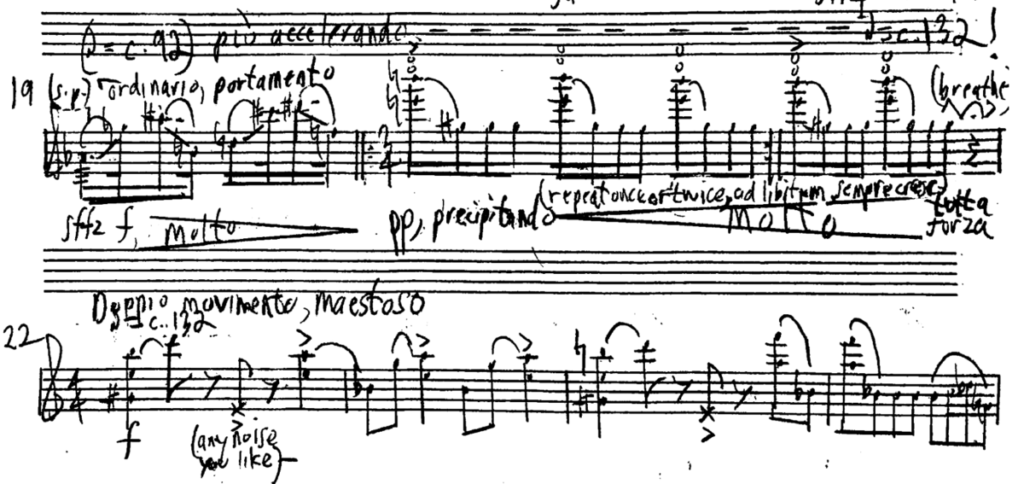

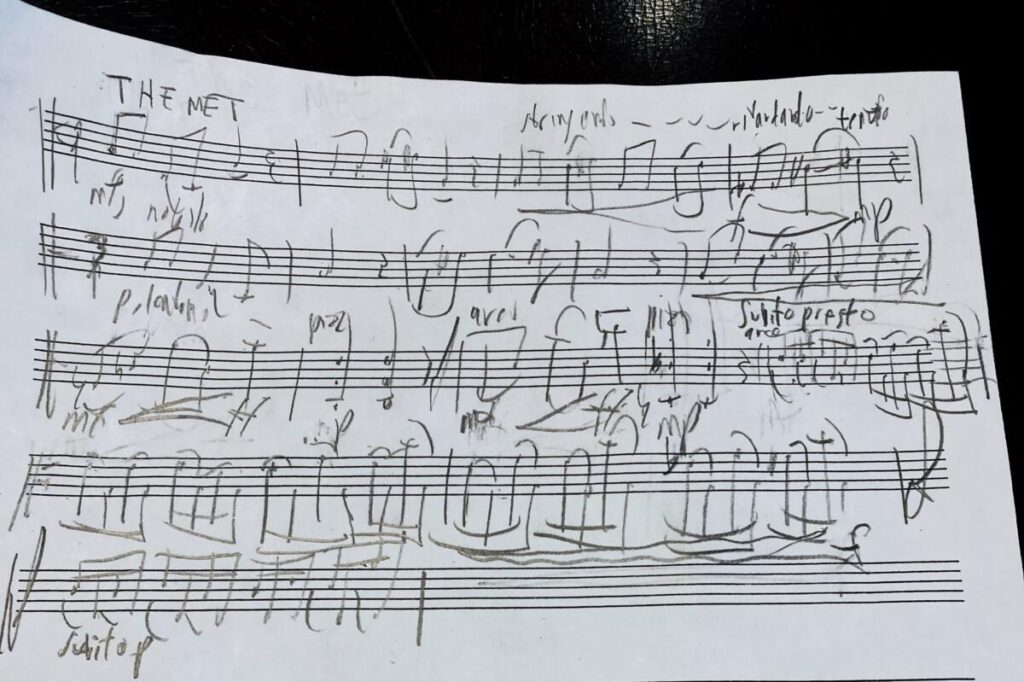

Today’s practice desk. Woluwe-Saint-Lambert, Bruxelles. Tomorrows event – Music from 1580-1700, plus, Sadie Harrison, Mihailo Trandafilovski, Naji Hakim, David Gorton Evis Sammoutis, Hafliði Hallgrímsson. Salon concert tomorrow 8 6 22

Brussels – 9th June 2022

An extraordinary day. It began with a visit to the wonderful Brussels Musical Instrument Museum, where I met with the Anne-Emmanuelle Ceulemans, the Curator of musical instruments, and Joris de Valck, restorer.

Exploring Girolamo Amati with Joris de Valck and Anne Emmanuelle Ceulemans, at MIM Bruxelles, 9 6 22

I am fascinated by different approaches to the presentation of musical instruments in museums. These range, at opposite ends, from the playing collections of the Library of Congress, Washington DC to the silent ones, including the Hill Collection at the Ashmolean Museum and this museum. There is an unfortunate tendency for musicians to be dismissive of collections which they cannot play, as if there is nothing to be learnt, that they offer them nothing. This is clearly nonsense, as was demonstrated today.

I particularly wanted to meet the 1610 ‘Brothers’ Amati violin, which is one of the stars of the collection. This, I hoped would be a recognisable sibling of the the 1629 example which I play (made just before the composer’s death in the catastrophic outbreak of Bubonic Plague in Lombardy 1629-30). As soon as I saw the instruments together, the kinship was obvious, and conversation started to flow, about the qualities of these instruments: what is it that draws us, as players and audiences were drawn from the 1570s onwards, to the instruments made by Andrea, Girolamo and Nicolo Amati?

This most obvious thing, as soon as we saw the two instruments together, is that the wood choice and surviving ground of the front of

he insturments have much in common. As soon as the purfling was compared the same hand became ovious. The exciting differences are to be found in the wood selected and the treatment of respective backs of the instruments. They are both ‘one-piece’ but there there are more differences to be observed. If one was imagining that these two instruments were made, each for sets of instruments kept as treasures in a collection then, I might go as far as saying that each might represent a different passion, a different ‘affect’ even a different humour.

Together Girolamo Amati both. on the ;eft, 1610, on the right, 1629. MIM Bruxelles 9 6 22

So, it is probably a good idea, to answer the question, ‘why Amati’? There are many answers to this question, and those answers raise yet more questions. So I will begin with the most subjective answer. In the near-decade, that my work has focused on the instruments made by the first three generations of this family, I have come to the conclusion, that the reason for my love of their instruments is that the most all-envelopping understanding of the violins made by Andrea, Girolamo and Nicolo, is that they feel and sound, as if the were made in, and celebrate, the atmosphere of the home. That is not to say that there is anything domestic about the instruments, but rather that, unlike (from experience), the overwhelming impression of the work of Antonio Stradivari, epitomised in Dyrden’s ‘Ode to Cecelia’s description of the violin, Amati instruments begin from a fundamentally generous spirit.

Sharp violins proclaimTheir jealous pangs, and desperation,Fury, frantic indignation,Depth of pains and height of passion,

For the fair, disdainful dame. (A Song for St. Cecilia’s Day, 1687 – John Dryden)

Our ever-welcoming host in Brussels has been my dear friend, long-time collaborator, and musical brother, composer Nigel Clarke. We met as undergraduate students at the Academy and evolved a working method, of exploration and adventure, which is, if I am honest, the foundation for projects like this one. We will be recording his latest work for me (our third concerto collaboration), with the Austrian Radio Symphony Orchestra in Vienna this summer. He and his wife, Stella an their inspiring sons, Joshua and Emil, have been our home from home here in Belgium. Having Nigel along at a beginning of a voyage of discovery, like the meeting with the team at the MIM, is always inspiring – he stands back, watches, learns, and then comes up with a brilliant idea, a left-field suggestion, which can, and often does, set a project on fire. The most important thing that we have learnt to do, is a term coined by my friend, the anthropologist, Genevieve Bell: ‘Deep Hanging Out.’ So, perhaps the most important part of the day was sitting at a pavement cave, with coffee and a croissant, with Nigel, talking, and waiting to see what might happen.

Composer Nigel Clarke. Morning 9 6 22, Bruxelles

Funnily enough, the building that we were looking, coffee in hand would find its way into the evening event. It, and the concert, speaks to the question of travelling musicians, music, and instruments across Europe from the end of the Renaissance onwards. Right next to the Museum, stands the Hotel Cleves-Ravenstein, or rather the remains of it- and extraordinary memory of the lost glory of 15th century, and a link, tenuous indeed to the music of the Bassano familly, which began my concert later in the day.

Hotel de Kleve-Ravenstein, BrusseLS 9 6 22

I began the concert/salon at ‘Full Circle’ that evening, with a piece by one of the Venetian Bassano family of instrument makers and composers. Some of them came to London to play at the wedding of Henry VIII to Anne of Cleves, whose family built this home at the end of the 1400s. This theme, of the relationship betwee the travel of music, instruments and musicians, is one of the fundamentals of my explorations.

One of the sitting rooms of Full Circle, which would be filled with conversation after my concert in the theatre there 9 6 22

After the concert, excited conversation began, as so often, around the instruments. There is no musical instrument, and indeed, very few human artefacts, that excite more fascination and excitement than a violin. So often these post-concert discussions are where so much happens. In Brussels, the combination of musicians, writers, violin makers, painters and thinkers made for a particularly inspiring, and for me, even heady brew of ideas.

Post concert discussion. Full Circle, Brussels 9 6 22 Photo Malene Skaerved

Denmark 10-14th June 2020

Taking the boat from Fyn to Skarø 11 6 22

These past four days have been an opportunity to travel slowly, to talk, to think, and watch. Malene and I continued our journey north from Brussels by train – via Cologne, Hamburg to Odense. One of the themes, of Knowledge Exhange, is movement: of people, of animals, of music, of instruments, of ideas… the train journey to the Danish border heated up the ideas, in a similar way to standing on the fringes of Morecambe Bay a few days ago: not least because that area of Northwest England was, and is, extra-Danish – as Vikings who were driven out of Ireland came there and had to negotiate with the ruling Danes, who had established their power base in York/Yorvik. With regard to the train journey, from Hamburg to the Lillebælt, I the porous nature of the definition of the land, as German or Scandinavian, or even Flemish, is best witnessed in the train depots on either side of the border. A sad little old Deutsche Bahn shunter, still hard at work at Haderslev, and not for DSB, many kilometres north of the border at Padborg, made that point eloquently.

DB Köf II Shunter 11 6 22

Looking at this, as our DSB train ambled past, I thought about the 17th Century piece I played the night before, in Brussels – on a Lombardy-build 16th Century Violin, which had found its way to Paris by the 1600s: Thomas Baltzar, arrived in the UK during the Commonwealth, established himself as the greatest violinst in London, dominated the returning Charles II’s Private Musick. and was dead by 1663. In London, he was, known (as we know from the diarist John Evelyn, as ‘The Lubicker’). Today, we blithely think of this as a German City, but of course, for most of its history it was no such thing, and during the upheavals of the 17th century, Baltzar’s time, after its status as a Hanseatic city had declined, it was variously dominated by Denmark and Sweden, and would be part of the territory claimed by Denmark up till the two Slesvig-Kriger of 1848 and 1864. Indeed, other Lübeck-born migrants to the UK in teh 17th century – there are graves in the Wren church of St James Garlickhythe, were regarded as Danish…although they most likely spoke Danish and German.

Our first stop in Denmark was in Fyn. This is so important to Malene, as this is where she grew up, but also the home of the writer most important to her; the greatest traveller of all storytellers, Hans Christian Andersen. Both she and I have a real sense, that when you walk Ramsherred, and Bangs Boder the poor streets where he grew up, that he is all around. Whether or not the building today celebrated as ‘H C As Hus’, actually is, we both have the sense, that if we peer into the windows, lean on the wall, that he will look back at us, that connection might be made, and it is that connection that we all seek.

Malene Sheppard Skaerved, den Fynske pige, udenfors HCA s hus, i Odense 11pm 11 6 22

The next day, though, it would be nature that would be overwhelming. The next morning, another train, the type that Danes (not so affectionately) call ‘en bumletog’ (‘Bummelzug’ in Deutsch), south to the port of Svendborg, and then a tiny ferry to the even tinier island of Skarø (2 km square, and home to ten families) for a family celebration.

Erractic Boulder on the north facing beach of Skarø 11 6 22

Once again, walking the shoreline of this exquisite island, we found ourselves in a glacial landscape. Though, Denmark is almost nothing but. Every pebble, every rock that you see, with the exception of the chalk cliffs on the south east coast of Lolland/Falster, has been rolled from somewhere else, every pebble is, like the rock about, an erratic boulder. At Leighton Moss a conversation evolved about whether there was any real difference in ‘earth-time’ between tidal events, once-in-a-century-odd landscape-altering events, like tsunami’s or catastrophic inundations, small tides, like in-and-out breathing, and perhaps, the grinding down of landscapes, a and the scattering of giant granite pebbles from the north by the two kilometre-high ice sheets of the Ice Ages. Talking to a painter after the concert, she spoke of her realisation that the landscape that she loved the most, the Alps, was in motion, like a rought see, and spoke of beginning to ‘see’ that motion.

Hare. warned of my approach by an Oystercatcher. Skarø 11 6 22

And, finding my way across a meadow at the western tip of the island, I was screamed at by an oystercatcher, whose, insistence alerted a huge hare to my presence. It first dropped its ears and laid low in the knee high grass, and then bolted, with the Oystercatcher still screaming blue murder, until I cleared the site. Meanwhile, I was assailed by Skylarks from knee height to the stratospheric. It’s all a reminder that birds taught us to sing, and provided endless inspiration for composers of very age and every culture. Here’s Edward Cowie’s skylark – the closest a violin piece has come to the sound and fury of this fearless animal.

At the heart of everything that I do, is an overwhelming, and sometimes difficult, faith in humanity. There’s nothing that I love more that watching people, along, talking, moving, still, happy, sad. There is an intimate grandeur to be found there, and it inspires me every day. Returning to Copenhagen, after three years away, gave me great opportunity to indulge in my people-watching, and to be reminded how central they are to the work of the artist.

Waiting for coffee .Vesterport June 13 2022

Malmo 16th June 2022

Over the next few days, the ideas which have been gathering since the visit to Leighton Moss have continued to gather, in concert, if you like with the evolving counterpoints between the natural and manmade worlds around which my Knowledge Exchange project is building. Perhaps this is best illustrated by the astonishing painted Krämarkapellet (1460-1510) in Sankt Petri kyrka, which, when it was built in the 1300s was the biggest town church in Skåne (then Denmark). All of the figures, many of them holding musical instruments, are woven about with leaves and vines. In an analogous way, the natural materials of string instruments are set in formal, architectural decorations…

Troubadour in the astonishing painted Krämarkapellet /Sankt Petri Kyrka 15 6 22

And, after an idyllic day by Øresund, the ideas start to coalesce around another important point of focus, the body, as my conversations with Bradley Strauchen-Scherer at the Metropolitan Museum, New York City. She, and that museum have been a vital inspiration in this inception and develpment of my project. Here’s just a glimpse of some of the work that I have already done with that institution as simple concert/talk given on two of their historic instruments, both by Antonio Stradivari, and each one in different setups.

On my return to the Metropolitan Museum after the interregnum of Covid-19, our conversations began to focus on the links between musical instruments and the human body. This is a complex and foundational idea for instrumental music, that all instruments offer analogy for the human form (internal and external). Obviously, this also relates to the body (any animal body) as a noise, song or speech producing instrument and the instruments as alternatives, even, maybe, as avatars, for that interweave.

German viola d’amore, ca 1700. Metropolitan Museum

I have lost count of the number of times, that I have reminded myself that the ‘naming of parts’ of the violin, is key to this relationship. Violins, violas, viols, cellos, basses, have heads, necks, shoulders, ribs, backs, bellies. Sitting in my hotel room here in Malmö, Sweden, I had an hours-long zoom conversation with Bradley, in New York, as we began our preparations for my return to the Metropolitan Museum, in August, for Knowledge Exchange. The conversation, as it always is with Ms Strauchen-Scherer, was enlightening, and surprisig. She reminded me that René Descartes described the organ, as image for for the workings of the human body.

‘You can think of our machine’s heart and arteries, which push the animal spirits into the cavities of its brain, as being like the bellows of an organ, which push air into the wind-chests; and you can think of external objects, which stimulate certain nerves and cause spirits contained in the cavities to pass into some of the pores, as being like the fingers of the organist, which press certain keys and cause the air to pass from the wind-chests into certain pipes. Now the harmony of an organ does not depend on the externally visible arrangement of the pipes or on the shape of the wind-chests or other parts. The functions we are concerned with here does not depend at all on the external shape of the visible parts which anatomists distinguish in the substance of the brain, or on the shape of the brain’s cavities, but solely on three factors: the spirits which come from the heart, the pores of the brain through which they pass, and the way in which the spirits are distributed in these pores.’ (Treatise on Man,” 166)

This lead to a conversation about the interior of musical instruments, of vibrating air, of breath, and I remembered the link between breath and fire. We talked about ‘prana’ the Sanskrit word for breath, “life force”, or life itself. The Vibrations within string and wind instruments rely on this vibration breath, as much as the operation of the human body. I remembered something that seemed important, that the Danish for ‘oxygen’ is ‘ilt’. The Danish ‘Ild’ translates as ‘fire’. This seems terribly important, in this moment.

The extraordinary viola d’amore shown here is one of the instruments which this project will explore at the ‘Met’. There’s such a lot to say about this. I will leave just one idea here. The instrument is almost ‘flat’, as it has no ribs, and the back is afixed directly to the belly. This means that it is very quiet. The only question that I would like to answer now is: ‘why?’. What is the quality of soft music, playing, voices, that is so important, perhaps more now than ever, this noisy age?

A place to practise. In my hotel room in Malmo 16 6 22

Over the next few days, the various institutions involved in Knowledge Exchange Violin will start to figure more and more in this journal. However, to finish today’s entry, I would like to introduce an important element in the exploration of the various instruments who make up this project – the compositional response.

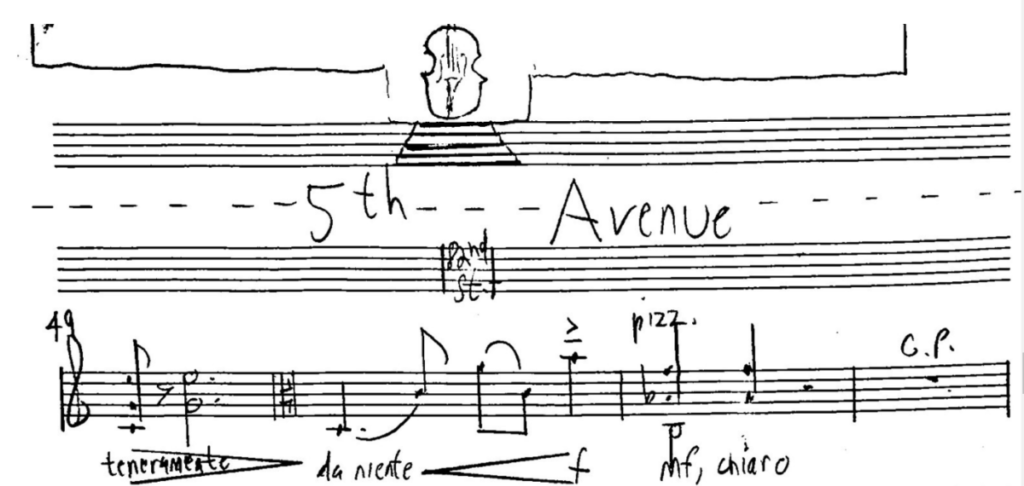

American composer Michael Alec Rose and I have collaborated intensely since we were introduced by the great George Rochberg shortly before he died. Our collabrations have involved deep dives into landscapes, painting, sculpture, spaces and much more. Michael has started a group of miniatures responding to the instruments and ideas in this project. Here’s a tantalising (I think) glimpse of one of these, ‘Rode Trip’. Watch this space!

Detail of Michael Ale Rose ‘Rode Trip’ For Knowledge Exchane Violin. 2022

Over the past few weeks, Michael and I have talked intently as to the nature of his response to the instruments and places in’ Knowledge Exchange Violin’. In addition, our collaboration provides a geological omphalos to the project, as, at the beginning of October, we will travel together to Utah to develop out shared work on his suite for violin – ‘Sedimental Education: A Stratigraphic Suite for Solo Violin’. Michael writes:

“In October of 2022, Peter Sheppard Skærved and I will make our way together to Utah’s Capitol Reef National Park, one of my sacred places in the world. There, we will carry onto higher ground our two decades of on-site collaborations celebrating various landscapes and artistic venues. This latest round of our performer-composer research takes us into deep geological time. At Capitol Reef, on the trail up to Chimney Rock, a visitor grasps 100 million years of Earth’s history all at once in the exposed layers of Triassic and Jurassic rock. For me, witnessing the compact vastness of these multi-colored strata feels close to the experience of Peter Sheppard Skærved’s violin playing: generations of instrument making, performance practice, and compositional expression are not only exposed, but in due time are made radiantly clear and mutually illuminating. It is a sedimental education. That’s the substance and the spirit of my six-movement suite for Sheppard Skærved.” (MAR June 14 2022)

This will not be the first time that Michael and will use walking as a tool for composition and collaboration. Michaels cycle ‘Il Ritorno’ was the

With Michael Alec Rose on Hayne Down, Dartmoor 30 11 13

result of just such an exploration, our personal psychogeography, of the great granite plate of Dartmoor, in South West England. This project brought together the walk, talking, writing, composing and drawing, and the result is a luminous celebration of human in the landscape, of water and rock, tree and lichen, life and death.

July 5th London Heathrow en Route to Washington DC.

After a couple of hectic weeks of recording, I am back on the road with Knowlege Exchange Violin. I am writing this sitting in Terminal Two o London Heathrow, waiting for my flight to Washington DC. There I will spend the week working with the team at the fantastic National Gallery of Art. More of this in a minute: first of all, I wanted to share the sheer happiness of Minneapolis Institute of Art wing of this project. A few weeks ago, I reported on the first rehearsals for our recording of French songs from 1790-91 Paris. Yesterday, I met with the soprano Héloïse Bernard and harpsichordists Julian Perkins, and recorded a group of 9 songs. None of these have been heard for over 200 years, and we are enchanted. It is as if the spirit of the great artistic salons of late 18th century France was immediately revenant. This is a spirit of delight, of intellegent play, a spirit that animated the great creative minds of the age: at any moment, I felt, Germaine de Staël, Giovanni Battista Viotti, Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, might walk in, start singing, playing, drawing, talking. This spirit of the salon, is what drives Knowledge Exchange Violin.

In preparation for my work at the NGA this week, I have been thinking about home. So far my work with the great Washington Gallery was resulted in a podcast –

-and a deep dive into the on show and catalogued collections of the gallery. This work occupied me in the summer of 2019, when none of us realised that we were headed for a two-year interregnum. Here’s the link to the post – https://www.peter-sheppard-skaerved.com/2019/08/a-new-focus-collaboration-with-the-national-gallery-of-art-washington-dc/

Henry Moore Knife Edge Mirror Two Piece 1976-1978 (National Gallery of Art Washington DC 19 8 19) 19 8 19

But I thought that I would take advantage of the NGA’s peerless collection of a great artist for whom music was so important and who treasured the part of London were I live – James Abbott McNeill Whistler, returned repeatedly to the community by the river in Wapping, LImehouse and Rotherhithe. Indeed one of the treasures of the NGA is his view of Wapping from the Angel Pub on the other side of the river.But it is his drawings and etchings of the place that I love the most. So I can begin here, right at home, with the Thames drawings done at the beginning and end of his career. No artist loved the place I live more. Here are drawings of a Wapping Wharf, Billingsgate (and wonderful rendition of longshoremen and porters), and, right at the end, a night study of moored vessels. I can’t resist the idea that he met one of my forbears. Like Turner, who also loved the place: Whistler drew and painted the people with as much relish as the water, the light, the mist, the atmosphere. Indeed, for both of them, the two were inseperable. Wapping was, perhaps, as much of a home as Whistler would ever know: so it’s where I will begin for now, with the place I know the best.

Whistler – Wapping (1859)

Of course, Whistler is useful for my work as a muscian/artist. He courted controversy, by giving his paintings musical titles (‘Symphony in White’ is his portrait of his lover Joanne Kifferman). There are a million ways to explore the links between the arts, from the idea of a painting which represents the making of music, to works of art which explore more conceptual links. Over the next few days, I will talk and explore with a fascinating group of collaborators from the National Gallery. I am keen not narrow the possible links which can emerged from recognising the shared language which Whistler spoke so easily .

Washington DC 6th July National Gallery of Art.

Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614) Allegory of Music

I am sitting with my morning coffee (its 630 am), thinking about the day. It’s going to be an exciting beginnig, as we will begin with a painting about music, from the turn of the 1600s, which is just coming into the gallery. While I was putting together my podcast about Bosch for the NGA, earlier in the year, they told me that they were buying a wonderful painting by the great Bolognese painter, Lavinia Fontana, and hoped that I would be interested in looking at it. I am thinking about Fontana’s extraordinary work as a pioneering woman artist, blazing a trail (at least with the benefit of hindsight) Artemisia Gentilleschi (1593-1653). Fontana’s masterpiece, painted in her 23rd year, depicts the act of music making; more to the point, it shows the artist herself making music, sitting at a spinet, or virginals. There is so much to say about this picture but lets begin with the obvious thing. This painting shows music being made, by a recognisable individual. The picture to the left, ‘Allegory of Music’ is, in some way, about music. There’s a difference. Exploring that difference is one of the themes which is beginning to emerge here.

Fontana. Self-portrait at the Virginal with a Servant (1577)

Let’s begin with a simple idea: what are/were beautiful instruments made for. It’s impossible to take a violin out of its case (any violin), withou the powerful sensation that you are holding something very special. It is intrinsically beautiful, and even before it makes a sound, that beauty has a number of elements. Reduced to binary elements, a violin is made from beautiful material, and it is a beautiful object. All art shares, or shared this duality: as Baxandall pointed out, a renaissance painting or sculpture celebrated the wealth of its donors through the quality of the pigments (and gold) or materials used in its making. And of course a painting or sculpture is formally beautiful (whether the subject depicted is beautiful or not – another question). A violin, or lute, is, speaking as simplistically as possible, exactly that. And like a painting, or sculpture, it is designed as much for silence, as for sound, to be seen and heard. Looking at the ‘Allegory of Music’ drawing above, lutes and the spinet/virginals are being played and there is singing. But there are two groups of instruments exhibited at the front of the picture-wind instruments on the left, and an oh-so-casual heap of bowed and plucked string instruments (inlcuding a hurdy-gurdy, a viola da gamba) in the middle. This is a collection, exhibited in the same spirit as the precious materials used in an expensive painting or sculpture. Musical instruments were assembled in the studiolo or Kunstschrank of what came (particularly in England) to be know as the ‘virtuosos’, alongside whatever precious curiousities and treasures were collected there. They were designed for that purpose, and exhibited and admired in just that spirit. Music played and performed (it’s perhaps important to make the distinction), was part of of that spirit. In many ways, nothing about this has changed, and to a greater or lesser degree, every room where music is made, reflects this spirit.

How we choose to present ourselves, in and around music, made or evoked, is, often very personal. The inscription at the top left of Fontana’s self-portrait, reads:

Lavinia Virgo Prosperi Fontane / Filia Ex Speculo Imaginem / Oris Sui Expressit Anno / MDLXXVII (Lavinia, a virgin, the daughter of Prospero Fonatana, made this image of herself in year 1577, using a mirror)

She wanted us to know that she was, is, the artist of the household. There is an easel by the window, but it is empty, hers. She is determined that no one will suggest that anyone else but her has made the picture. The mirror that she has used is hanging, like Vermeer’s would be later, on the wall, angled down, so that she can look up and down on herself. There’s an clear analogue between the angle of the mirror and the angle of the reflecting lid of the keyboard instrument, each reflecting, sound and light, bag to her, not unlike her admiring servant, who may, or may not be singing.

Here’s the wonderful image I am going to meet this morning.

Fontana- Portrait of Luciana Garzoni

Later the same day: Today was a day of people, and ideas. My main partner and collaborator at the National Gallery is the Kate Haw, who is in charge of Collections, Exhibitions and programmes. During the day, she and I met and swapped ideas with a fascinating series of groups of people. At the centre of the conversations, which were wide-ranging, was the idea of communication. What, why, and how should a museum communicate? What is its obligation to its communities, to its history, to its collections, and to the interweave of the arts.

It’s important to note that music has always been at the centre of the NGA’s approach – its concert series, which began during the Second World W, in counterpoint, with Myra Hess and Kenneth Clarke’s famous cycle of concerts at the eponymous London gallery, has never stopped, making it the longest running series of museum concerts in the world. This means, speaking personally, that I have enormous respect for this legacay, which, of course is in concert with the extraordinary long-running musical work of the Library of Congress, just up Capitol Hill, just a few minutes walk away.

Arriving at the wonderful East Wing entrance of the NGA, I sat down on the steps by the two-piece Henry Moore bronze, ‘Knife Edge’. This is the sibling of the similarly named piece which stands on the grass on Abingdon Street Gardens, just over the road from the Houses of Parliament. It struck me, sitting there, that one could hardly wish to have a better illustration (on this of all days, with a the meltdown in Westminster) of the importance of acknowledging how art is affected by the context in which it is experienced. These similar sculptures are renmy dered utterly different, by place.

But then I looked up at the entrance to the gallery, and was delighter to see the banner over the entrance: ‘The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler’, an exhibition celebrating the very artist and friendship I was talking about just a day ago – see my note above. When I was able to see the small exhibit at the end of the day, the picture which struck me the most, like my day, was, is, all about people. And it was drawn a few minutes walk from my home in Wapping. No artist of the late 19th century drew working people more beautifully, and more senstively that Whistler, and this drawing, made on the Ratcliffe Highway, now just the Highway, at the end of Wappin Lane, where I live, is a wonderful example. It also sings beautifully to the coluquy of voices which I enjoyed the whole of this day of discussion.

Ratcliffe Highway – James Abbott McNeill Whistler 1861

I don’t mind admitting that I take pride in these faces: these are, after all, my people, and I can hear the voices of my friends on our road, of their forbears, some of who knew, and were related to, my family, who lived and worked in this area for centuries. And this reflects the wonderful thing about my work, about the conversations during the day, about travel: people. I am very aware that on this trip to DC, I will not be doing any ‘touristy things’. There will be no trip to the Capitol, to the Jefferson Memorial, to the Smithsonian. The joy and wonder of any place is its people, and being welcomed into a community of ideas, of conversation, is for me, one of the deepest dives I can take into a place.

The most important thing about starting a conversation, for me, are, first of all. to avoid deciding what the conclusion will be before the talk begins. Secondly, and perhaps as important, is to ensure that no one feels that they will be locked into a commitment by taking part in a discussion. When these parameters are established, it is always fascinating to see how the ideas develop. In the morning, broad themes emerged, and I think that these will begin underpin my small profect. The most powerful of these was, is:

Learning

Curiously, excitingly, this broad theme found its way from a point, made by Sherri Williams, the Museum Education Specialist, that, when visitors were asked to articulate their expectations coming to the

My alter ego: Late 16th century Italian Lira player (ANON) – or Orpheus charming the beasts NGA 6 7 22

NGA – FUN – was at the top of the liste, and, when they left, something deeper had taken place. So the balance, the flow between these two things seems important. And this flowed, naturally, into an idea so important for musicians:

Play

The question of what play was, why it is important, and how/why/if it can be countenanced in the (very) marbled halls of a gallery such as this, droved much of the morning conversation. Interestingly, towards the end of the day, one interlocuter, very usefully challenged the notion that a gallery such as this should be involved in creating output, or anything, which is something to explore, to chew on.

Day Two NGA DC

A pop-up performance of Locatelli, de Machy, Evis Sammoutis and Viotti to finish my first two days with Knowledge Exchange Violin, working with the wonderful team at the the National Gallery of Art Washington DC. 7 7 22

The second day of exploration was, if it is possible, even more exciting than the first. We explored ideas of communication, the dialogue between the arts, intrusiveness in public spaces, the challenge of the salon, online communities, and much more. For me, the absolute highlight was a deep hangout in the sculpture galleries with Kate Haw (Executive Officer, Collections, Exhibitions and Programmes) and Michael Lapthorn ( Chief of Design). This was part of the gallery which I had not explored before, and it was wonderful to slowly talk our way back in time, from Rodin and Degas, back to the medieval era. Fascinating questions about the perceived relative importances of different art forms, from painting, to sculpture, to maiolica, emerged. And, as ever, the wonder, the excitement of materials was at the centre. Here’s an example: In the middle of a conversation about light, Michael revealed something wonderful about bronze:

‘It doesn’t matter how much light you shine at bronze, it just eats it up, swallows it.’

Naturally the conversation briefly swung, via event horizons, and Anish Kapoor’s famous/notorious ‘Vantablack’, to how we could think about this with sound, and with ideas. And then we turned a corner to find this.

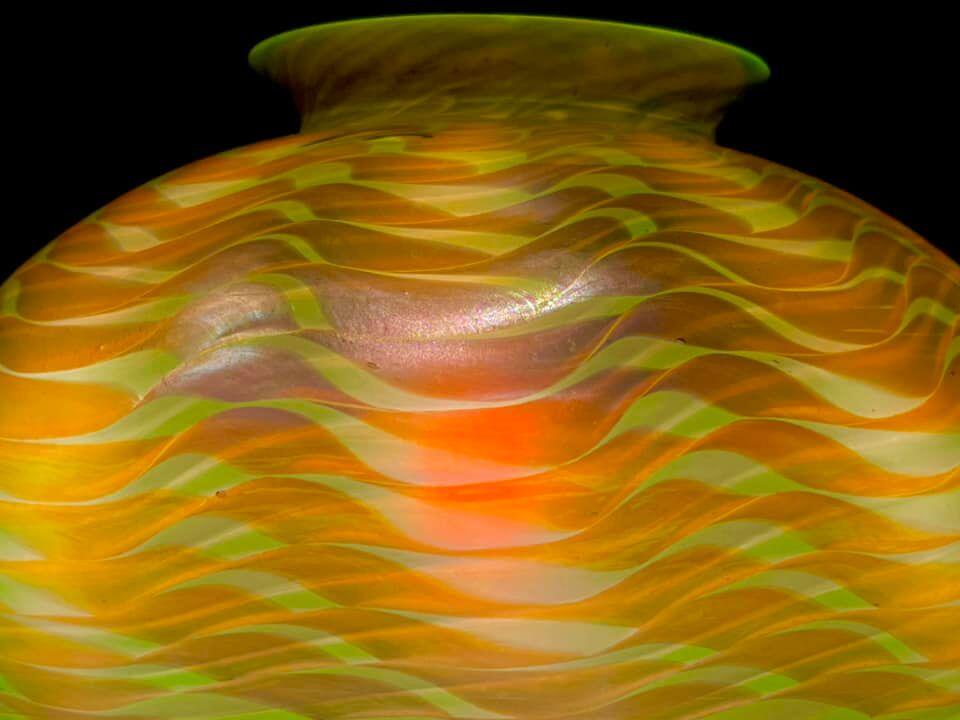

Chalice of the Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, 2nd/1st century B.C. (cup); 1137-1140

This is the the chalice, owned by Suger (1081-1151), the great builder abbot of the St Denis, and used to celebrate mass for Louis VII of France and Eleanor of Aquitaine, at the consecration of the new ambulatory of his abby in 1144. The sardonyx cup is set int heavily gilded silver mounting, adorned with filigrees set with stones, pearls, glass insets, and opaque white glass pearls. The cup itself was made in Alexandria over a thousand years earlier, in the 1st Century BC.

For the past two days, I had been talking about the celebration, the setting, of natural materials in exquisitely designed frames, like the the back of a violin. And here was the most extraordinary example, itself witness to history. Eleanor of Aquitaine, left Louis for Henry II of England in 1152, and was the mother of Richard I of England, John, King of England, Henry the Young King, Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, Eleanor of England, Queen of Castile, Joan of England, Queen of Sicily, Matilda of England, Duchess of Saxony, Marie of France, Countess of Champagne, William IX, Count of Poitiers and Alice of France. This is where objects, materials, art, symbols, mystery and history meet. And at the heart of it, the counterpoint, between the free-flowing agate bands and the pleats carved by an Alexandrian artist before the birth of Christ.

And, like so much, it has a French Revolutionary history too. On the 30th September 1791, with the nationalization of the monastic orders in France, the chalice was taken away from Saint-Denis and deposited at the Cabinet National des Médailles et Antiques. In February 1804, it was stolen from the Cabinet National, forced into a plaster bust of Laocoön, and smuggled to England, which was then at war with France. I feel sure, that I will be returning to this.

At the end of the day, to my delight, my dear friend and collaborator, the composer Evis Sammoutis arrived at the gallery, met with ‘my’ team and came with us to a wonderful corner of the sculpture galleries. There I did my favourite thing – to just get the violin out and play for whomever happens to be there. I played Locatelli’s ‘Il laberinto…’, de Machy, Viotti and Evis’s 1st Etude ‘Resonance’. We had no music stand, so he held his score up for me. There was great delight amongst the surprised listeners, a group of whom hung out and chatted with me afterwards, fascinated by the music, the notation, the materials, and the fun of chancing on music in a gallery. To see this performance, go to the top of the page!

In the evening, I found my self in the extraordinary museum over the room from my hotel, which itself, is a remarkable building: it was commissioned by President Andrew Jackson from the architect Robert Mills (1781 – 1855) as the General Post Office. And on the other side of the road another Mills governmental building – originally, the Patent Office, and now the National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Only when I completed the two days work in the National Gallery, did I dare go in there, and it was lucky that the museum was closing at 7pm, otherwise, I probably would not have left. that night. I would just like to offer one picture from this extraordinary collection, as it stopped me in my tracks, and reminded me of 1. the importance of the relationship to the natural world in my KE Violin project and, 2. how much my eye and ear have been influenced by the powerful American landscape painting of the 20th century.

Victor Higgins (1884-1949)- Mountain Forms #2 (1925-27)

This picture epitomises that, and reminds me of a wonderful short story my my wife, Malene Skaerved, where there is a natural sense of the landscape, of hills and mountain, as a body. This is, from eyes a defining characteristic of this American C20th school, and nothing epitomises it better than the painting yesterday. It was a painting that I knew well from reproduction: but there is nothing quite like the actuality, and running into it, alone in an empty gallery in the evening.

Back in London 12 7 20

I spent the last two days stateside in the USA in Philadelphia with the composer Michael Hersch, his wife the Latinist and historian, Karen Hersch, and some fascinating writers and artists. Michael is one of my closest collborators, and we have worked together exceptionally closely since we were introduced by the late George Rochberg, nearly two decades ago. Here is a talk about Hersch’s music which I did for Johns Hopkins University during Lockdown. I think that it gives an interesting overview into the weave of our shared fascinations.

One of the most interesting challenges of the Knowledge Exchange Violin project is to enliven and clarify my understanding of the relationships between the arts, and to be open to new influences, balancing the challenges and opportunities of working with large institutions with conversations, collaborations, sharing ideas with individuals, working independently. It’s very easy for institutions, of whatever nature, to miss out on the excitement, the creativity, the ideas that come from independent artists and thinkers. One thing that I can do, is to keep drawing attention to, and learning from these voices. And one of the most interesting things is how often one artist will

Roumanian masks ( including four ‘Capra/Goats’) from the collection of Adam and Nancy Sorkin. Philadelphia 9 7 22

introduce me to another. As soon as I arrived at Michael’s home in Havertown, Philadelphia, he grabbed a bottle of wine and led me next door. There he introduced me to a fascinating couple, Nancy and Adam Sorkin, whose house is filled with a wonderful collection of Roumanian folk art, most strikingly a wall of masks (related to, but distinct from the Austrian ‘Grampus’ traditions). In between Christmas and New Year, the ‘Mascatii’ (the masked men) chase away the evil spirits, helping the Sun to find its way back after the dark of the winter solstice, and to bring a good harvest, to bring the New Year in filled with light.

One of the dances and costumes central to this is the ‘Capra’ (Goat Dance): Masks for this can be seen on the left. I have written a lot about my interest in the circles of meanings around this word, with its links to ‘caprice’, cutting a ‘caper’ the Devil-as-Goat (see Goya’s ‘Black Paintings’) and even the word ‘Cabriolet’ and the link to the word ‘cab’. This is not the place to dig into this – you can find plenty of it on this website. But it is a salutary reminder of the vital link between all the arts and the rhythms of the natural year; for farming, hunting, and that all the symbolism in the fine art on the walls the National Gallery has this at its heart. In a conversation with the NGA Chief of Design, Michael Lapthorn, we discussed the challenge of communicating the myth systems underlying art, music and writing to audiences. It strikes me that the vernacular of such folk art can offer a fantastic link.

Adam Sorkin, who is Emeritus Professor at Penn State University, is one of the most distinguished translators of Romanian literature: he has published 65 volumes to date. He handed me his most recent book, a co-translation of the poetry of Traian T. Cosovei (1954-2014) On the plane home, I read this wonderful work, and was most struck by ‘Hieroglifa’ (the hierolglyph) :

So what it your body is sand?

So what if your embrace clasps sand in its arms

until it’s transformed into pyramids?

At the street corner, I’m there, the one who traffics in rocks:

the lapidary –

the hourglass man who sifts slowly between mourning and pity.

the man with scissors and tongs, with sickle and hammer …

anvils-

the rock-tamer, the sand transfigured

from pyramids to cathedrals…

Without mystery, without wonder: I, my love,

who made love and prayers from stones.’

(Night with a Pocketful of Stones, Broken Sleep Books, Talgarreg, Wales (2021)

Sculptor Chris Cairns. Dunkin’ Donuts, Havertown 10 7 22

And then it was onto another wonderful conversation, with the sculptor Chris Cairns. This was a great opportunity to think about salons. Chris and Michael Hersch meet regularly to talk over endless cups of coffee, in the Westchester Pike branch of Dunkin’ Donuts. There, over fantastically non-descript coffee, they sit and talk for hours about everything that is important to them: this is their equivalent of Johannes Brahms’ beloved ‘Red Hedgehog’ cafe in Vienna.

Meeting up with Chris reminded me of the essential interconnectedness of all of our lives. He was directly responsible for my meeting with George Rochberg, in 1998, a tectonic event in my artistic life, and one which led to my meeting Michael Hersch six years later. The reason was that his assistant, when he was teaching at Haverford College, was Niclas Berry. Nic’s partner and later wife, Heather Oakley, was/is my wife Malene Skaerved’s friend at nearby Bryn Mawr College (the greatest women’s college in the USA). We have been family ever since. Heather noticed that I was playing the music of George Rochberg (who I had not met), and said that she had met him at Chris’s studio. She made the introduction, and I took the NE Regional Train down to nearby Newtown Square, where George lived, and our collaboration was born. When I released my recording of George’s ‘Caprice Variations’ the cover featured a group of Chris’s many sculptures of George’s head.

Indeed, I became a part of this dialogue, between the two great artists and thinkers, when Chris presented his ‘Rochbergtorium’ in 2005, the year that George died. I was never able to visit this installation of sculptures and objects, but my recording of ‘Caprice Variations’ was playing on a loop in the exhibit, so it felt as if I had been there: perhaps I was. And then George died, and I never came to see Chris in Philadelphia. Meanwhile, he built an ever-more intense dialogue with Hersch, as was I, completely independently, so our meeting in Dunkin’ Donuts finally closed the circle, and opened the door for a newly revivified communication.

Talking with Chris reminded me of the mephitic, even sulphurous quality of Rochberg’s discussions; they both share a powerful sense that great art is something that should be protected, furiously, against those who would cheapen it, degrade it. Chris’s extraordinary work, like George’s feels as if it has been torn from within him: this is beauty and truth which is impossible without a price. In 1998 George wrote:

‘The fire in the mind translates into a living imagination that, as William Butler Yeats says, “divides us from mortality by the immortality of beauty… Passions, because most living, are most holy…”

Sunset over Dunkin’ Donuts. Westchester Pike 9 7 22

Our conversation only ended, when the staff of Dunkin’ Donuts chucked us out, into the most beautiful sunset, of Virgilean beauty. Michael was delighted: ‘Pennsylvania Sunsets: it doesn’t matter what else happens – they’re always beautiful here. Always.’

The following morning, this conversation continued in the extraordinary space of Cairns’ studio. Chris was not there, so it was just Michael and I, but it certainly did not feel as if we were alone. Far from it.

I probably talk far too much about the importance of the workshop as a creative space, and of my question, which, perhaps, I take too far, to prise the workshop door open, literally and figuratively. Cairns studio is housed in an innocuous stone-built industrial building, and as Michael put it, as we were standing in the midst of it: “We are surrounded by 50 years work!”

Moulds and sculpture stored in the Cairns Studio 10 7 22

Playing amidst Chris Cairns amazing figures 10 7 22

I think that where I will leave this today is by drawing a straight line of comparison, between the notion of playing in a gallery space and playing in such a workshop. Like Thorvaldsen and Watts before him, Cairns’ space has always been both a place to work and to show. In fact, it is fair to say that, one of the seed for the modern gallery experience, is the practice, in the 18th and 19th centuries in particular, of visiting an artist’s work in their work space. It is something with which I am familiar of course: I hav

e improvised in Anthony Gormley’s studio while he drew, worked with Jan Groth in his studio in Oslo, and performed in shared studio spaces in Dover (to select just three). It’s also worth noting that, of course, it is very different to play around an artist’s work in private and in public. But thinking about my conversations with the team at the NGA, and perhaps especially bearing in mind the conversation around the Fontana painting in the conservation room (also, of course, a workshop), there is much to be gained from asking ‘what can the experience of one bring to the other?’

August 4th plus – Back in the USA, and the project continues

The Landmark Center, St Paul. Minnesota. Home of the Schubert Club Museum. Built by Willoughby J. Edbrooke in 1902 as the United States Post Office, Courthouse, and Custom House for the state of Minnesota

4/8/22

So I have come to St Paul Minnesota, for the next stage of Knowledge Exchange. Here, I am working with two very different institutions, one a large, public art museum in Minneapolis, and the other, the epitome of a small, perfectly-formed, collection, the Museum of the Schubert Club Museum, St Paul. It’s been my pleasure to work with the museum on a number of projects for the past 5 years. These have focused on my interest in, and research into Ole Bull (indeed he loomed large on this visit).

However, I wanted to take the opportunity to dig into one the museum’s treasures, its extraordinary collection of letters to and from composers and musicians, stretching from Mozart and Haydn to the present day. I was hoping to dig into the letters without prejudice, to not decided what I wanted to find before I looked. This is an over-riding concern for me, for the whole of Knowledge Exchange, and I was, yet again, inspired by by the themes and voices which emerged.

So I settled in for 6 hours with as many of the letters I could get to in one day. They came at me from all dates and countries, dealing with questions and issues large and small, from the quotidian to the profound. In one, written by Bela Bartok in 935, the composer complained that that an officious ‘Cerberus’ prevented him from going into the violinist Adila Fachiri’s dressing room to see her and to listen to part of her concert backstage, which would have been good, as he was not feeling well.

Fachiri, born d’Aranyi, was one of three musical sisters Bartok taught before the First World War. Two of them, Adila, and Jelly, became world renowned musicians, inspiring composers including Ravel, Vaughan Williams, Holst, Wellesz, and indeed, Bartok himself to write works inspired by their luminous playing. Adila was particularly renowned for her work with Leoš Janá?ek, and both violinist sisters made their homes in London.

This letter, as well as letters from Chopin, Elgar and Shostakovich, dealt with the question of musicians’ health. I realise that this is a theme which is important to me, and which, alongside some of the questions and ideas around the natural world, which I am endeavouring to explore in Knowledge Exchange, is a theme which recurs. In another letter, written in 1966, Dmitri Shostakovich wrote that his doctor had announced that the medication he had proscribed him had completely cured him: with the benefit of hindsight it is impossible to not think about the situation, eight, nine years later, when a stroke incapacitated him so much, that he had to write his last work, his viola sonata, with his left hand, as his right was paralysed.

There are moments of pure inspiration to be found in the letters. Perhaps the most exuberant, the most uplifting (and undated) was written by the young Ernest Bloch, astonished at Eugène Ysaÿe’s insight into his music. He wrote: ‘I am not the only one who feels my music.’ It reminded me of the letter that Edward Grieg wrote about being encouraged by Franz Liszt’s excitement at his Piano Concerto. By definition, letters are about connection, the magic that happens when people make contact, share ideas, collaborate, and inspire each other. E M Forster’s dictum ( from Howard’s End) ‘Only Connect’, is going to be key in this project. I will return to the detail of the Schubert Club materials later.

by the young Ernest Bloch, astonished at Eugène Ysaÿe’s insight into his music. He wrote: ‘I am not the only one who feels my music.’ It reminded me of the letter that Edward Grieg wrote about being encouraged by Franz Liszt’s excitement at his Piano Concerto. By definition, letters are about connection, the magic that happens when people make contact, share ideas, collaborate, and inspire each other. E M Forster’s dictum ( from Howard’s End) ‘Only Connect’, is going to be key in this project. I will return to the detail of the Schubert Club materials later.

At the end of the afternoon, I was able to see some uncatalogued Ole Bull materials. Bull has always been key to my work and exploration in the Twin Cities, and what emerged here offered new insights into his work touring the USA. But I will return to that later.

One of the most important questions for me, with Knowledge Exchange, is the idea of ‘place’. In my conversations with at the Schubert Club, with Kate Cooper (Director of Education and Museum) and Barry Kempton ( Artistic & Executive Director), we have started to talk about who my work with the materials in the collection, and the instruments ( more on this anon), should reflect on the place of the collection in St Paul, and the story of how classical music found its way here with the European settlers.

By the St Croix River 5/8.2022

It is impossible for me to disentangle this sense of place from my deep love of this part of the Midwest. Each day that I have been here I, my? wife and I have driven out to the St Croix river to swim, and revel in the unbelievable beauty and natural riches of this land of prairies, woods and waters. My wonder at this is the underlay for everything I am doing here. Perhaps this is even more the case now, as the relationship between the arts and the natural world has become so key for this project. I have been coming to walk on the Eastern Minnesota prairie and to swim in this river for twenty years now. This year, there are more birds than I have ever seen: Ospreys, Golden Eagles, Honey Buzzards and Bald Eagles have been watching us swim, and large Kingfishers and many wading birds crowd the river back. I don’t recall ever seeing so much wildlife here. Something is going right: this is tempered by the apparent collapse of the Monarch Butterfly, which we used to see in huge numbers here.

Knowledge Exchange at the Minneapolis Institute of Art 8/8/22

It was wonderful today, to walk back in to the fabulous MIA Minneapolis. This has been one of my favourite places to work, and extraordinary

Filming with Nicole LaBouff at MIA 8 8 22

teams of collaborators, over recent years. Of course, thanks (!) to Covid-19, it was three years since I was here last. Today I met up with my long-time collaborator and friend, Nicole LaBouff (Associate Curator of Textiles) to film an interview about our work together on the upcoming exhibit ‘Revolution à la Mode’.

We were joined (remotely) by Rebecca Geoffroy-Schwinden (Associate Professor of Music History at the University of North Texas). Over the recent period of pandemic-separation, we three have been running a transatlantic salon about our work on this programme: appropriately enough, today’s session focused on the relationship between the vocal materials I have recorded for this exhibit and the evolution of salon culture and mores across the age of revolutions.

So we dived into the subject: today, the main theme which was explored, appropriately enough was the historic to-and-fro between the various arts and sciences. Rebecca made the powerful point that this is best understood in the context, the frame of the 1790s Fashion magazines in which the music I have recorded was first printed. She noted that, the notion of food, fashion, art, music, etc. being products sold, bought and enjoyed in a consumer society really helps to understand the way that the 18th century appreciated such stimuli: Tea, Coffee, Chocolate, Music, Art – appreciated through all the senses, and appreciated in similar and related ways!

We explored the question of salon culture in a number of ways. The question of open/closed salons came up. I pointed out the rather prosaic fact, that, from Hogarth in the mid 1700s up till newspaper reports in the 1800s, one of the most obvious ways that salons were ‘open’ was the open window onto the street. Newspaper reports of the 1830s report on crowds gathering outside the house of the oral surgeon Samuel Cartwright, when Paganini and other luminaries were playing. But, balancing this, was the notion of access, of the shibboleths and payment which were were necessary to get past the footman and flunkies: Cerberus at the door against unwanted interlopers. Whilst, as Rebecca pointed out, quite rightly, salons were not only open to the rich to those of ‘bon ton’, by the same token, they were closed, to the poor, to those without access, be it though class, money or password.

The age of Revolutionary France bought me back, of course, to instruments once more. It was in Paris that the Cremonese instruments of the

Viotti: the great lost portrait by his dear ‘amica’ Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Amatis and Stradivari really ‘found their voice’ most particularly in the hands of an Italian, Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755-1824). Much of the material that we recorded for this project, was first heard on the stage of the Théâtre de Monsieur, founded on 26 January 1789 by Marie-Antoinette’s coiffeur Léonard-Alexis Autier and the Viotti, in the Salle des Tuileries. These great instruments were at the very heart of the theatres where these arias were premiered. Indeed, when ‘le Monsieur’ moved to Salle des Variétés (St Germain) in 1790, the Viotti’s sixteen-year-old pupil Pierre Rode played a concerto by Viotti between the acts of Giuseppe Sarti’s Le gelosie villane on 18 October.

Just a glimpse of my collaboration with the wonderful team at MIA Minneapolis. Talking with Nicole LaBouff yesterday

Knowledge Exchange in New York City 10-12 July 2022

Manu Frederickx Conservator for Musical Instruments at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, working on the Grancino Violetta 10 8 22

So today, the first day back the wonderful environment of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, working with the brilliant and welcoming team here.

The main purpose of my visit here this summer is to map out the programme for recording and filming this autumn, and most importantly, to listen: to the ideas and inspiration flooding from my friends and colleagues here, and to the objects themselves, whether they are sounding or silent.