This short essay is an introduction to the concert I give at the Pharos Contemporary Music Festival, Nicosia, Cyprus on October 6th 2019

LINK to Concert

‘The violin is an astonishing ‘time machine, a 400 year old object bringing the old and new music to life, offering new visions of futures and pasts still unheard. My long-term collaborations have resulted in new hundreds of new works, whilst, at the same time, the violin takes me on journeys of discovery back through the centuries, showing me lost wonders, like the ‘Klagenfurt Manuscript’.

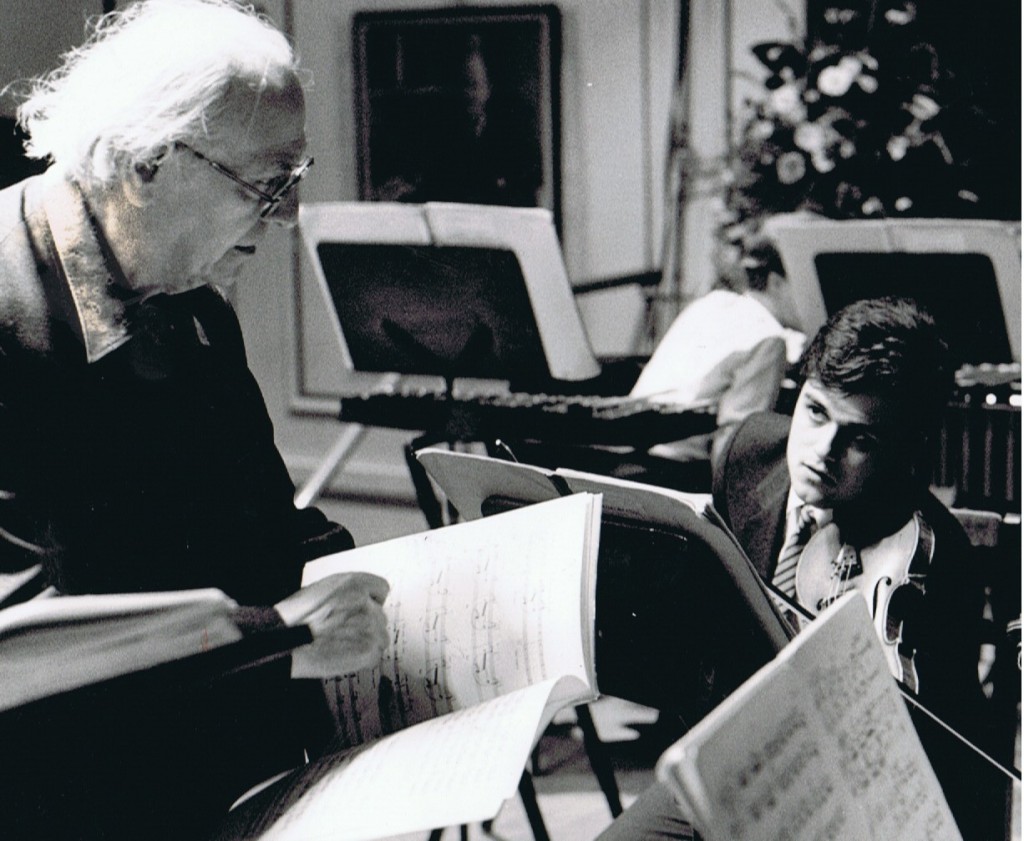

As a young child, I was fascinated by travellers of all types, most particularly those adventurers who sought out links between past, present and future. My (enlightened) church Sunday School gave me a my first book on the voyage of Charles Darwin, and my first serious violin teacher handed me the works of Patrick Leigh Fermor, books on shamanism, and chatted to me over breakfast about the conversations that went on at night, under the windows of her 11th century house, in 17th century French, whilst insisting that this nine-year-old play Bach as if he was in the room. I was not brought up to respect the limits of place and time.

As well as having visionary teachers, I was lucky to work closely with great composers before I was out of my teens. I grew up loving the Hugo von Beckerath painting of Johannes Brahms at the piano, lost in music and his cigar smoke. So I had a sense that a composer should be like that, somewhere between Moses and Merlin. And so it proved; first collaborations, with Tippett, Henze and Messiaen , proved life-enhancing and terrifying in equal measure. At the same moment, I began to work with composers of my own age, forming collaborations which have grown (if not necessarily matured!) over decades, and then I had the chance, ever increasing, to work with great voices who were and are, younger than me.

And this teaches me, that human creation and inspiration does not view Time as an obstacle, not even much of a challenge. But the composers also showed me something else: they taught me about how to collaborate with the music, the musicians of the past, who can’t ring me up in the middle of the night, to check that I am practising, like the late George Rochberg used to do.

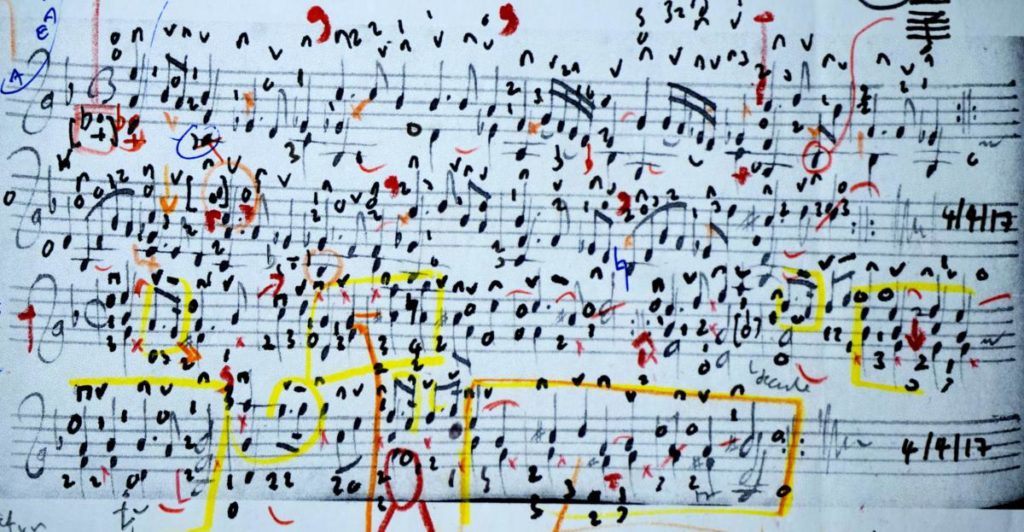

This year, I completed the first ever recording of the ‘Klagenfurt Codex’ an anonymous collection of over 150 works for solo violin from the 17th century. This is the work of a composer of the first order, using extraordinary re-tunings. The manuscript was discovered in a convent in present-day Slovenia; it was most likely to be the work of a nun-violinist. On first being introduced to the manuscript by the Landesmuseum in Carinthia nearly three years ago, I shut myself away with my violin for five days, decoding the very personal notation used by this anonymous composer, writing scores for their own use. Soon I was overwhelmed, emotionally, something that does not often happen in the practice studio. I realised that, in Peter Shaffer’s words that ‘I was staring through the cage of those meticulous ink-strokes at an absolute beauty.’ But, more than that, I had the most powerful impression that the composer was in the room with me, guiding me: a new collaboration had started, informed by the time I spend with living composers.

I find it fascinating how much my work with living composers involves the exploration of other things, either as inspiration, stimulation, or counterpoint for the work in progress. These ‘other things’ often come from, or deal with the distant past. And this is how it has always been in human creativity. When JMW Turner wanted to tell the story of Dido rebuilding Carthage, he painted the North African queen in a Roman city with Corinthian columns, based on paintings by Claude Lorrain, two centuries older than he . But Turner’s painting style was considered alarmingly modern by his contemporaries, offering a way forward that would be seized upon by the Impressionists and beyond. He like our composers, very often seized on various pasts to light his way to our future.

I relish this interplay between past and present, and most especially in my long-term work with composer Evis Sammoutis. We collaborate regularly on both sides of the Atlantic, exploring our shared fascination with the idea that music and instruments the subject and objects of constant change. In recent years, we have found illumination for this work in the layers and palimpsests of with the layers of Nicosia, provoking us both to produce new works in response to the sounds, textures, architecture, music and poetry of medieval Cyprus.

I like think of what Evis and I have been able to do over the past four years as, ‘deep hanging’ out, in the history and textures of this ancient and modern City. I will leave it to Evis to explain more:

Nicosia Études is a series of nine études in three sets, all composed in close partnership with the eminent violin virtuoso, Peter Sheppard Skærved. All études are composed as preparation for the upcoming “Nicosia Concerto,” a concerto for violin and string ensemble, also composed for Peter Sheppard Skærved. The last divided capital in Europe, Nicosia is an extraordinary city known for its history, architecture and diverse cultural landscape. Nicosia’s numerous workshops, including carpenters, metalworkers and coffin makers, and its open markets give the old town its distinct “soundtrack.” These sounds blend with busy roads, street coffee shops, and prayers from mosques across the border and dozens of languages and dialects spoken by the numerous ethnicities occupying its space. It is a place of contrasts, of barbed wire and contemporary galleries, a melting pot of cultures, ideas and ethnicities. All the above have inspired me to embark on this cycle of works as my personal way of paying homage to my city but also as a way of recapturing my own identity after emigrating for the second time. Another important inspiration for this cycle is the Manuscript Torino, Biblioteca Nazionale, J.II.9 (known as “MS. J.II.9” from the shelf-marking at the National Library of Turin, Italy, or as the “Cyprus Codex”). This codex is one of the most important collections of French mediaeval music and one of Cyprus’s most important cultural heritages. As a Cypriot composer, this collection has served as a constant source of inspiration in my search for my own identity. In terms of its musical legacy, MS. J.II.9 represents unique features amidst changing musical styles, and it was composed in the court of Nicosia, one of the last frontiers of Western influence at that time, close to the turbulent crusade regions. I have been working closely with violin virtuoso Peter Sheppard Skærved for over a decade now, and given our mutual interest in history, it seemed fitting for us to collaboratively explore aspects of MS. J.II.9 while composing a series of new works that are deeply rooted in the town of Nicosia

In the summer of 2018, I was in Nicosia with Evis, working on our shared project. Whilst his musical researches were taking him towards the Cyprus Codex, I found a dialogue between the stones of the City and to the astonishing poetry by troubadourices Llanguedociennes of the 12th and 13th Century, particularly Tibors d’Orange (born. ca 1130). As I walked around the vaults and stones of the lost French city, with Tibors’ poetry in my mind, the melodies and colours of what became my ‘4 Plaintes’ came into my mind. The first one was actually written in full walking around Bedestan/Chapel of St Thomas. I had never written anything remotely like these before, and am comfortable with saying that they have nothing to do with me.

Later the same year, my wife, the writer Malene Skærved, gave me an important gift, a volume of the complete solo violin works of the American poet Ezra Pound, who, working with his partner, the violinist (and early Vivaldi scholar) Olga Rudge, created striking violin pieces, using a very idiosyncratic but effective notation. Some of these are transcriptions of 13th/14th Century troubadour plaints and ‘dumps’, and some original works, but sited in a modern/medieval middle-world which strikingly counterpoints our explorations and creations.

I have been working with the American composer/pianist Michael Hersch for 15 years, after we were introduced by the great composer George Rochberg in Philadelphia. I collaborated very closely with Rochberg in the last 6 years of his life, and in his last year (he knew that he would not last long), he was determined to make Hersch and I friends and collaborators. Curiously, although, perhaps not surprisingly, the ‘blue touch paper’ of intense communication was only lit after Rochberg died. This resulted in a highly concentrated series of works, often responding to Hersch’s fascination with the most expressive/unflinchingly direct poetry and painting. So it is with these two cycles where Hersch was inspired by two writers, who stared in the face of tyranny and inhumanity in the 20th century. Instrument, player, and listener are pushed to the edge of expression and of comfort. Both works were premiered in spaces which resonate with a powerful sense of the extremes of human experience. I first played 14 Pieces at the Chleborád Villa, Leoš Janá?ek’s house in Brno, and …in the snowy margins… in the 12th century church of St Bartholomew-the-Great, in the Square Mile of London, where St Rahere founded the world famous hospital at the beginning of the Century.

Hersch also has very particular taste in visual art (visceral, expressionist, dark!), which directly informs how bow and left hand should approach the string: perhaps evoking what T S Eliot called the ‘circulation of the lymph’, in every gesture. There is a demand for ‘truth to materials’ at every moment, the sense that every note sings on the edge of, or even beyond, total collapse.

Gregory Rose is famously, a musical omnivore. As conductor and singer, his collaborations with figures such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage and Steve Reich are the stuff of legend (his recording of Stockhausen’s Stimmung, made 40 years ago, was celebrated recently with a sold out performance at London’s Barbican Centre. But Rose he is equally passionate about amateur musicians (he founded ‘Contemporary Musicmaking for Amateur-COMA) and campanology, particularly British ‘change-ringing’, and every year conducts enormous liturgical performances of classical masses in Sri Lanka, drawing audiences of many thousands. In the midst of all this, he composes at a furious rate. Last year I premiered his new violin concerto at London’s St John Smith Square, and in the middle of our preparations, he handed me this wonderfully enigmatic piece, The Dancing Fiddler.

The ‘Dancing Fiddler’ confronts the playfully dark side of the medieval mind-set, most particularly in Northern Europe. The walls of the churches and cathedrals of the Baltic, Northern Germany and Britain are filled with the ‘Totentanz’, the ‘Dance of Death’. [PICTURE]There’s a curious contradiction about many of these often-spectacular wall paintings, as, very often Death and his crew, are seen to bring just retribution, against the rich, the vain, and the tyrannical, and yet, at the next moment cuts short the lives of the young, the honest and the just. Death just drums on, or scratches on a fidel, or honks on a shawm, and the dance, our dance, goes on.

Posted on September 19th, 2019 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved