On Monday 19th August. I took the early train from Penn Station (NYC) to Washington, to begin a new project, one that I am very excited about.

The National Gallery of Art in Washington DC is one of the great museums. An important difference between the NGA and sibling institutions in UK, most particularly in the UK, is that the extraordinary international collection of great works pulls into a tight focus on the American schools of the last 150 years, in an international context, in stark contrast to the scattered collections in London. It host the longest running concert series of any museum, founded 78 years ago, in response to Myra Hess/Kenneth Clarke’s wartime concerts at the National Gallery in London.

Prior to my arrival at the NGA, I spent a lot of time exploring the collection online. If there was one piece which affected my thinking about the collection most from a musicians point of view, it was

Dorothy Dehner American (1901 – 1994) Music for Strings 1949

Looking at this reminded me powerfully of the effect which the work of Louise Nevelson (Dehner’s lifelong friend) has had on my music making. I was introduced to Nevelson’s work by the composer and artist couple Elliott & Deedee Schwartz. Elliott’s 2nd Quartet, which I premiered in London some years ago, was inspired by Nevelson’s work. A week after my trip to Washington, I found myseld uplifted by a wonderful Nevelson ‘Dawn Tree’ (1976) at sunset, in the sculpture garden of the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

So what am I doing here. When I start to work with any institution, this is a question which I like to keep as open as possible, for as long as possible {often frustrating my collaborators). Working with museums and galleries, only one thing is consistent in my approach, my work is never a concert in a museum.

This was on my mind as I walked down the hill from Washington Union Station, past the bell tower that commemorates President Taft, to the gallery. I was a little early, so I sat on the steps of the East Building, designed by Ieoh Ming Pe , and found myself looking at something familiar, but not. , one of Henry Moore’s ‘Knife Edge’ pieces. I was an admirer of his work from an early age, and somewhere, I have the rather over dramatic water colour of the single piece ‘Knife Edge’ on College Green outside the houses of Parliament. Context is everything: ‘Knife Edge’ in London, is constantly surrounded by the Fourth Estate, and these days, protesters. It means something very different there, from this most elegant placement, offering a sort of benediction to visitors. That, I noted, is what I feel about my work. It’s not marked out by much variety, but is profoundly affected, changed, by where I do it, and nowhere more so, than in museums. I have been lucky enough to work on longterm collaborations with the National Portrait Gallery, British Museum, Tate Gallery, Library of Congress, Galeria Rufino Tamayo Mexico City, Kunsthallen Bergen, Metropolitan Museum, Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum, and the Minneapolis Institute of Art, to name just a few. The answer to what business does music have in a museum, has always been a different one, for me.

I realised, that thinking about the NGA, my reponse, has from the first, to think about how music is referenced, represented and counterpointed, both in the pieces on show, and in the gigantic hidden collection, which can be explored online. If you go to the bottom of this post, you will see a short list of around 100 of these, ranging from ‘Allegories of Music’ through to Eakins’ ‘Pathetic Song’ (see above, which is about far more, of course, than merely a depiction of a performance of ‘The Lost Chord’).

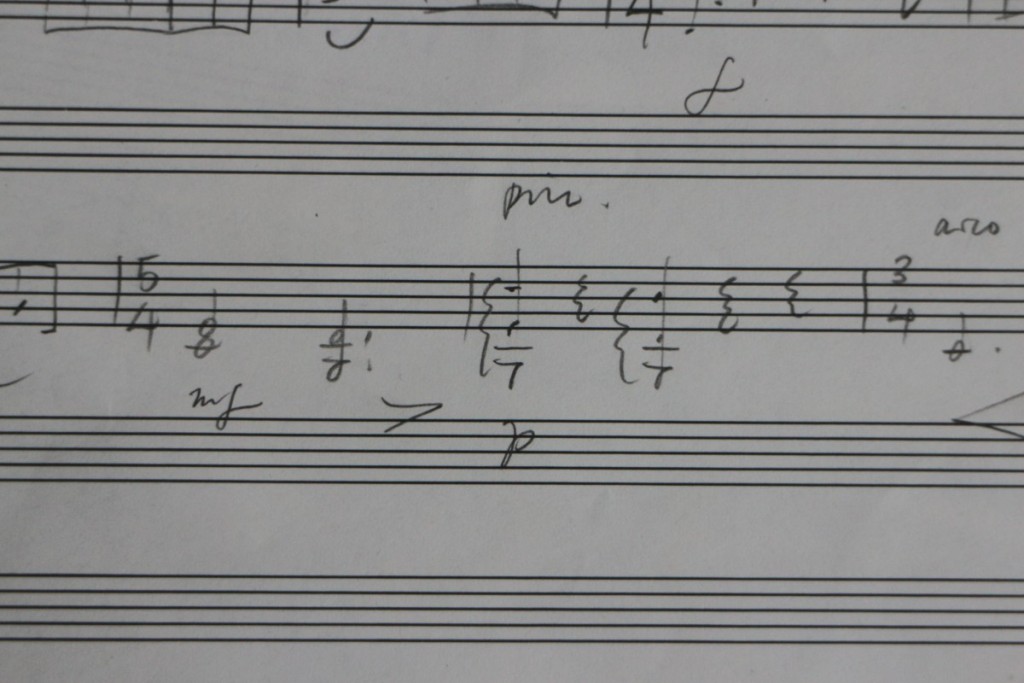

Musical instruments have been a favourite subject for artists, whether Cubists or Renaissance masters. The instrument which is depicted the most often in the collection been almost forgotten by the early 17th century today: the Lira da Braccia. You will find it in paintings, on medals, sculpture, all across the collection, but nearly always in the hands of a god. The piece below was written in the early 1600s, for the violin, as a reminder of what this instrument had sounded like.

Biagio Marini – ‘Capriccio for violin with three strings, in imitation of a Lira da Braccia’ ca. 1610 – Peter Sheppard Skaerved Violin

All through the Renaissance, the immortals were depicted, not playing instruments of the past, but rather, those of the artists’ own times. The Lira glimpsed in the astonishing Bellini/Titian painting above is recognisable by the two bass strings to the left of the fingerboard-the distinctive head is not visible as it is on the dozens of examples that can be seen throughout the galleries and in the collection visible online. It’s almost impossible, to escape the most dramatic Classical story of a contest between wind and string players, the myth of Apollo & Marsyas, which can be seen on the dish above. I will return to this later. But for now, lets turn to vibrating strings.

Pierre Legros I (1629 – 1714)Cherubs Playing with a Lyre 1672-1673

To my delight, I found this sculpture on one of the fountains which stand in the Garden Courts of the West Building. This is from the height of 17th century carving, of voluptuous excess in marble, of the extraordinary meeting of all the arts in the 7 decades of Luis XIV, ‘Le Roi Soleil’. Looking at the piece, I noticed that the two putti are playing with a ‘Lyre’, specifically a Cithara, the instrument favoured by Sappho, Apollo, and depicted in use as late as the 9th century, in the Utrecht Psalter, drawn by an Anglo-Saxon artist in Reims. Last year, I had a slightly terrifying experience, playing Bach’s Ciaconna ‘to’ an ‘Apollo Citharoedus’ in the Cyprus Museum. This was a powerful reminder that for the Greeks and Romans, such objects possessed enormous power: halfway through the performance, I had what I can only describe as a ‘Mary Renault’ revelation (if you have read her ‘Mask of Apollo’ you will know how frightening this could be), a realisation that I was messing with something dangerous, beyond the human. All art has this potency. We sometimes forget that it’s there, but performance, ‘doing stuff’ in dialogue, in counterpoint, even as an offering, with and to the work, can activate these qualities, even perils, in extraordinary ways.

But back to the Legros: I won’t explore the complex contra-symbolisms of this piece, except to point out that this sculpture once had working pegs, and strings, one of which is still hanging to the right. They were originally affixed to a the ‘yoke’/’zugon‘ formed by the shell which makes a hat for the Neptune-like head at the bottom of the instrument. This is a 17th century sculpture, made at the height of the age of the Viola da Gamba in France, the glory days of Marin Marais, de Machy and St Colombe, so it’s not suprising to find that the sculptor has given the soundbox of the cithara gamba ‘C-shaped’ sound holes. Here’s a minuet by de Machy

Le Sieur de Machy-Pièces de violle (1685) – Minuet

Peter Sheppard Skaerved – Tenor violin (Barak Norman ca.1700)

That’s a brief taste of the music which is, broadly equivalent to the sculpture; it’s worth noting that the composers of polyphonic music for the gamba succeeded in dethroning the the lira da braccia and the lute, previously thought of as the instruments of the gods.

But there’s a deeper question which springs from this sculpture, and one which resonates, vibrates, if you like, down to our time. What is it supposed to DO? These might seem a strange question to ask, as until recently, we were living in an age of plastic art, silent in white spaces. But this was not always the case, and certainly not in t of the age of Legros and Louis XIV. The first clue, is that it was, and still is, part of a fountain. In his monumental ‘Landscape & Memory’ (1995), Simon Schama wrote about the fountains of the princely courts of baroque Europe. These were not, he pointed ou’t places, of gentle curtains of spray in the morning sun, but theatrical, noisy, scary, funny, and even dangerous places. Most importantly, fountains were designed as noisemakers. In the gardens of the 17th Century Rosenborg Castle in Copenhagen, a bronze lion is concreted into the top of a gate post. If you reach up and put your hand into his mouth, you will find the that tongue moves, and rattles. Look carefully, and you will see a row of holes along the tongue, so that the lion can spit water while it rattles and roars. This is the nature of 17th century statuary, and means that we have to either presume that Legros’ putti and lyre made a noise, as water sprayed the four strings (in ‘Aeolian harp’ manner), or that it was expected that one would brave the water and strum the strings, or that the viewer was expected to think about what noise it might make, were it to be played, presumably by a god. Or all three. Now look at this:

The work of the sculptor Barbara Hepworth, is particularly close to my heart, and informed how and why I became a musician. My father was evacuated to St Ives, Cornwall, during the Second World War, where she, Nicholson and the potter Bernard Leach had established the community of modernist artists that sings on by the Atlantic to this day. There was a certain amount of ‘aggro’ between her and Henry Moore about which of them first pierced a sculpture: but one thing is for sure – it was Hepworth who followed up the piercing with stringing, as seen above in the example above, which was conceived in St Ives. Hepworth sought out the model of music for her work. She said, to the composer Priaulx Rainier:

Hepworth to Rainier: “I am thinking about music as being the life of forms.”

And, for myself, I feel the same, but in reverse. Here I am, practising in her Trewyn Studio in St Ives.

Hepworth was fascinated with music, in particular with the composer Bach. “In Bach,” she wrote, “the visual sense is always delighted, because every movement is beautiful. All the bows make lovely rhythmic movements, a lovely vision.” She would have loved the idea of her sculpture in this museum. Writing about the artists and musicians in St Ives:

‘We all felt the fast growing understanding of art around the world and the international language which had been created-we may have lived at Land’s End but we were in close contact with the whole world./Looking out from our studios on the Atlantic beach we became more deeply rooted in Europe; but straining at the same time to fly like a bird over 3000 miles of water towards America and the East to unite our philosophy, religion and aesthetic language.’

Hepworth’s deepest collaboration, in my opinion, of far greater importance than the work with her husband, Ben Nicholson, was her friendship with which the trail-blazing, South-African-born composer, Priaulx Rainier. It’s worth noting that Rainier was a powerful influence on generations of composers in the UK: Britten and Tippett were profoundly affected by her work. But perhaps only Hepworth could see deep into its true nature. The strung sculpture in the NGA is directly analogous to Rainier’s output at the time.

Priaulx Rainier-Movement (‘Incantation’) for Piano and Violin 1935

(Peter Sheppard Skaerved -Violin, Roderick Chadwick -Piano)

Not for a minute, am a suggesting that Hepworth’s strung form ‘sounds like’ Hepworth’s near contemporaneous sculpture. But it is worth reminding ourselves that music is not about what it sounds like, any more than sculpture or painting is about what it looks like. It might be simpler to say that their essences come from a shared place, or that they have natures which are similar or analogous. Words fail at this moment. T S Eliot was writing his Four Quartets at the time that Hepworth conceived this sculpture. I think that it helps.

Only by the form, the pattern, / Can words or music reach / The stillness, as a Chinese jar still / Moves perpetually in its stillness. / Not the stillness of the violin, while the note lasts, / Not that only, but the co-existence, / Or say that the end precedes the beginning, / And the end and the beginning were always there / Before the beginning and after the end. / And all is always now.’

For me, when I see a tightened string or wire, on a sculpture, on a musical instrument, or even on a suspension bridge, I am fascinated by the idea of what it might sound like, if I were to stroke or pluck it. There’s a power in the interdict against touching, inasmuch as it prevents disappointment (I have strummed a strung Hepworth in private hands, and wish that I hadn’t!). From the poetic point of view this can reach in many directions. Eliot, was, of course referencing the most famous poem about (yes I know it’s about far more) a silent object, William Wordsworth’s Ode on a Grecian Urn, which will be 200 years old in 2020.

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone:

The power of the Eakins Singing a Pathetic Song lies, in part in the fact that each of us imagines that the singer has sung, or is about to sing, something different. She is clearly not singing, whilst the accompanying cello and piano are working away, so we are either in the prelude, postlude, or between the verses of a strophic song. Eakins has included his own Wordsworth-ean joke, not only are we imagining ‘unheard’ melodies, but he too pipes ‘ditties of no tone’.

But there are not only ‘strung’ sculptures in the NGA: there’s at least one example of a strung painting.

This piece caught me by surprise. Guitars were an idée fixe throughout Picasso’s output, but this example, from 1926, asks more questions than it can possibly answer. It’s a collage, of wallpaper, carpet tacks, nail, paper, string, and charcoal on wood. Unlike Hepworth’s sculpture, from a decade later, which a viewer might imagine having some aethereal tone, Picasso has done nothing to suggest any other sound than ‘thud’. 5 of the strings of the putative guitar are presented by one piece of twine wound around seven nails. Two more are suggested in charcoal on the paper. This is both a conceptual guitar, or the poor man’s guitar. It’s almost as if he has determined on finally breaking the spirit of his ‘Old Guitarist’ (1903) which can be seen at the Art Institute of Chicago. Or maybe he wants us to have to reach into or imaginations, and come up with a different guitar, even a lyre, Apollo’s instrument. The painting is not about what the painting is about. Whilst this was the period in which Picasso had been famously claimed by I the Surrealist André Breton s ‘one of ours’ in his article Le Surréalisme et la peinture, it’s clear at least in this assembly, that Picasso was far from leaving behind his collaboration with Braque, and, at least to me, that there was a slight leaning towards the radical understatement of the artistic communities in the orbits around Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, Olga Rudge, George Antheil and Virgil Thomson. This is just me, I know, but I hear something of the extreme simplicity of means and aim that can be heard in Thomson’s contemporaneous musical portraits. He would ‘do’ Picasso in 1940 (to the artist’s scorn). Here’s Gertrude Stein as a Young girl.

I am not saying that this is ‘right’. It’s just what Picasso has me thinking, right now! There’s spectacular sculpture of a guitarist which caught my eye, and my pencil: see below. Jacques Lipchitz’s 1918 bronze plays, wittingly or not, with the problem of monumentality which can assail the representation of music.

One of the first things to catch my eye, in the East Wing of the building, was a tiny detail, in the wonderful 1924 Pianist and Checker Players by Henri Matisse. This is such a prosaic detail, but one which immediately sparked a conversation, about the possibility of including György Ligeti’s Poème Symphonique for 100 Metronomes (1962) in one of the presentations in the gallery-it would work wonderfully in the atrium which you can see above. But this is what set me off:

I hadn’t noticed the metronome on the top of the piano, in Matisse’s Nice apartment, played by his favourite model Henriette Darricarère.

It seems a natural thing, to take a pastoral interlude, like the Scène aux champs in Berlioz’s symphony. One of the most astonishing pictures, even grandest, in the gallery depicts the most humble subject – a country fiddler.

The picture is so monumental, that was not able to find a place in the room to look at it comfortably. To be honest, the best option would have been to stand on the couch in the middle of the room. But I had a feeling that the museum guards and the group of tourists who were taking a well-earned rest from art-gorging on it, might not have been best pleased with me if I had have done that. I have been searching for what it is most strikes me about this portrait. And I think that what I have come up with is a sort of memory, a memory of enlightened dignity. On the train back from Washington, I read the first book of Anne Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho (1794). Throughout the book, the image of music in the countryside recurs.

‘…resting upon a cliff of the Pyrenees, she heard from below the long-drawn notes of a vioin, of such tone and delicacy ofr expression, as harmonized exactly with the tender emotions she was indulgint and both charmed and surprised her.’

P.161 ‘The Mysteries of Udolpho’ Anne Radcliffe. 1794, Penguin, London 2001

I know that it’s going to take me a while to bring this, musically, into the decade in which Manet painted the ‘Old Musician’. But what needs to be said is that the middle of the 19th century marked a watershed in the understanding and perception of what we might, today, talk about as roots music. In the 18th and early 19th century, riding in the wake of the cult, if you like, of ‘nature’ which resulted in the poetry of Wordsworth, the pioneering proto-ecological writing of Gilbert White of Selbourne, the work of Mary Anning, and Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, not to mention the work of the Hudson River School that can be seen in the NGA, there was the beginning of a genuine interest in the actual music made on the land, distinct to the music which the artistic elite imagined was heard there. In the salons of the 1780s, Nature had been all the rage. Queen Marie Antoinette herself was in the forefront of applying this notion to fashion, and behaviour, and it was not long before the same notions began not only to liberate the dress and movement of women, but also the deportment, and even the training, of performers. It would have been inconceivable for the performers onstage, whether dancers, actors, and musicians, to have retained the stiff, corseted, bewigged, manner, when there audience were deporting themselves naturally. Gradually, though certainly driven by the revolutionary, in their way, innovations of salonistes such as Emma Hamilton and Viotti, idealistic fresh air began to blow through the corridors of power. Of course, these would blow stronger and stronger, and the gentle zephyr which such as Marie Antoinette had hoped would accompany her activities blew up into the ‘howlings of the tempest’ noted by Madame de Hausset.

J J Rousseau -‘Ranz des Vaches’-Arr. by Pierre Baillot from J J Rousseau ‘Dictionnaire de Musique’ -Peter Sheppard Skaerved, Violin

Rousseau had advocated a new kind of virtue, the ‘sublime science of simple minds.’ His fellow composer, André Erneste Modeste Grétry (1741-1813), whose admiration of Rousseau knew no bounds, expressed how this ‘sublime science’ might offer an ideal for melody:

“…if there is too much learning in music, and too many complications in the accompanying parts, the melody-which is the main point of this art-is destroyed. I would much prefer unaccompanied song (if it is good) to [song] accompanied by many orchestral parts that smother it and make me search for it as a diamond lost in the brushwood.”

Eventually, these refined imaginings of what country musicians might, or perhaps should, do, would morph into a genuine interest in what they actually did. This, to us logical, innovation was driven from Scandinavia, where the ‘Flaxen Haired Paganini’ Ole Borneman Bull who had drawn mass public attention to the Hardanger-violin virtuoso ‘miller’s son’ (‘Myllarguten’), whose actual name was Torgeir Augundsson (1799(?)-1872), who he met for the first time sometime between 1829 and 1831. This was the beginning of a revolution the public understanding of folk music, and the first true documentation of what it sounded like.

Myllargytten – ‘Gangar’ (free version by PSS 8 8 16)

I can’t get away from a slightly queasy feeling, alongside my wonder at this picture, which often attends looking at Bartolomé Esteban Murillo’s paintings of street children. He invites us to view, to enjoy the poverty of the children, without any sense that there was a duty to ameliorate it. I know that this is nonsense: I can’t make a 21st Century pronouncement on 17th Century mores. But it’s there, and I confess that I am far more comfortable with Murillo’s work which eschews this particular voyeurism, and where I can luxuriate, and that is assuredly the word, in a clarity that can rival his contemporary Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez’s. The kindly, yet piercing scrutiny (of me/us) of Manet’s violinist, is matched by Murillo’s so-modern girl in the window.

Manet’s terrifying clear eye does not strike me as a compassionate one; one might argue that the very power of his work is that he does not commentate, but draws the viewer into the the picture so fast, that they are complicit before realising what they might be complicit in. It’s certainly the case with ‘Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe’, which Manet painted in the same year as this group. In the case of the violinst, there’s a question of performance. How shall I put this? Who is the audience? Has the violinist just finished playing for the very young mother, two children and two adults, or are they being presented as a frame for him to play for us.

The art historian Simon Shaw-Miller alerted me to the idea that certain pieces of art are what he calls ‘provisional’, that they are waiting for something to happen – that is that until they are experienced, or activated, like a musical score, or instrument, or the machineries which Paul Klee invites us to observe, the art itself is dormant. One might say that this is the case here. There are many hints of things which have just happened, or are about to happen. The violinist is clearly a visitor, a traveller. That much is clear from the bundle at his feet, almost falling out of the frame. He’s also hirsute, his salt and pepper beard pointedly bushy by comparison to the neatness of the young blade perched up on the right. And he’s also darker than anyone in the picture; implying that 1. He’s spent a lot of time on the road 2. He’s portrayed as either the racial stereotype of a gipsy, Romany, Zigeuner, what the French call Tzigane, or as being Eastern: Balkan, Turkic, Arab,

So he’s either about to play, or to leave. Whichever is the case, whatever the varying curiosities of the children and adults around him, he does not belong. The question is, of course, whether or not we are invited to feel awkward about their, our curiosity/alineation, or whether Manet is simply offering him, like the ragged young girl with the baby, for our curiosity.

Of course, the romance of the strolling musician was well chewed over in the 19th century. Gilbert and Sullivan managed to make a fascinatingly oblique joke about the cliche in the character of Nanki-Poo in The Mikado (1885), ridiculing the contemporaneous rose-tinted view of the medieval age by transplanting it to Shogun Japan.

A wandering minstrel I —/ A thing of shreds and patches /Of ballads, songs and snatches/ And dreamy lullaby!

And of course, the fascination with ‘otherness’ found its way into the music of the 19th Century, riding in on the back of the nationalistic fervour attendant on romanticism. Composers found particular amusement in what we would now call ‘cultural appropriation’, and even today, we play the Spaniard Pablo de Sarasate’s Zigeunerweisen (his only work with a German title), and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane without asking the questions that Manet might be waving at us.

But now, I would like to return to the rural idyll. Here’s another ‘ranz des vaches/cow call’, which I like to imagine that this wondering vioinist might have like to play for himself, out on the road. It was written for me by the great British composer David Matthews.

David Matthews – D Major Prelude Op 132 No 15 ‘Monte Maggio’

Peter Sheppard Skaerved – Violin

https://open.spotify.com/track/73gUpce4tH7soWIJ9dGWD7

Let’s leave the great outdoors, and return to the world of the ‘salon’, the environment where Thomas Eakins’ singer, above, is so hard at work. Here’s part of a portrait, one of several in the NGA by perhaps, my favourite portraitist, an artist who spent her life close to performers, and was particularly close to one of the great violinists.

The Marquise de Pezay, and the Marquise de Rougé with Her Sons Alexis and Adrien

(1787)

Élisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun had, or to me, has the most extraordinary gift of any artist, the gift of joy. She brings joy to the viewer of her paintings, as she clearly brought joy to everyone around her, and to nearly all of her subjects, judging by their faces. We know that she loved to paint in company, and indeed, in every city which she called home in her itinerant life, she gave salon evenings in which she would paint, whilst the greatest musicians of the day played music, and the great and the good squeezed into be part of the extraordinary atmosphere which she created. Here she is, describing how music should be part of a meal.

“Beautiful, good, harmonious music should be heard during a meal. The musicians placed above the diners on a large stage. I am of the opinion that…it is the most charming thing to hear music while one is at table. It is only thing that I would wish were I to become a very grand lady…or extremely rich-for I prefer music to all the silly chit-chat of people eating.”

(Tom. 1, Pp.330-1) Vigée-le Brun Diary

If there was one musician with whom she identified the most, it was the greatest of all violinists, Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755-1824). She first encountered, Viotti, her exact contemporary, at the salons given by her father in Paris is pre-revolutionary Paris. Later, they resumed their friendship in London, where Viotti had fled in 1790, most likely as the result of his close association with the Marie Antoinette, to whom he seems to have been in service in the mid-1780s. Here’s his ‘Suonata’, in a performance which I have ten years ago at the Library of Congress.

Giovanni Battista Viotti – ‘Suonata in 2 parts, both parts to be played by one player. Peter Sheppard Skaerved – Violin

It is reported that when Élisabeth-Louise gave salon evenings at her tiny lodgings in London, at which Viotti would play, there would be so little room, that the Prince Regent, George, who was a terrific enthusiast for music, had to squeeze under the fortepiano.

Tragically, the extraordinary portrait Élisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun painted of her dear friend was lost at some point in the 20th Century-this black and white photo is all that we have.

I think that a museum environment like the NGA demands that we do all that we can to evoke the atmosphere of the salon. Vigée-Le Brun’s salons included the most extraordinary thinkers and artists: she and Viotti were, at various times, joined by minds such as Cherubini, de Stael, and Stephanie de Genlis. We need to come up to the standards of art, ideas and inspiration which flowed with the wine (and in England, Tea, of course) at such events, and allow them free voice in our own time.

And the most important aspect of such events, should be the spirit of joyous friendship. Here’s Elisabeth Vigée-le Brun’s farewell to Giovanni Battista Viotti, after his death sums this up, I think beautifully:

“My God, how I wish you could be with me so that I could listen to him speak, with so much expression on his face, and the sweet sounds which I so loved hearing. Why do I not hear them anymore! They are still in my heart, and I continually say to myself Encore, Encore”.

It’s that depth of feeling and directness of expression which I find in all of her painting, and her diaries (which have never been translated into English).

But here’s another kind of salon, and one, which I am for all sorts of reasons, I am much more familiar with. Whistler, famously, used the model, the idea of music, as inspiration for painting. His most famous work, most commonly known as ‘Whistler’s Mother’, has a title which hints at this Arangement in Grey and Black No.1′, whose musical origin comes clearer when one turns to the other picture of the young woman in the picture above, Joanna Hiffernan (1843-1904) , which also hangs in the NGA ‘Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl 1862’. I will return to this ‘idea’ of music as a model for painting later.

But the main reason for my turning to ‘Wapping’ is that this picture, depicts the Thames a few metres from my front door. In fact, the painting does not depict a room in Wapping (which is about 10 minutes walk east of Tower Bridge, London), but the view of that beach from the other side of the river, Bermondsey, in the Angel Pub, which still stands. If I walk out of my front door, in the cobbled dock streets of Wapping, and walk to the iron ladder at the end of the lane, I will be standing on the foreshore which which you can see behind Joanna Hifferman, in about 2 minutes. Here’s the view from my side of the river.

Naturally, I identify with the people in the painting. My family has worked on this bit of river for hundreds of years, and its right near the place where I have lived and work for most of my own life. There’s a simple point here: when we walk into a gallery, finding something which we find familiar is where most of us start. I certainly think, that for me, finding a midpoint between Whistler’s working-class (my people) tavern conversation and Le Brun’s rather more refined gatherings, is something which I want to hunt for in this exploration, this process. Just a sidebar. If I walk out of my front door, and turn away from the river, in one block, I come to the ‘Old Star’, the pub owned by JMW Turner’s landlady and partner, Mrs Booth.

I hope that I will be forgiven, if I turn just once more to the close friendships that that can blossom between artists and peformers. This washed over me, when I found myself enchanted by this Thomas Gainsborough.

I have a particularly affection for Gainsborough’s pictures of working people, in the countryside, or, as here, on the seashore. As a child, I loved the illustrations of Edward Ardizzone (1900 -1979), and it was only later, that I came to realise how deeply he had been influence by Gainsborough’s figures such as these. Anyone who has read ‘Tiny Tim and the Brave Sea Captain’ will recognise what I am talking about. But what this most calls to mind, is Gainsborough’s great love for the Gamba-player composer, Carl Friedrich Abel ( 1723 – 1787). I need do no more, to illustrate this, than to show the sketch of the composer made in 1765. Abel died the year before Gainsborough: the artist was inconsolable.

When I curated the exhibition ‘Only Connect’ for the National Portrait Gallery in London, this picture was central for me, illustrating, perhaps better than any other, the deep links between canvas and bow, between charcoal and musical instrument, between artists.

Walking around Minneapolis a few days ago, I picked up a copy of Dumas Malone’s multi-volume biography of Thomas Jefferson. The volume charting Jefferson’s Paris years (‘Jefferson and the Rights of Man’) took me back to the Virginian’s intense relationship with the artist/composer/harpist Maria Hadfield-Cosway. This was very much the intense communication which can be fostered in the salon, and in their case continued in letters. They talked, they played music together, walked, and in Jefferson’s case ill-adavisedly tried to show off his athletic prowess (he broke his wrist). They even had a theme song, from Sacchini’s opera Sardanus. Appropriately, the aria they chose, was ‘Jour Heureux’ (Happy Day). Two centuries later, their discussions, their friendship became the inspiration for a violin concerto which the great American composer Elliott Schwartz wrote for me. Here’s a live performance.

Jefferson and Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun moved in the same circles-the picture above, The Marquise de Pezay, and the Marquise de Rougé with Her Sons Alexis and Adrien , was shown at the Paris Salon of 1787, a few months after Jefferson wrote his famous letter to Cosway, ‘The Heart and the Head’, which is to their friendship as the ‘Heiligenstadt Testament’ is to Beethoven’s music (the core). I like to imagine what happened when they met. As I left the West Building of the NGA, I found myself looking into the eyes of the Virginian many years later, in the magnificent study by Gilbert Stuart ( 1755 – 1828 ), painted 5 years before Jefferson’s death. I like to think, that whatever I can do at the Gallery, will aspire to the standards of interart communication set by these extraordinary people.

The List

Prior to being able to spend time at the NGA, I was able to do a number of deep dives through the collection, now viewable in almost its entirety, online. Over the last 15 years, all our lives have been revolutionised by the ability to access, and explore vast amounts of material online, and nowhere has this been more revolutionary than in museums and galleries. Collections which were only available with special permission, waiting for hours, sometimes even days, are now open to all of us. The big question is how we choose to use these facilities – or, perhaps more to the point, how to really find something meaningful in the sheer embarrassment of riches which is available at all hours, from phones and computers.

I purposely took the slow train from New York to Washington, allowing my self to deepen my engagement with the collection before I ‘met’ it for real, and as you can see from the annotations on the printed list on the table above, this led to a lot of discoveries-yet to be added to the simple list of pieces below. At the moment this list is very crude, but works as an ideas resource. I will add some commentary.

Master of the E-Series Tarocchi Ferrarese – Musicha (Music) c. 1465

Probably Venetian- Allegory of Music c. 1500

Albrecht Dürer – The Holy Family with Five Angel (musicians) in or before 1505, Thyrsis & the Goatherd

Milan Majolica – (1500-50) ‘Apollo & Marsyas’

Lucas van Leyden -The Musicians 1524 [domestic joy in music making]

Heinrich Aldegrever -Three Musicians (1551)

Zacharias Dolendo – A Veiled Woman with Two Musicians Playing a Gridiron and a Bellows 1595/1596

Gerrit van Honthorst – The Concert (17th Century)

Nicolaes Lauwers/Gerard Seghers – (1620) Saint Cecilia Accompanied by Heavenly Musicians

Hendrick ter Brugghen-Bagpipe Player 1624 [wonderful profile]

Judith Leyster -Self-Portrait c. 1630 (painting a man playing the violin)

Rembrandt van Rijn- Man with a Sheet of Music 1633

Adriaen van Ostade – Wandering Musicians ( 1642)

Johannes Vermeer – Girl with a Flute probably 1665/1675 [a recorder big Van Eyck possible]

Donato Creti –(Bolognese, 1671 – 1749) Musician and Dancing Figures

Giuseppe Mazzuoli – A Nereid c. 1705/1715 (link to Michael Alex Rose (Naschville) ‘Diaphany’

Hogarth – Enraged Musician (1741)

François Boucher – Allegory of Music 1764, Delightful Sketch

Balthasar Anton Dunker-Musicians Traveling through a Forest c. 1780

Ludwig Emil Grimm – (1826) Preparing to Play the piano

Gustave Doré -Dwarf Musicians of Granada (1861/1862)

Edouard Manet – The Old Musician (1862)

Moritz von Schwind Austrian- Maria Theresia Embracing the Young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart c. 1864 [the Schubert link]

Oliver H. Willard-Cavalry, Musician (1866)

Mariano Fortuny y Carbó-Standing Musician (1870

J M Whistler – (1875) The Piano

Thomas Eakins – (1881) Singing a Pathetic Song

Paul Gaugin – (1884-8) Man playing the Piano

Walter Twachtmal – (1890) Winter Harmony

Whistler – The Duet, Symphony in White [Link to Symphony in Black & White-Sarasate in the NPG]

Charles Fromuth – (1897) A Dock Harmony-Fishing Boats

Bonnard – (1898) Artist’s Sister and Children at the Piano

Anon (x2) – 1900 Woman/Man at Piano plus Ghost

Jean-Louis Forain – (1900) At the Piano

Albert Besnard – Musician (Musicienne) (1900)

Gorky – (1904) The Plough & the Song

Carlo Carra – ‘Graphic Rhythm & Homage to Blériot’

Takahashi Sh?tei – (ca 1910) Figure Watching Two Musicians in a House

Boccioni – (1912) Music Futurism

Marc Kandinsky – ‘Uber das Geistige in der Kunst’ (1912)

Raoul Dufay – (1912) ‘Music and the Pink Violin’

Max Beckmann- (1913) At the Piano

Max Beckmann – Saengerin vor Fluege (mis-translated)

Georges Braque – (1913) ‘Aria de Bach’

Albert Belleroche – (1914) The Artist’s Mother at the Piano

Ernest Rovert – (1914) At the Piano

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner – Composer Klemperer 1916

Modigliani- Café Singer 1917

Picasso – (1917) Still Life. (Guitar/MS)

Marc Chagall –Musician (1922)

Picasso – (1922) Harlequin Musicians,

Otto Dix German-Otto Klemperer 1923

Andre de Segonzac- (1927) Clown at the Piano

Muirhead Bone – (1927) Joseph Conrad listening to music. (1901) Tea and Music

Georges Braque – (1928) Still Life/Table Music

Stieglitz – (1922) Music cloud photos

Matisse- Pianist & Chequer Player ( (1924)

Kathe Kollwitz – (1925) ‘Prisoners listening to Music’

Paul Klee – ‘Tree & Architecture’

Beethoven Portraits – Hugo Gellert, Adolph Bellocq (1927), Henry K. Gleichenstein

Grant Tyson Renard – (1930) Woman at the Piano

Bernard Kuhn – Inescapable Rhythm

Stuart Davis – Barber Shop Chord 1931

Max Oppenheimer – (1932) Rosé Quartet [mislabelled]

Raymond Jonsonpainter – Variations on a Rhythm–U 1933

Albert Potter-(1933-1936) Modern Music

Mark Rothko – Untitled (musicians) (1935)

Hale Woodruff / -Blind Musician 1935 (published 1981)

Walter Drewes – (1934) ‘Composition & Dynamic Rhythm’

Mark Rothko – (1935) String Quartet. (1936) Music

Escher – (1936) Mathäus Passion

Dorothy Milne – (1938) String Quartet [women]

Donald Carlisle Greason-Igor Stravinsky Conducting (1940) Series-amazing

John M. Socha- Winter’s First Symphony c. 1940

William H. Johnson – Street Musicians(c. 1940)

Carl Burgemester (1940) Piano Cover NB: Index of American graphic design Full of instrument designs

Harold C. Swartz- Symphony c. 1940

Edward Landon- Counterpoint 1942

Max Ackermann – Music of the Spheres 1944 [don’t forget bizarre musical recordings with Asger Jorn]

Karl Baum – (1944) Impressions of Wagners Music

Joseph Solman – (1945) Mozart series

Mark Rothko (?) Woman playing piano

Jean Dubuffet – (1946) Music for Edith [Piaf]

Max Cohn – (1946) Quartet

Ellsworth Kelly – (1949) Music

Charles Sheeler- Counterpoint 1949

Seymour Tubis- Old Musician (1949)

Dorothy Dehner – ‘Music for Strings’ (1949)[I think that this is the painting that has influenced me most on this short excursion, and I found the reminders of Louise Nevelson (not in the NGA) and her musical notions irresistible)

John Cage – (1950) ‘Music Walk’, (1973) ‘Composed for Merce Cunningham’

Ben Shahn – (1950) ‘Silent Music’

Ruth Leaf –Musicians (early 1950s)

Billy Morrow Jackson – Duet c. 1953

Luigi Lucioni – (1953) Tree Rhythm

George Schreiber – (1954) ‘Musical Interlude’

Krishna N. Reddy –Musician (1957)

Joan Mitchell – (1958) Piano Méccanique

Larry Rivers – Stravinsky II 1966 Series

Luigi Lucioni – (1961) Rhythm in White

Feldman – (1967) String Quartet rehearsing in the NGA

Marc Chagall – (1969) ‘Orphée’ (mosaic)

Allen Ginsberg – Various annotated photos, referencing music [Brahms Sextet]

Robert Frank – (1970)’ A Music about me’

Francesco Clemente – (1981)

Larry Rivers – (1990) ‘String Music at Carnegie Hall’

Marc Chagall – (1990) ‘The Musician’

Joan Cassis- (1992) Sheron with Piano

Robert Rauschenberg – ‘Bachs Steinen’, (1994) ‘Music’

Richard Tuttle – Music 1995

Posted on August 20th, 2019 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved