Canon 22 12 19

Over the next week, I am going to talk a little bit about how musicians choose what to play. This might seem like a most prosaic topic, but it goes to the heart of who we are, and how we communicate.

So I am going to begin, here, with what I call my ‘working shelves’. This is not my music library/collection, but rather the constantly morphing piles of what has been on my music stand – and what will be. As a general rule it stretches about a year in either direction (into the past and the future), functioning in some ways like the high-watermark of an exposed beach, and at the same time, a musical ‘go bag’, or ‘what’s next?’, of concerts, recordings, and perhaps most excitingly of all, nascent and incipient projects.

By way of example, if you look in the middle of the shelving, you will be able to see a bound ‘volume 1’ of ‘Norsk Folkmusikk’ – which contains about 700 traditional ‘Slaater’ for Hardanger violin. I am gradually studying these (I perform about 15-20 so far) but am on the way to a project which brings these together with the ‘256’ the collection of Danish ‘Spillemaend-melodier’ made at the end of the 19th Century. I am not sure how this is going to manifest itself, but it’s ‘on the way’ and I see this volume every day, and that, I find, is exciting.

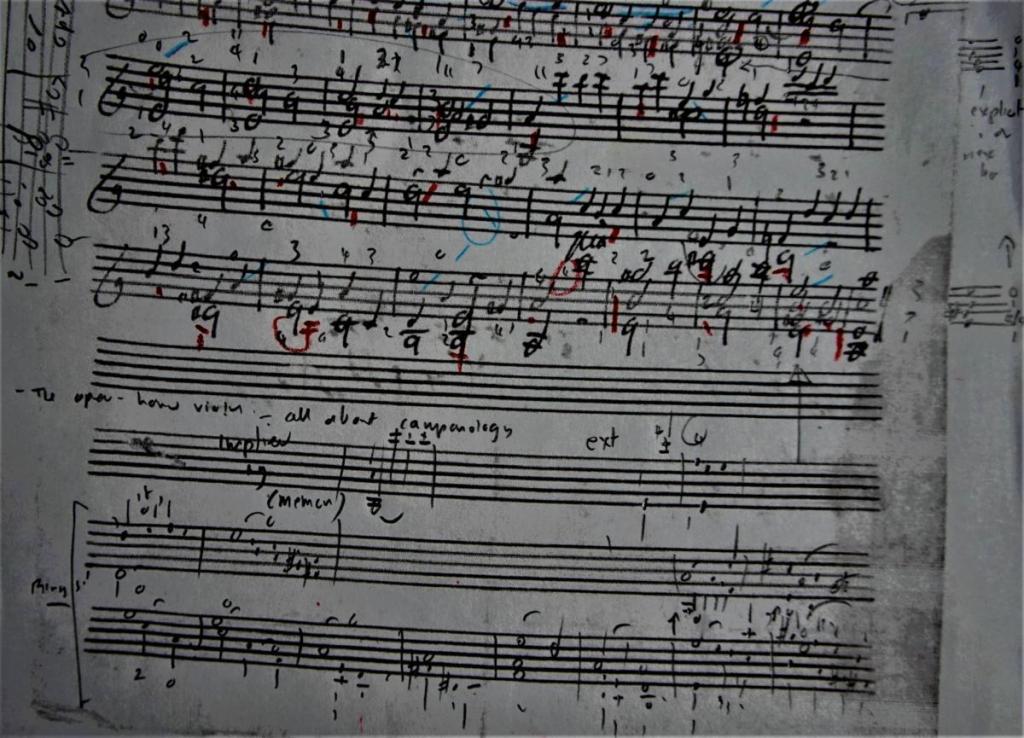

Very often, what finds it’s way onto the practice desk, I find, is the result of being ‘eyeballed’ by my shelves. The past week offers an example. I came out of a particularly uplifting recording of 17th century solo works at the beginning on the Monday, and hit the ground with some what of a bump the next day (exhaustion). It’s Christmas, so there are no concerts until the turn of the year. By Wednesday, I was in full withdrawal, and the only solution was to learn something new. The score of Hans Werner Henze’s astonishing viola concerto had been looking at me, somewhat balefully from the top of the shelves, for months, and I am exploring an extraordinary early 17th century instrument, so the two found each other.

It was funny, because the work proceeded without a plan: by the end of the week I had broken down the score technically, and the piece had found its way around the viola and into my imagination, and my dreaming. Something has been begun, and the project has started to take shape in my mind, a companion to my recordings of the 4 concertante works for violin and orchestra and the violin/viola sonatas.

But to begin at the beginning, how does a musician start to chart their own path as an artist? In every case, the answer will be different, but one of the routes that we take concerns choice of repertoire. At some point, and it is different for each artist, there will have been a private/public declaration of independence from the pieces prescribed for us by teachers. The reaction of various teachers to these declarations will be important in conditioning the direction/directions which we take.

I was not a terribly imaginative young violinist, so, in my case I divvy-ed up my practice time between the material which I was supposed to be working on, and the pieces, which I found exciting. Frankly, it was difficult to spend much time excited pieces like the Max Bruch G minor Concerto when you could sneak the cadenza of the Shostakovich 1st Concerto or Bartok’s 1st Concerto (an early obsession of mine) onto the stand. My ambition, my hubris, outstripped my technical means and musical understanding, and it certainly undermined my ‘real work’. However, my teacher and guide, the wonderful Ralph Holmes, took the bull by the horns, and decided to confront me, when I was 15, with the Beethoven Concerto, and I found myself, terrified, facing down the challenge of this piece, with the obligation of bringing it to lessons, and performing it with orchestras, probably, much too early. But the sense of excitement, the challenge of what felt like space travel, was infectious, and offered a rush which I sought in everything, whether working with music from the past or our own time. I suppose that a piece of music has to offer such a thrill as that early work with the Beethoven, and then I can’t wait to make it part of me.

Some of my teachers took a less charitable view of my determination learn and play far more than was advisable. Manoug Parikian and I came to a sort of detente when I was 18, and made a deal, based on his refusal (which I respected, up to a point) to teach pieces which he did not know. So I studied Bach, Beethoven, Prokofiev and so on, with him, at the same time as performing the pieces that he did not play (and sometimes not like – concerti by Weill, Hamilton Harty, Henze, sonatas by Benjamin Dale and contemporary works). What Manoug taught me was simple – that we should treasure the works which we choose to play, and he had a profound understanding of what I might like, or come to like. Shortly before his early death, he came into a lesson and handed me a score: ‘This is, I think,’ he said, ‘the greatest work ever written for two violins’. It was the Alan Rawsthorne Theme & Variations. This would become one of my favourite chamber works – I built a recording around it, and loved discussing it, years later, with Rawsthorne’s greatest disciple, the late John McCabe.

Enquiry 23 12 19

Last night was fascinating. For the first time, I was able to spend some time with a fascinating transcription – two movements from Pergolesi’s Stabata Mater, made by the astonishing Swedish violinist/composer Johan Helmich Roman ( 1694 – 1758). Working with a transcription can often tell you so much more about a composer/performer than their original works, as the contortions that they need to go through, in order to fit someone else’s music, or another instrumentation, onto their solo instrument can teach so much about their aesthetic and technical approaches.

But for now, I want to talk about the moment of discovery. For the musician, the discoveries that we make have, to put it gently, restricted impact. In our minds (well certainly in my mind) learning a wonderful new piece, or unearthing something lovely from the past (often found like these endleaves of well-known material) – in our minds, these revealings are revelations, like finding a pulsar, or a new species. They clearly are not, in the big scheme of things, yet, something, perhaps something vital has happened. What is that?

Clearly, it would be simplistic to reduce this to just one thing, as it is many things – but … what links every possibility is a sense that contact has been made. Contact with someone else, alive or dead, with a object of beauty, a virtue, a truth. This contact happens when discovery, in our case, is set ringing, singing.

Let’s simplify, grotesquely, for just a moment. When I study contrapuntal works like this, written or arranged by players in the 17th or 18th centuries, I want to know how they hear and think. For we string-players, hearing and thinking is expressed, almost entirely, through the hands.

Remember (not to self), music written and played up till the second half of the 19th century was written and played by improvisers. Chordal music on non-fretted string instruments, especially in extemporisations, relies on set patterns of movement (licks) and set chord positions for the left hand. So I begin work on pieces like this by writing a list: a gamut, if you like, of all the hand-positions that the composer uses in the piece. If you compare such lists built up from say, Westhoff, Colombi, Matteis, Bach, and so on, there is lot of overlap, of course. But each composer will, most likely, ask you to do something that you have not encountered before, a chord, hand position, movement, which at first seems obvious, but then it dawns on you, that you have never done. It’s like a word or a number, which you have read or seen, many times, but never said out loud. The shock of the familiar. And the convocation of such novel familiarities is one way that the personality of a composer becomes clear, in our hands.

You will notice that, in this extract from his Pergolesi transcription Roman drifts into the alto clef. This in itself is not noteworthy (after all, violin music at the time was always written in at least three clefs, to stay on the stave-Bach uses Alto, Treble and Soprano in his violin writing, sometimes all in one piece – have a look at the MS of the Chaconne). But the fun thing about this example, is that this is a composer at work, thinking out loud-he tries it for a bar and a half, and then doesn’t do it again in the three pages of Pergolesi, despite spent a lot of time at the bottom end of the violin. This makes me smile: it’s another glimpse of my collaborating composer, in the room with me, just back in the early 18th century.

Repeat 24 12 19

I am fascinated by cycles, in music and, well everything else. One aspect of them which intrigues me, is whether, or not, a creative artists recognises they are working on a cycle: it’s pretty clear to me, for instance, that Giuseppe Tartini set out to write what we might now name a ‘cycle’ of 26 Sonate Piccole which then occupied many years, whereas there’s no evidence that Beethoven every regarded his 32 Piano Sonatas cyclically, whereas his great student, Ferdinand Ries, did.

The cyclic imperative finds its way into smaller groups of pieces, of course, and I do not deny that I find it in works ranging from Cesar Cui’s 24 piece set, Kaleidoscope as well as George Rochberg’s Caprice Variations, which can be seen as a collection of 50 potentially free-standing pieces.

This all came to mind yesterday, which was the Danish ‘Lille Juleaften’, when the Christmas tree goes up and is decorated. The boxes of ornaments come down and are laid out on the table. Like many families, there’s a hodge podge, reflecting the three countries (UK,DK,US) which are our make-up, ornaments found in special places (a rocking horse from our honeymoon in Rome, a tacky souvenir from a trip to Niagara Falls or from a glass-blowing village in Germany), decorations collected by dear friends on their travels – an Emu egg is a particular favourite, or memories of people that we have lost. This is all then bound together briefly, with the chains of Danish flags, the candles, and celebrated with the miracle of a tree in our living room for a week or so. It’s a self-portrait of us, and the assembly makes a cycle.

More a little later, but now I have a goose to attend to.

GOD JUL!

Posted on December 22nd, 2019 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved