Percy Grainger – Room-music Tit-bits Nr.7 Arrival Platform Humlet

Composed 1908. 1910, 1912. For Middle-fiddle single (viola solo) or massed middle-fiddles

Last week I was bowled over by a film of the great wind orchestra conductor, Frederick Fennell (1904 – 2004), rehearsing and talking about Percy Grainger (1882 -1961) with the US Navy Band. It is a compliement to this great musician, that the clarity, candour and understanding with which he presented the music (‘Lincolnshire Posy’ 1904-5) was such that I could not resist the possibility of playing some Grainger myself, immediately! That, after all, is the fundamental task of the classical musician – to identity so deeply with them music that we play that it is the universal voice, to which the composer gives liberty, which rings clear.

I remembered that there was one Grainger piece for solo viola, or ‘middle-fiddle single’ as he called it – his ‘Nr. 7 Arrival Platform Humlet’. So I ordered the score from Schott & Co, who had originally published it in 1916 and the score, in the beautiful engraving of the interwar years, arrived a few days later. I got to work straightways, and was, and remain, delighted, as I hope the recording above will show.

On the first page of the socre, the composer wrote: ‘Arrival Platform Humlet’ was begun in Liverpool Street and Victoria railway stations, London (England), on February 2nd 1908, and was continued and finished in 1908, 1910 and 1912 (England, Norway. etc).’

It’s wonderful, one of the first true solo ‘character pieces’ for viola alone, and, of course full of the highly idiosyncratic English directions, which distinguish Grainger’s work: ‘With healthy and somewhat fierce go’, ‘The half notes at the rate of slow-trudging feet’ ,’ clingingly’, ‘feelingly’,’merrily’, ‘louden’, ‘lightly’, ‘mysteriously’, ‘toneful’, ‘rough’, ‘lyricly’, ‘louden lots’, ‘all you can‘ (nestled inside the final crescendo!).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this ‘plain English’ made me think about George Bernard Shaw (1856 – 1950) and especially, the direct language and reformed spelling which can be found in his Pygmalion – it did not escape my attention, that that play was written in 1912. Grainger’s Platform Humlet was begun in 1908, and finished … in 1912. But the link is far more than just fanciful – in his biography of Grainger, John Bird noted: “Whenever possible Rose [Grainger’s mother] and Percy would attend lectures by George Bernard Shaw. They liked his books and plays, and found a great appeal in his brand of socialism. Shaw unwittingly repaid their interest some years later when he chose Mock Morris and Shepherd’s Hey, as entr’acte music for the first London production of Pygmalion in 1914.‘

But it was not just Grainger who insisted on the use of English in scores. The year before Platform Humlet would be written, he met Frederick Delius (1862-1934), and they became friends immediately (and were both part of Edvard Grieg’s circle) . It was Grainger’s gift of his version of Brigg Fair which Delius developed into the eponymous orchestral work, and in 1914, Grainger was playing Delius Piano Concerto. The two were close until Delius died in 1934. Delius was also an advocate of the use of English directions in performance material.

Danish pianist Karen Holten (1879–1953 with Grainger

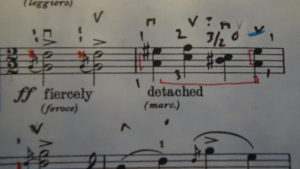

A closer look at the score of Humlet reveals, however, a certain, timidity. I am not sure, whether this was the composer, or the publisher, but the majority of the expression marks are doubled with miniature subscriptions in Italian, like these:

Of course, the funny thing is that, even today, musicians remain more comfortable with markings in Italian, than English. Whether we like it or not, these reforms did not ‘take’ any more than ‘GBS’s’ spelling reforms or the ‘Shavian Alphabet’ would enter the vernacular.

But editorial questions grabbed my attention, especially reading the following in Grainger’s introduction: ‘I am most grateful to Mr. Lionel Tertis for his kind and splendid help with the bowing and fingering of this edition for middle-fiddle …’.

Now I have to clarify my position – I am a fervent admirer of Lionel Tertis (1876 – 1975) as a muscian, as an artist and as an indefatigable pioneer. However, my admiration does not stretch to his technical editions. He’s not alone: there’s no violinist that I admire, revere even, than Ginette Neveu, whose recordings are for me a summa of what can be expressed on the instrument. But I am driven to distraction by her editorial work on the Honneger Solo Sonata and the Poulenc Sonata, which, in both cases, seems to misconstrue their composers’ intentions.

My expectations were met – the fingerings which Tertis has provided are dominated by unimaginative 3rd-5th position-work – every string player knows, in their heart, that this is lazy, In addition, there’s a misunderstanding of the fundamentally open, hopeful character of the piece, and the instrument is muffled, when it should sing out. Tertis’ suggestion are marginally more useful when the piece gets into more remote keys, away from the ‘ringing’ area of the ‘middle-fiddle’.

It was clear to me that Tertis had not spent much time with the piece, and I wondered if he had ever tried to play it with his markings. After all, his performance of Grainger’s Molly on the Shore is by any standards, fantastic, which perhaps explains the composer’s effusive gratitude in the score.

But then I remembered what had made me initiallyuneasy – something I had last read 25 years ago. I pulled down Tertis’ autobiography My Viola and I and turned to page 36, and all became clear … but I need to take a step back.

Grainger described the piece as ‘The sort of thing one hums to oneself as an accompaniment to one’s tramping feet as one happily, excitedly, paces up and down the arrival platform’. So let’s join Grainger on that ‘arrival platform’ – and I am pretty sure that he was standing under the (still-astonishing) roof of Liverpool Street Station. It’s a station that I know very well, as I grew up, and still live, in East London, and one of the ways to my parents’ house, is along the former Great Eastern tracks to the the terminus at Chingford, on the edge of Epping Forest. But Grainger is waiting for a different train, ‘bringing one’s sweetheart from foreign parts’.

There’s would have been a very good reason that Grainger was ‘tramping … paces up and down the arrival platform’. The winter of 1907-1908 was, like the year before, spectacularly harsh, with a great spell of snow in February, two feet of snow in the south east the following month, and on the 8th April, the heaviest fall of snow ever recorded in that month would arrive, along with temperatures of -12 centigrade.

We also know that this would have been a night-time scene. If Grainger was waiting for a train arriving at Liverpool Street Station, bringing a ‘sweetheart from foreign parts’, he was expecting the night train from Harwich – the only customers permitted on these trains were steamship passengers. ‘The ‘Boat Train’ left Harwich Parkeston Quay at 830 pm, and took 90 minutes to travel to London. The introduction of powerful 1500 Class 4-6-0 locomotives in 1912, would shave 3 minutes off the time.

The passenger that Grainger was waiting for would have travelled to Harwich on of a ship of Det Forenede Dampskibs-Selskab , better known today as ‘DFDS’. In 1882, DFDS negotiated with the Great Eastern Railway to sail from Esbjerg, in South Jutland, and dock at newly build Harwich Parkeston Quay. All the other ships using Parkeston were the Great Eastern’s own.

If Grainger was waiting for a ‘sweetheart from foreign parts’ on Liverpool Street Station in 1908, then there’s no question who it was – the Danish pianist Karen Holten (1879–1953). The picture above of the two of them , was taken on the Jutland coast, north of Aalborg, in the summer of 1909 – they were lovers and corresponded, in Danish, during the eight years that Grainger lived in London. They remained friends until Holten died in 1953. The outfit Holten is wearing, in the photo was her version of a Danish National Costume, and can been seen, much repaired, at the Grainger Museum at the University of Melbourne.

As soon as I pulled down Tertis’ autobiography, I realised the reason for my confusion regarding this piece. My my memory of Tertis’ somewhat unreliable (as he admits) recollections was causing problems. It’s worth remembering, that, like me, Tertis was an East Ender, who grew up in Whitechapel, just a few minutes walk from where I am writing this. In his early childhood, he lived at Princelet Street, which is roughly 500 yards from Liverpool Street Station. I note this to put it in counterpoint to his vagueness as to the locale of his remembrance.

Tertis wrote: ‘On one occasion – whether in London or America I cannot remember – he invited me to come to a railway station to meet his fiancée. While walking up and down the platform, he sung a tune, bouche fermée, a strange sort of noise to my ears to say the least of it, and when I asked him what it was replied that it had just come to him, that he would write it out and dedicate it to me for unaccompanied solo viola and would give it the title’ A Platform Humlet’.’

The next sentence explains the odd editing work which Tertis did on the piece: ‘ However, when I received the manuscript and played it through it sounded so devastatingly ugly that I never performed it either in private or public – neither do I remember to what infernal end I consigned it!’

I wonder if Grainger ever knew. Tertis made a number similar errors of judgement – in the next paragraph he outlines his refusal of the Walton Viola Concerto written for him at Sir Thomas Beecham’s suggestion, and how he also declined to play one of Hindemith’s concertante works with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.

But I want to leave you with Grainger waiting for his ‘kærste’ on that freezing station – well after 10pm on a winter evening, as the train is ‘belated’ – perhaps there was snow on the line, or the points had iced up. No matter, he hums joyfully to himself ‘as one happily, excitedly, paces up and down the arrival platform’. It’s a wonderful musical depiction of pure happiness, and Tertis could not have been more wrong!

Reading:

Lionel Tertis – My Viola and I (1975), Chrisitan Wolmar – Fire and Steam (2007), http://www.harwichanddovercourt.co.uk/ , https://www.weatheronline.co.uk, https://grainger.unimelb.edu.au/ ,

Posted on July 23rd, 2020 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved