Pietro Nardini (April 12, 1722 – May 7, 1793)

110 Capric[c]i – A day by day exploration (audio will gradually appear)

Book 1 No 45 G major

It’s been a few days since I was able to spend a night with the violin, having a conversation with Nardini. Recordings, and rehearsals loomed, and other composers, from the 21st, 20th and 18th Centuries, demanded my attention. Firstly I can report back that the Nardini’s technical and musical demands, the effort to understand his ‘school’ if you like, is paying off. I find myself thinking about the great lost Lincolnshire violinist ‘Thomas Linley II’ (1756-1778), who was lamented by Mozart as a genius cut off before his time. He was not only Nardini’s student, but his chamber music partner: when Charles Burney was travelling in Italy in 1770, he heard master and student playing together many times. What would the benefit have been for a true British violin school, had Linley lived, and maybe been in the UK when his near-exact contemporary, G B Viotti, arrived in the 1790s. They were both, in different ways, devotees of Tartini. The meeting could have been explosive, or joyful. Studying these studies, gives me the chance to be a little boy in Nardini’s school.

But, today, I would like to talk about models. Last night I spent time with rather charming ‘fugato’ – caprice, no 45, from book 1. First of all, a note on reprises/recapitulations. Yes, I know that this is not sonata form, but some of the elements were in place by the 1750s and one might argue that ‘fugal recapitulation’ has much to do with the eventual ‘triumphal return’ notion which would, perhaps, be brought to its height (or its knees) by Beethoven. My favourite example in the ‘canonic’ violin repertoire, is the C Major Fugue from the Sonatas & Partitas of Bach, where the recapitulation is pre-empted by an enormous ‘fake’ return, in the dominant, of the theme, upside down – which means that when Bach brings the them back, in the tonic (finally) he’s got to do something special, which he does, with (briefly, and somewhat disingenuosly) a fake double fugue – the first entry is adorned, and encumbered, with a descending chromatic countersubject. It’s fantastic, brilliant, and mercifully, unsustainable (it only lasts until the second entry). There’s really no excuse for it!

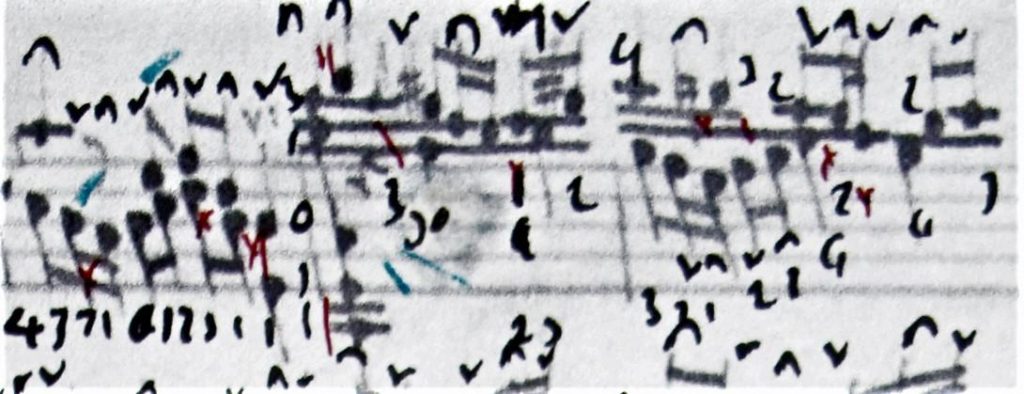

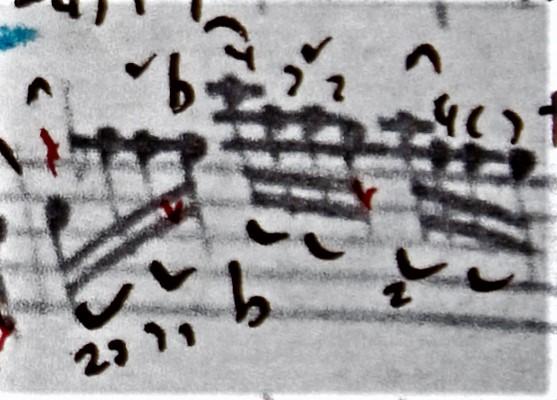

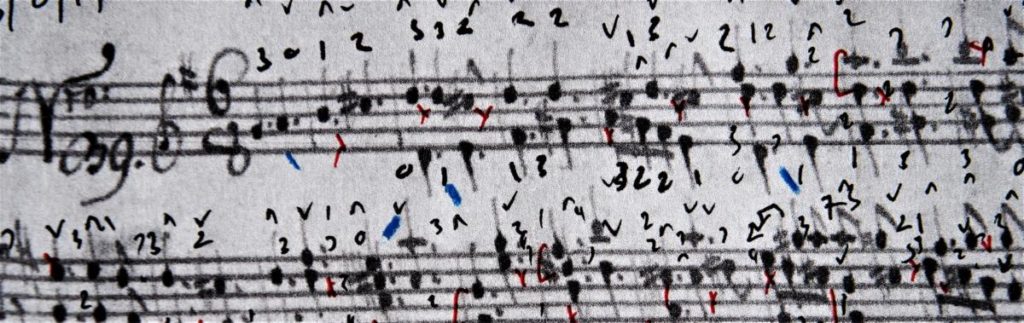

This is simple by way of noting that there was an established practice, of enhancing the impact of the tonic return, with a little misdirection, and Nardini offers an example here. Here’s the opening, with its three bar subject.

And here’s the return, at the end of a very venetian arpeggiated sequence.

Note that the moment of return is also the peroration of a tension-building sequence of arpeggios, which is released with the GDBG chord. Instead of drawing the opening two notes of the theme from that, which would necessitate GGBG (which Bach might do), Nardini appropriates the descending figure from the second bar of the ‘answer’ (see bar 5) and uses those to slightly wrong-foot listener and player…and then they realise where they are in the second bar of the return. Brahms pulls a similar misdirection in the recapitulation of the first movement of his G Major Sonata Op 78. But now for something prosaic.

I am convinced that this magisterial MS was written out for the composer’s own use and mnemonic. Consequently, there is a degree of information missing, particularly when it comes for the modelling of harmonic sequences. The first two lines offer and example of the composer setting a model and then continuing harmonically, whilst keeping the score light, by not writing out the model, the ‘how to do it’, again and again. You have to look a little hard to see it, but now that I comfortable with Nardini’s ‘shortcuts’, this one is obvious. Bars 8-9 solve the problem of how to play the sequence from 11-13 without losing the intensity by having to release the held minims or slurring the material

However, later in the piece, Nardini fails to offer a model, most likely, because he knew what he wanted to do, because it was, if you like, so sui generis, a sweeping set of broken chords. Here’s the spot.

My instinct, upon looking at this for the first time was that his should be sweeping arpeggios, like the Locatelli ‘Labyrinth’. But at the moment, I am not sure that this right. Has Nardini offered a model with the middle semi-quaver section? Or would using that model make the piece too samey, monotonous, distract from dash and elan of the ending? At the moment, I don’t know enough to say. Let’s keep the question open!

Book 1 No 11 A Major Fuga

This fugue gives me an opportunity to talk more about chord distribution and working with scribal mistakes. It has a very short subject, just one bar and a beat long. The 2nd entry, in the dominant, is introduced by means of a climbing Eingang and then is immediately interrupted by the third entry after two beats. So the distance between entries is 6 beats/2 beats. In many ways this is just a slightly naughty gambit enabling the composer to construct the whole fugue as a game throwing back and forth the superimposition of Crochet-Crochet over Quaver-2 semiquavers-2 Quavers, which offers opportunity for virtuoso display in two and three parts, and not so much actual fugal development. In addition, the very simple nature of the subject itself, a scale meandering around the tonic, over just a 4th, gives Nardini lots of room to play with close imitative writing and similar motion. The more vertiginous, chromatic or involved a fugue theme, the greater difficulties it will pose a single performer as it is developed. The exception to this rule is the extraordinary fugue that Antoine Reicha would later compose based on the two-octave-leaping first subject of Mozart’s Haffner Symphony.

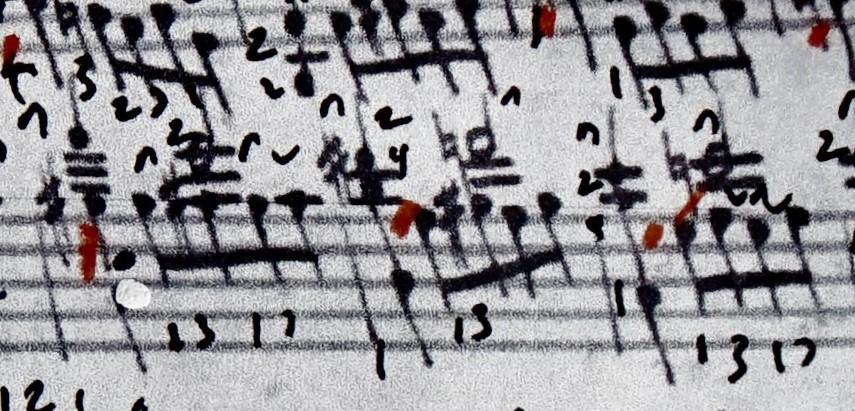

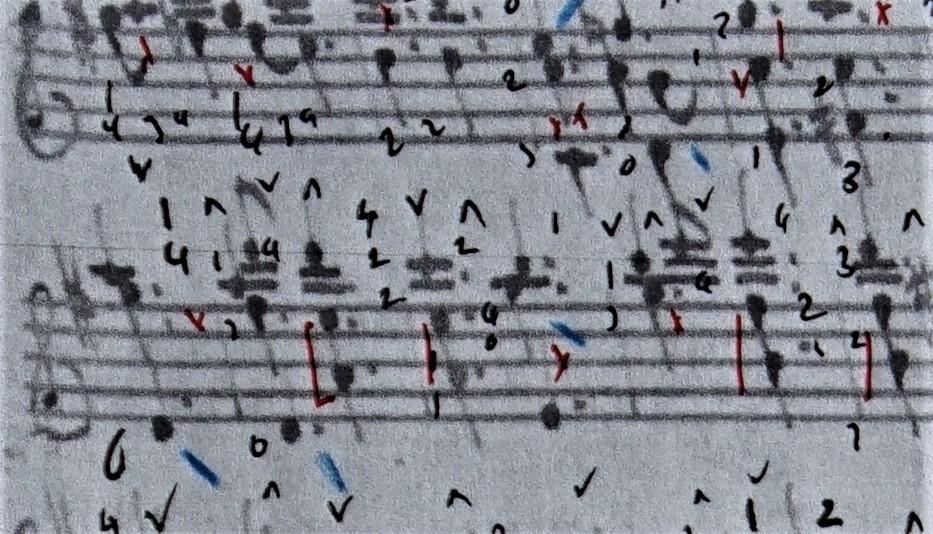

I would first of all like to talk about working with mistakes in a score.

It’s important, to be able to disentangle mistakes from unfamiliar notational conventions. As I have talked about below, our normal notion of time-space notation, based on a notional vertical line travelling from left to right along the stave, does not serve for most 18th Century manuscript. So, if we look at the two bars of music on the upper stave, we will soon realise (also by comparison with the rest of the course of the score) that the three isolated quavers on the top part are not aligned with the crochets immediately beneath them, but are off-beats. The minim in the last bar of the line below is not syncopated, but starts at the beginning of the bar-this is an instance of the ‘Christmas Tree’ convention I have discussed immediately below.

You will see that there are two kinds of fixes in the last bar of the first line of this segment. The first is the most commonly needed in 18th century writing -adjusting an accidental. In this case, the D sharp which I have added is not technically a correction, but, yet again, brings the score closer to 21st century convention. As harmony came under threat from chromaticism and enventually, notional atonality, from the mid-19th Century, it became standard practice that an accidental was required each time a pitch appeared in octave transposition within a measure. Nardini’s generation would automatically see this note as D sharp. Even though I know the convention, I need to stop and check (mainly because of the history that stands between me and this music), and then add the notional correction.

The white ink fixes two common lacunae, extra ledger lines and, in the lower line, a sequential figure, which has wandered off course (one tone flat) in the writing. It’s worth noting that the other copy that exists of these caprices, in a very neat hand, scrupulously repeats all of these mistakes. As one gets more acquainted, friendly even, with the character and notation of a composer, the gamut of common errors becomes clearer and easy to predict/fix.

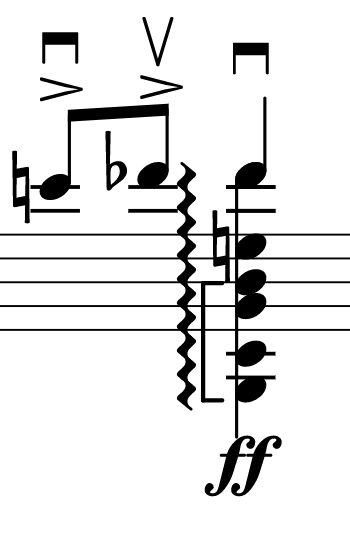

The other passage I would like to highlight raises the spectre of chord ‘spreading’. Players who hold to an exclusively ‘not listening’ modern-lots-of-vibrato-I-wish-I-was-Henryk Szeryng approach are pathologically averse to the myriad possibilities of how a chord might be spread, explored, if you like even strummed. They generally want either ‘all in one’ or ‘two-two’: whack, bang. I still remember the shock, in my early teens, when I was feeling my way through the Eugène Ysaÿe solo works, at finding 5 and 6 note chords. However, by the time Ysaÿe wrote his 6 Sonates down, in the 1920s, the understanding of how this was achieved had eroded so much, that he had to bracket the chords to show us how to negotiate them. Here’s the most famous example, from the 3me. Sonate.

You will see that the Nardini example is not that different. It’s actually hard to find an 18th century Italian violin composer who did not do this, and early, Lonati is full of it. It raises all sorts of questions, as to how to execute it. The solution I have indicated, means that the A string can be ringing, whilst I step from C sharp to E (1-3) on the E string, but now I am also experimenting with a chordal solution, player the top Csharp on the A string. The jury’s still out.

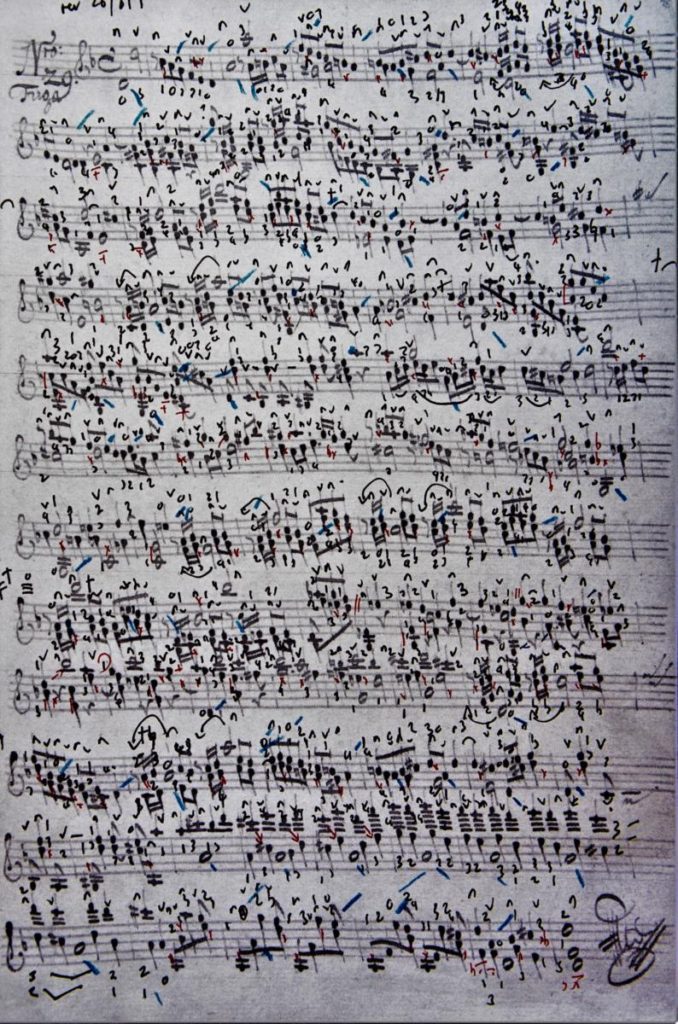

Book 2 No 29 D minor Fuga

This fugue takes the ‘what’s possible’ versus ‘what can we imagine we are hearing’ debate which I have hinted at below to a new level. It’s worth noting, that in the 19th century, this question, which is, in part, a notational one, spilt briefly, into semi-public attention thanks to the playing and composing of Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (1812 –1865), who published works, most particularly his Polyphonic Studies which include notation of chordal material which can’t be realised unless the played length of notes is not always the same as the written.

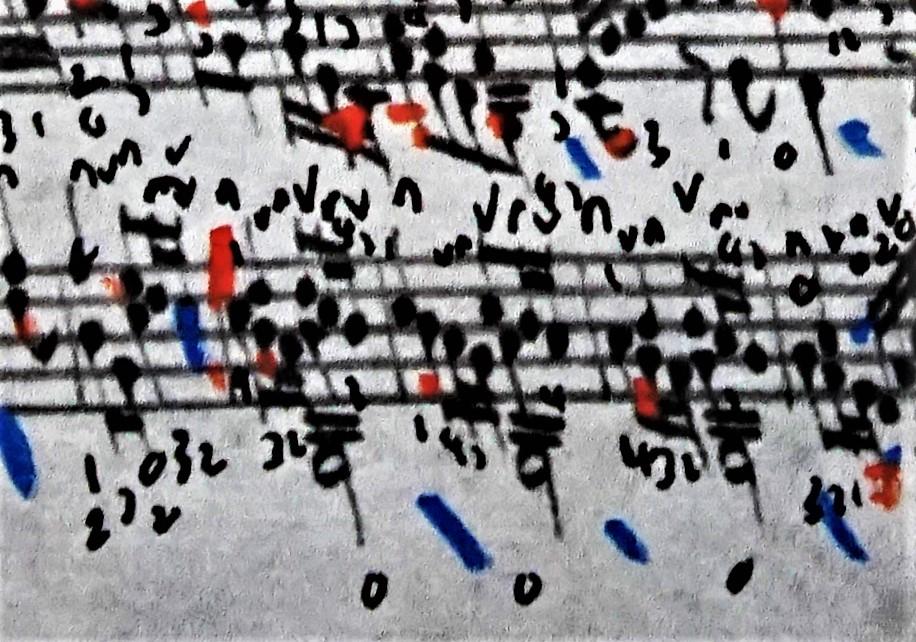

But I would like to draw attention to the flexibility, the poise, if you like, that Nardini demands of the left hand, and presumably found easy himself. Look at this marvellous passage in the coda.

Look at the section with the long pedal A. This pedal is to be played with the open string throughout.You will no that it begins canonically, and then the composer abandons the canon after three bars when he needs to bring the sequence downwards. This is quite simply a practical solution. At the beginning of bar four of the segment in question, the top line has reached the Bflat two and a half octaves above the open E. There’s simply no way of playing the material descending on the top line, whilst keeping the sequence ascending (it would have been E-G-F-A) on the low line, which is all played on D string. If you try it out, you will find that you are in the midst of a technical ‘cat’s cradle’ – in the middle of an already complex passage. Because, what is remarkable about this section is what it reveals of Nardini’s dexterity, controlling the 1/2 3/4 stepping tenths on the D and E strings, whilst avoiding brushing the open A string, is not easy. One might suppose that this is the kind of technical procedure that would have been made easier by the advent of chin-rests (and later, pads and the cursed shoulder-rest). However, it’s clear to me that not having these devices on the instrument meant that players such as Locatelli, Nardini, and Paganini ( to take three generations of Northern Italians, were able to hold the violin in a flexible way: it’s easier to get to these high chordal figures straddling open strings when the angle of the violin can be adjusted, to and from the chest, the neck and the shoulder. The proof can be found in the works written after the advent of these so-called ‘improvements’ – an lessening of the options for chordal playing across the instrument in high positions. There’s no doubting that Nardini would have found the chordal arpeggiations at the beginning of Arvo Pärt’s Fratres (violin version) lacking in technical sophistication.

But lets return to a question of notation, and the modern mindset. This sequence occurs twice in the fugue.

I have already mentioned some of the challenges, for the modern player, or working with 18th century manuscripts, even when they are as neat as this one. Have a look at the sequence above. I have scrawled in some ugly arrows, which indicate where the minims/half notes should be placed. It’s important to note that Nardini has placed them absolutely correctly, and that a player of the time, would have no problem playing them in the right place. The quickest way that I can illustrate the reason is this, the ‘Sept figures de notes’ from the Méthode pour le violon by Antonio Bartolomeo Bruni (1757 — 1821). Look at how the diminute-ing note values are arranged.

As you can see, the notes are orientated from the middle of the bar, and as they get shorter, they fill the bar up from that point, like a Christmas tree. It you look at every bar of Nardini, that is how they are organised. If you had learnt to read music like this, and not in the left-to right space-time tyranny that has been most musicians training – this is completely natural. Now look at a Beethoven MS. And there’s the same thing. So much has been lost, in abandoning this principle.

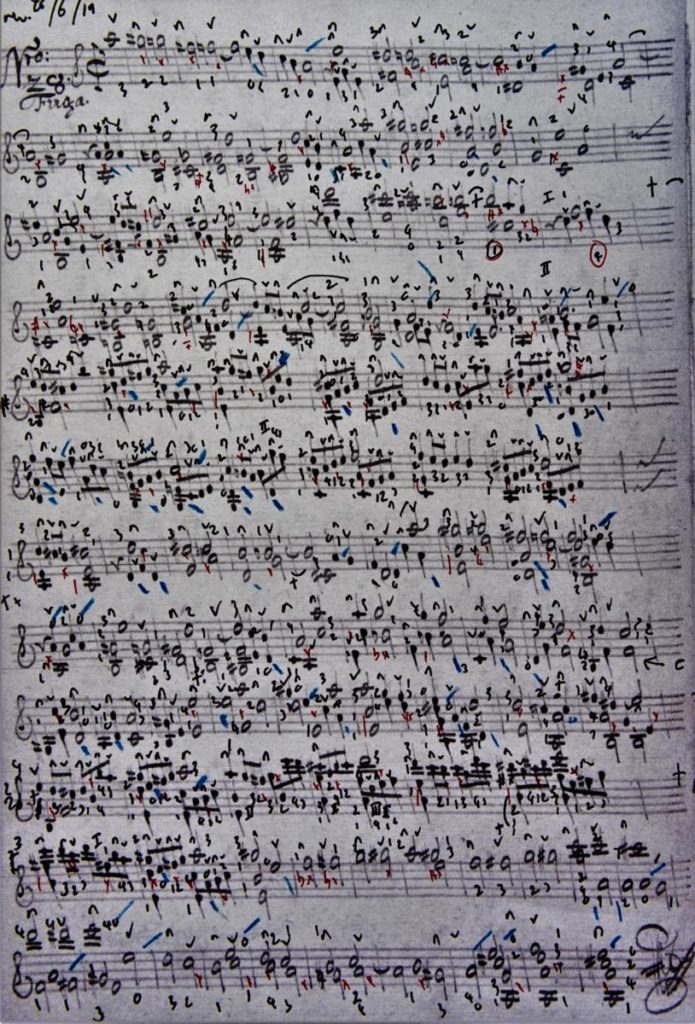

Book 1 No 28 A minor Fuga

There are twelve or thirteen fugues in Nardini’s two volumes of caprices. This makes his contribution significant. What is immediately clear from playing and studying his fugues is this is not music ‘written into a vacuum.’ My impression is that the works are written for a player (himself) for whom the contrapuntal techniques on the instrument alone were, can I say, quotidian.

I have more of an interest in fugues for violin alone than the average player. I have commissioned a number of composers to write them for me (David Matthews wrote a set of six), and am particularly interested in their manifestations in the compositions of the ‘Revolutionary Generation’ (Viotti and his disciples- the two generations that followed Nardini).

Which brings me to my first point about writing and notating fugues on the violin. Any contrapuntal essay on an instrument with this particular set of limitations and opportunities will pertain to one of three types. The writing can be ‘idealistic-through composed’ – that is, the material will have been composed without concession to the instrument, as an exercise in pure counterpoint, leaving the player to solve the problem. Or the opposite -the fugue might be written at and around the instrument: such writing will relate to what I am sure was an active tradition of improvising contrapuntal music on solo string instruments. Or, as is the case here, the writing will be a melange of these two approaches. How is this manifest? Let me clarify.

Here’s the exposition of the A minor fugue. The rhythmic structure of the 5-bar subject is notes 4 – 2 – 2- 2- 4 – 1 – 1 – 1 – 2 crochets long. Of course, when the theme is played at the beginning, solo, there’s no problem with the length or the shaping of these notes. However, when the second entry comes in, in the dominant, at bar 6, the counter subject below (Crochets, E G E) makes it challenging to play the opening note of the subject full length. Immediately, it will be clear, that in order to have integrity across the whole piece, it will be necessary to ‘poise’ the initial statement of the fugue, so that when it has to be re-shaped in order to accommodate 2, 3, and intermittently, four-part textures, it should not have travelled from a recognisable identity. It will be clear that Nardini has chosen to not adjust the note lengths of the ‘pure’ fugal material at any point in the piece for the sake of instrumental convenience. The player knows what they are aiming for, conceptually, internally, and finds a solution which aims to approach this integrated compositional approach with the minimum of compromise (and inevitably, with something of a bad conscience).

However, it will be noticed that this intellectual rigour is slackened somewhat when the piece relaxes into episodes and sequences – the bridge passages between the more, dare I say, cerebral, fugue edifices.

In this passage, it’s clear that Nardini has made, effectively, a half-way house, between the violin-istic convenience (see the crochet-length three-note chords punctuating the running quavers)and the minimum-crochet notes which recall the syncopation across the 3-4th bar of the fugue subject.

I would argue that the second example, is writing ‘from’ the violin. The first is rooted in the all-important notion of fugue, of counterpoint, as the most refined music-making, the music of thought. The irony, and this is manifest here as in Bach’s three fugues for violin alone, is that the effort necessary to bring these two approaches into the same space, in performance, and the very impossibility of honestly realising some contrapuntal gestures can result in exciting virtuosity – but virtuosity in the true sense, aimed at, what, forgive me, is a noble end, rather than showmanship.

Book 2 No 1 C minor

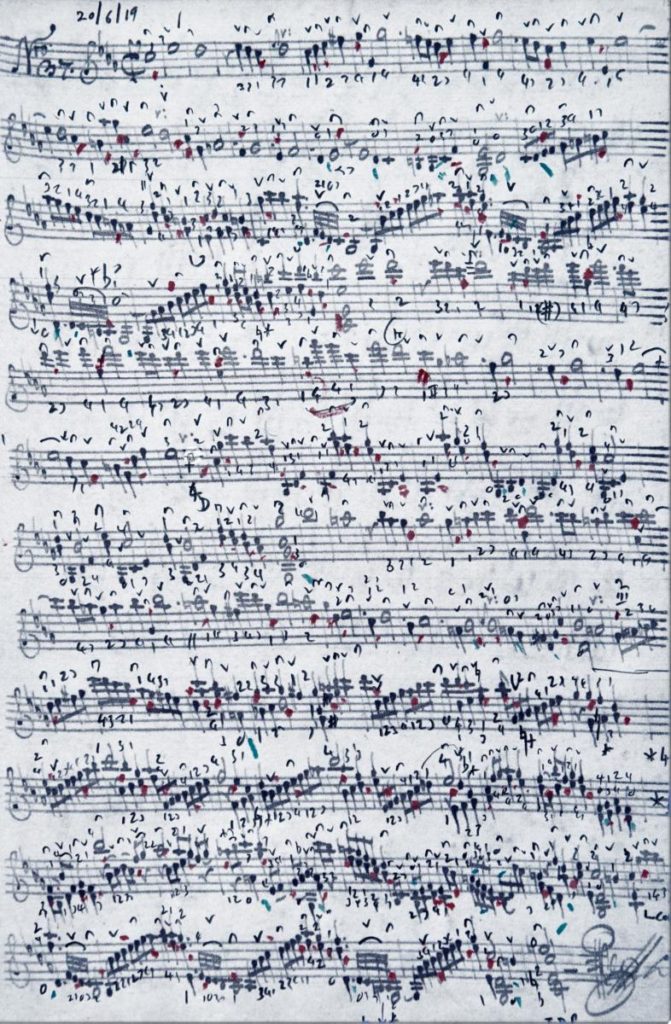

This caprice has something of the feel of a prelude, which is unsurprising, as Nardini clearly felt that he wanted to mark out the opening of the second volume of pieces. It’s worth remembering that the Paganini 24 Capricci were conceived and originally published, in three groups of 8 (Opii 1-2-3). It’s a trite observation, perhaps, but there is a relationship between the character and function of this caprice, and the decorative calligraphy of ‘Capricio 1’. which gives me a perfect excuse to talk about the ‘composer’s hand.’

Spending time with a manuscript gives me the opportunity to become comfortable with a writer’s handwriting. I have lost count, of the number of times,that I have realised, after a number of days with a score or handwritten text, that the author’s way of expressing themselves on the page, seemingly so obscure at the outset, has become second nature, that I am reading, rather than decoding. This can begin with something simple – not, being stumped by the way a composer writes their letters. It took me, I confess, a few iterations, to get comfortable with Nardini’s ‘C-shaped’ letter P – look at the word ‘Presto’ in the example above, which I no longer read as ‘Cresto’. By the same token, one has to get comfortable with a writer’s abbreviations: Nardini writes ‘Ada:’ or ‘Adag’, for ‘Adagio’. These are little things, but only one step from the more complex issues of musical script.

The first and last lines of this caprice offer a simple window, into the the crossover between improvisation and composition. The opening gesture occurs three times in the piece, but on its last appearance, it is decorated – the three quavers which end each bar have been ‘broken’ into ascending arpeggios. This is a standard method of making ‘divisions’ or filling out a chord progression (think of Bach’s Prelude No 1 from the 48). When you look across this 110 pieces, you will find that most of the musical material has been developed, evolved, using these processes: this is the work of a composer who is, primarily, an improviser.

Book 2 No 2 A Major

A question of stretching, and perhaps, more conversation with Locatelli. I confess, that this was one of the caprices that scared me, until I spent time with it. Its in an ABA form – the outer sections initiated by a brilliant series of bowed-out ‘turns’ and with some Vitali-like leaping bowings. But it’s the middle section, a series of arpeggiated chordal ‘flights’, which initially frightened and now fascinate me. I would like to write a little about hand position, stretching and contraction. Here’s an joint-popping example, played with the low E on the G String, and the high B on the E, to get you thinking.

Curious to relate, but as the violin became more fixed by devices such as chin-rests and (ugh) shoulder-rests in the 19th and 20th Centuries, the range of stretches and contortions demanded by composers ebbed somewhat. There’s a simple, but almost-never-stated reason for this, which is the increasing immobility of the instrument (climaxing in a number of nameless contemporary virtuosi who seem to have affixed the instrument under then neck with IKEA shelf-brackets). If you are not able to adjust the hold of the violin, all of its angles and proximity to the neck, the rib-cage, the upper arm, then many of the extreme hand-openings demanded by 18th century virtuoso music will be out of reach. Here’s a photo of the widest stretch in the example above.

1st finger E on the G string, 3rd finger muting the D String, 2nd finger, C sharp on the A String, 4th finger B on the E string.

Drawing the violin low (think Mischa Elman in later years) enables the had hand to fan out and not reach the extremes but for the 2nd finger to play the middle line sequence, 7ths below the top note. This is much easier to approach if you work on it without the locking effect of a chin rest. The Nardini set is full of such examples. So I will be talking about it a lot more as we find our way through the whole set.

There’s an interesting challenge in bar 5 of line 6.

Remember that this is shorthand notation for a semiquaver bariolage to the open E String – as series of fingered thirds from bar 3 (against the open) until – Look at the second minim or bar 5,the hand has to leap down, extend, and incorporate the passing low D sharp, into the pattern, before floating back to the thirds in the next bar. This is the kind of commonplace suppleness that Nardini demands.

Book 2 No 9 G minor (23rd June 2019)

Slurs are conspicuous by their absence through much of the cycle. Nardini was celebrated for his legato playing, so one can be sure that this is not an indication that they should be eschewed completely. However, in s study such as this, any player has to make a decision, which they may come to change or even regret, based on the material in front of them, and the stylistic ‘portrait’ which they might be beginning to assemble of the player-composer and/or the aesthetic world of the piece/pieces in question. In the case of this stormy G minor caprice, I made the decision to add slurs in two areas, and was tempted by a third.

Here’s the first example, a double stopped figure of four quavers with a triplet semiquaver counterpoint, which appears 15 times in the piece. I decided to slur the sixteenth notes in order to allow the eighths to ring. Please don’t infer from this, that I play the figure with a legato stroke. It is still slighlty ‘lifted’.

The second instance, in which I chose to add slurs occurs just once, during a cadenza passage on line 9 running up to the coda. It seems to me, that the figure would be served best by a ‘pleading’ bowing, grouped in twos, which has a human, emotion filled quality which suits the drama at this moment. It’s an outlier – this figure has no partner anywhere in the caprice, which is a good argument for using a bowing technique just once.

Finally, here’s a spot where I decided to not slur -an outbursts of demi-semiquavers on the second line. Not slurring, means that this passage has a brilliance – however, I can imagine, that mid performance, I will change my mind!

Book 1 No 47 A Major (22nd June 2019)

If I was to give an example of a technical aspect of Nardini’s writing which sets him aside from his master, Tartini, then it would have to be what I have to call, the left hand ‘lock’. Almost without exception, Tartini’s virtuoso writing constantly ‘refers back’ to the nut of the finger board, to the low positions. This is particularly the case when he is writing for violin alone, where he is careful to keep the violin ringing as openly as possible. Nardini, by contrast, looks forward to the technical expectations of Paganini, and in the early 20th Century, to just name one example of many, Leoš Janá?ek (particularly in the two string quartets), who used what guitarists would call ‘barre’ technique, where the set of the hand across the fingerboard is used as a foundation more and more intricate reaches, far away from the comfort of the low positions, and the open strings. Nardini combines this with contracted and extended hand positions, most particularly in sequences. Here’s an example from this caprice:

This innocent looking patch of three bars contains an example of how Nardini was pushing technique towards the sophistication of Ernst and Paganini in the next century. As well as the opening and closing of the hand, this also exhibits a crucial ‘no chinrest’ shifting technique, where the hand shifts up or down by an internal contraction between the 4th and 1st fingers, and opening, up or down from the low or high side of the ‘bunched’ position to move along the fingerboard without being driven by the arm, and avoiding destabilising the instrument.

I would argue, that Spohr and Bull’s innovation of the chinrest, which certainly enabled certain new flexibility around the violin (particularly with rapid downward shifting), also resulted in a cruder, approach to left arm movements, analogous to a move from lace making to baseball pitching. There was a gain in terms of excitement, energy, and maybe even colour, for sure, but something was lost along the way. These caprices offer a window into some of these technical felicities.

Book 1 No 31 C major (21st June 2019)

In my previous posting, below, I started to talk about key colour. Well, actually, I got distracted, from talking about the essential darkness of C minor and was waylaid by Bach. So I will try again-if you like, at the beginning as this caprice is in C Major. This is key is so fundamental to us, that sometimes I forget to think about what its choice might mean. In his Ideen zu einer Aesthetik der Tonkunst (1806), Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart (1739 – 1791) wrote: C Major Completely Pure. Its character is: innocence, simplicity, naivete, children’s talk.

‘C Major Completely Pure. Its character is: innocence, simplicity, naivete, children’s talk. ‘

I think that is a useful place to start with this piece,which is somewhere between a minuet and a gigue, and full of playful figures. A gambolling, leaping repeated sequence occurs at several moments in the piece; children turning cartwheels, or doing hopscotch, if you like.

As will be seen from my markings on this section – there’s an immediately question here. It you are playing in 3/8, which already poses significant bowing questions for a binary instrument like the violin (UP/DOWN), how do you get to the down-bow on each bar line? The solution which I offer, would be exhausting with a Tourte-model bow (unless executed low in the bow and ‘in the hand’. But with the Tartini-type bow which we are sure that Nardini used, it seems to be ideal. Let me explain why-imagine this passage as imitation, of an instrumental ensemble, of say Bassoon and two oboes. I will come back to that. If I use the bowing which a ‘conventional’ modern instrument player might pick, I might play DownUpUp. There’s an problem integral to this, which is that in the change from up to down bow, even with the string crossing, the Down-bow note will be slightly deadened, as the bow leaves it to change string and direction. Playing DownDownUp, with the anticlockwise (to use Szigeti’s apellation) means that as the bow leaves the lower string and traces the arc of the retake, which it needs must to get to the second down-bow, it not only leaves the lower string ringing free, but, as Yo-Yo Ma would observe, puts ‘top-spin’ on the note: the slight increase in bow speed which is generated as the bow prepares for lift off, adds to the ‘insitia’, the innate force, of the note, and it gathers intensity as the bow leaves the string. This brings me back to my little wind trio.

Naturally, our bassoon plays a firm down beat on the beginning of each bar: > – – > – – etcetera. But if you think of our two hotboys, playing on the 2 & 3 of each bar, they will naturally stress the first of their notes thus > – . So the combination of Bassoon and Two Oboes will look/sound, something like this > (>-) > (>-) > (>-) > (>-) . This is far closer to Downddownup, than Downupup.

Book 2 No 37 C minor (20th June 2019)

As you might have read in my earlier posts, the question of counterpoint, of fugue, looms large throughout this set of caprices. I hesitate before writing this, but this caprice can/might/could be described as a ‘one voice’ fugue. And by that I don’t mean the trickery which Benjamin Britten essayed in his Frank Bridge Variations, where the subjects and answers are all built into one unison line. This is far more allusive, but to my ears/hands, the only way to hear, feel, play this work, is to as a fugue, but one which eschews counterpoint or even chordal writing int he expositional or development material.

Here’s the opening. Play, read, or sing it, and ( I think/hope) you will see what I mean. If you treat it as a six bar fugue, with three entries -the second and third silent (canonic), then you might hear what I am driving at.

The composer who comes most to mind here, is Teleman: in his 12 Fantasies for violin and 12 for Flute, one finds a number of movements which can either be viewed as ‘failed fugues’ or ‘sleight of hand fugues’. LINK Its very likely that Nardini knew, or had played Telemann’s solo music, which was extremely popular (Leopold Mozart even passed off some of the duos as his own.)

The composer who comes most to mind here, is Teleman: in his 12 Fantasies for violin and 12 for Flute, one finds a number of movements which can either be viewed as ‘failed fugues’ or ‘sleight of hand fugues’. LINK Its very likely that Nardini knew, or had played Telemann’s solo music, which was extremely popular (Leopold Mozart even passed off some of the duos as his own.)

There’s no question, that one reason that this caprice is so suggestive of some contrapuntal game is the key. Immediately upon hearing the opening three whole notes ‘C-Eflat-D’, laid out in this manner, my first thought is of Bach, most particularly, the Ricercar a 3 from Bach’s Musikalisches Opfer, BWV 1079. I think that it’s the tessitura, and the ‘alla breve’, though, of course, Nardini’s is notated with the thematic material on the barline not dividing then measures in half.

I think that it is clear, that Nardini wants to elicit a ‘fugal’ response. When I showed this to Daniel-Ben Pienaar, one of the great living Bach players, his response was:

‘I start imagining the second and third voices … are you sure that there isn’t something missing. ‘

Conversation with PSS 21 6 19)

Perhaps I should treat this as a ‘Ricercar a 1’. Here’s the ‘contrapuntal material’ laid out graphically in two ways – the red with the rising gamut from C sequentially from left to right – the blue laid out left to right in order of occurring, with looping back for the reused notes. I find it useful.

The biggest challenge of the whole set of caprices, is the number of errors, with which the score is littered, by modern standards. However these make a lot more sense, if you choose to regard the MS as a mnemonic for the performing composer, if you like, a knotted handkerchief for music. This caprice is comparatively free of error, but there are about 20 mistakes, or areas of doubt. A few of these are clear wrong notes, but more result from an inevitable ambiguity from writing sequences including rising scales in the minor, when exploring the grey areas between harmonic, melodic descending, and ascending. There are 12 ascending eight-note scales in sequential passages in the piece, and, as one works through the sequences, it becomes clearer that Nardini has (maybe) not completely made up his mind as to whether these should be ‘real’ or ‘tonal’. Perhaps, seen from the point of the improvising musician, which he was, it’s a moot point. You just have to make your mind up to stick to a decision.

One last observation; on rhythm and syncopation. 18th century solo violin music is not very creative rhythmically. We need to go back to the Sonatas of Westhoff, or the work of Matteis the Elder, to find rhythmic displacement or syncopation. However, this work relies on an unheard sense of pulse, of measure to explore off-beat possibilities in the ‘fugal’ sections. One might argue that this is a deliberately ‘archaic’ gesture, a wave to the masters of the previous century, particularly, in northern italy to the work of Colombi and GB Vitali (whose Diverse Sonate e Partite are full of this kind of thing).

Book 2 No 25 G Major (18th June 2019)

Coming back to the cycle tonight, I found that I am fascinated with the question of arpeggiation explored below. So forgive me if I stick with this type of material, its notation and execution.

The prosaic stuff first: this caprice is written in the type of simple shorthand seen in Bk1/24. The pattern is inverted-with the strong beats on the top string , I-III-IV-II-III-IV- I-III-IV-II-III-IV, makes up the shape of most of the bars. As will be clear, this demands the kind of skipping over strings which I discussed yesterday. Just to note, this kind of precise sequencing became increasingly rare from the end of the 18th Century onwards. If you take a look at the arpeggiated Paganini caprices (1, 2, 5, 11, 15, 20 arerelevant) you will see, that whilst he uses a lot of energetic leaps across multiple strings, there’s none of the delicate control that this style of figuration/arpeggiation demanded here, and throughout these pieces.

But lets talk about fifths. An ongoing ‘querelle’ in 18th century violin playing regards the position of the hand on the low strings. This caprice makes it crystal clear, that Nardini demands that the player has enormous control over tightly held and contracted chordal positions (such as the C sharp-A – E- G 2331 in bars 3 to 4 of this example) and is prepared to cover and hold a perfect fifth as the foundation of a chord, with the 4th finger (something which occurs comparatively rarely in Bach -where it is clear that, in 90% of cases, he has allowed himself the cheat-option of a spread or open strings). Bars 1,2, 5 and 6 of the example given can only be played 4421 (the voice leading from bar 4 to 5 makes that crystal clear). This requires a particular setting of the hand, and, remember, needs to be approached in a NO CHIN REST mindset. The preservation of the boring figuration established in bar 1 makes it clear, that no cheating is permissible here. It takes a little while, and I recommend a couple of hours in the middle of the night with the instrument and a cup of tea. But once you’ve learnt it, if you are me, you will be wondering why it’s not part of your usual box of solutions.

Book 1 No 24 C Major (17th June 2019)

All but three lines of this piece are written in the standard 18th century shorthand for arpeggiated material. The first bar offers the model for the shape of the figuration and from then on the material is late out chordally and rhythmically – meaning that all that is shown is the movements of the left hand to which the bowing pattern is applied. There are some 18th century notation conventions which this flags up, which are unfamiliar to a lot of musicians today. Here’s a close up of the first three bars of line 8:

The first convention is the relationship between note placement and length. Until the middle of the 19th Century, this was seen like a Christmas tree within the bar. If a note is the full length of the bar (see the dotted minims) it is placed in the centre of the measure. As the values are halved, the notes are placed symmetrically from the middle of the space-resulting in the offset which can be seen above. Nardini adds a couple more conventions. The first, visible in the second bar of the example I have offered, is that when the bar filling material makes a dissonance, the notes are offset. Nardini, as you can also see here, extends the notation shorthand: the low voice in bars 2-3 is the same as bar 1. But lets talk about bowing:

As you can see, bar one gives the four string bowing pattern. Bar two onwards makes it clear that this is four string and not three – so the pattern is IV-II-I-II-II-I-IV-II-I-II-II-I throughout. This necessitates the string hopping approach to bowing which I have discussed below, and which I am beginning to understand, is key to Nardini’s approach, whilst being almost entirely absent from his master, Tartini’s. I see this as what ‘spring-bowing’. Playing this with a Tartini-model bow, which has not natural ‘bounce’ it is clear that this, and related patterns, have to be executed by the active control of the bowing hand in the air, akin to choreography, or fencing moves. This theme will develop in later posts.

Book 1 No 46 G Major (16th June 2019)

A number of this cycle of caprices are contrapuntal, or even, as in this case, fugal. This etude is a two part fugue, which has more than a few similarities to the astonishing two part fugue at the heart of Viotti’s Suonata (Listen here) There’s an all too prevalent notion, that between the three fugues of Bach’s Sonatas & Partitas and the contrapuntal works of the 20th century, interest in contrapuntal writing for solo violin declined int some way. We know that, at the beginning of his career, Paganini composed a set of fugues (it is not known for what instrumentation). As will be clear from my comments below, Paganini himself was, somehow , aware of elements of Nardini’s contrapuntal writing. The reason for the misunderstanding noted above is simple: there has been a wilful neglect of the solo music of the mid-to late 18th century. This is not because it was not published in later editions. Indeed, anyone who has studied Ferdinand David’s Violinschule (1863), will find a number of examples of the solo works of this period, treated as canonic works to be studied.

This caprice is a pure two – part work. Nardini only allows himself three and four part chords at structurally important moments – anchoring the relative minor, the dominant, and during the stormy sequence begins the fugal development before the move back the tonic. Despite all this, the caprice, presents an aesthetic choice, or challenge to the player, regarding what, today, we might call ‘verticality’. Throughout the cycle, as I have noted below, there are a number of chordal passages that demand that the bow ‘skips’ over an intermediary string. This is not something which makes sense with a ‘modern’ Tourte-model bow, but with a mid 18th Century Italian model ( I am using an Airenti copy of the ‘Tartini’ bows kept in Trieste), the skipping technique is second nature. This gives a clue as to how a number of points in this caprice should be played – bar 1 of line 9, and bars 2-4 of line 10. At both these points, we find tenths notated. My instinct, and this might change, as I spend more time with the set, is that these should not be played with the virtuoso ‘vertical’ 1-4 fingering, but should be played with a ‘skipping’ fingering and bowing. This produces the kind of voice leading which is familiar from harpsichord practice for music of this period. It seems right to me, though I may come to change my mind!

Note the economical notation of the tied crochet from bar 2 to 3 – the dot extending the minim D is simply placed on the right hand side of the bar line. This lovely convention avoids introducing the idea of a mesa da voce that can seem right when the three beats are notated with a tie to a crochet, and replaces the inappropriate sense of syncopation with a charming hemiola 3/2, 3/2, 2/2 across the fugue subject.

A rare device in solo violin writing appears in bars 2-3 of the last line of the caprice, a descending sequence of suspensions and releases octave-ninth-octave-ninth … . This seems to be the perfect place for a somewhat ululating 1-4 fingering, full of ‘portes des voix’.

Book 1 No 44 C Major ( 16th June 2019)

I spent this afternoon untangling some of the issues around this caprice. At this point, I think that I can confidently say, that (if this is Nardini’s hand) this ms has been copied out somewhat carelessly. This may simply be inevitable by-product of the unenviable scribal task of copying our 110 pages of dense solo violin music. Or, it might be the more commonplace result of a composer writing out a score ‘neatly’ and, consciously or not, treating it as a mnemonic, a memo to self, or not being able to see their own mistakes.

So a few performance notes. 6 lines down, we see a sequence in standard notation for arpeggiation. Some composers offer exemplars at the start of a divided chordal passage of this type. But, to be honest, this is one of the simpler examples in this sequence of pieces, and simply sets a paradigm for notation. The context of the surrounding bars leads me to suggest/suspect, that it should begin/end in a manner which leads to and from the 16-note figures logically (that might mean playing 16th note spread chords, or one might chose to arch from and to these note values).

It’s interesting, that the score only offers one cue note for a subsequent stave. If look at the end of line 2, you will see the indication that the lower part on the next line begins with an F sharp. This seems to be Nardini’s practise – if you scroll down to Caprice 50, you see the same convention at work.

Now for some more complex notation:

One of the big questions in writing contrapuntal music for a bowed instrument like the violin, with an arched bridge, is the relationship between sustaining notes and suggesting that they should be sustained. This pedal sequence, which occurs twice in the caprice, offers an interesting model. There are three parts-the low G pedal and and two imitative treble parts, marking out a simple descending sequence. In order to have a real clue as to how this might be executed, I think, it’s necessary to play with no chin-rest, which demands that downward shifts need to be done with economy and directness (to avoid constantly drawing the violin away from neck). It’s pretty obvious to me that this passage, and its sibling, earlier in the movement (line 3), should be ‘solved’ with a shift on each bar line (what Leopold Auer called-‘rhythmic shifting’). This has the result that that last note of each bar in the upper line, strays onto the string of the middle line. Any sustaining of the lines, must perforce be purely acoustic, or in the memory (in the mind’s ear, if you like). This sets a fascinating model for the rest of the cycle.

Book 1 No 38 (12-13th June 2019)

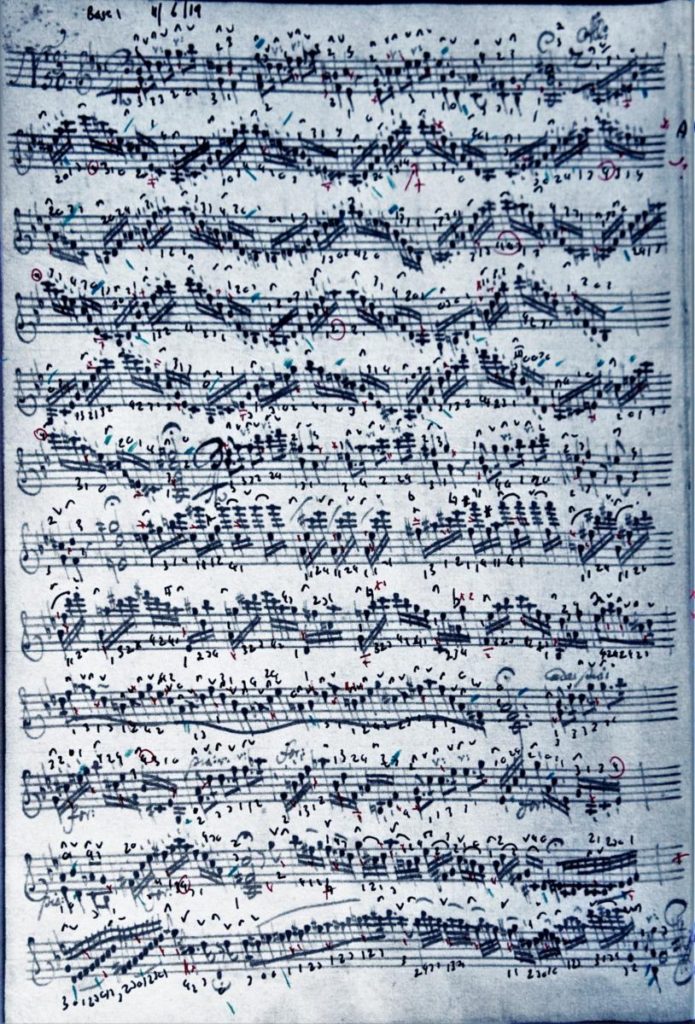

So, I confess that I got tripped up, working on this Capriccio over night. It raises all sorts of questions and ideas about how our musical language is shared, remember and passed on. I will explain. Here’s the full text, with the first stage of technical annotations, with errata noted along the margins.

I confess, that I chose to work on this G Major caprice last night because it is less challenging (technically, and textually) than some of the others. I had spent the whole day stuck in the editing suite, and was not really prepared for a hard night’s technical slog! As I have described in some of my writing on practice I don’t often begin for on a piece at the beginning, or with primary thematic material but with something apparently insignificant. So spent 40 minutes or so teasing out the notation of some of the bridging material, before turning my attention to the opening.

It was very familiar. Take it up a tone, and you have this. LISTEN

This is a short prelude for solo violin, which Paganini inscribed in an album in 1838, two years before his death. It is the same material as the thematic core of Nardini’s piece, albeit up a tone. It’s worth noting, that Nardini’s collection of studies is not, shall we say, entirely his own. There’s at lease work which is purloined from Locatelli. The muscial gesture which Nardini and Paganini have both used, is, yes, sui generis. But the hand positions, particulary in triple-stopping, are not. Which leads me to the tentative conclusion, that Paganini had had contact with this work, most likely when he was studying. I suspect, that the pieces stayed with him (and the contracted chordal hand positions are exactly the kind of thing which are to be found, for instance, in his 11th Capriccio. Perhaps he used the sequence, over the years as a basis for improvisation, or a warm up (I have one from the cadenza of the Nielsen concerto which drives my colleagues mad in the dressing room). Whatever the case, it clearly sprung to mind when he was presented with the album. It’s worth noting that, bu 1838, he had, to all intents and purposes, been forced to lay the violin to one side.

One thing to note, is that Nardini clearly enjoyed the ambiguity betweeh 6/8 and 3/4. If you look on lines 1, 8 (there are more), you can see double-stopped passages, where the top line is in ‘simple’ time and the bottom in ‘compound’.

And a technical note. It’s very clear that a fundamental element of this set of pieces, is non-adjacent chordal writing ; that is, when a chord can only played by either a large internal leap, or as in this case (a it is clear that we are in what some violinists call 4th Position), a skipping execution, playing a spread chord on the G, A and strings, without touching the D string.

There will be lots more technical detail to follow.

Book 1 No 50 G minor Adagio-Allegro (11th June 2019)

When I start working on a large cycle of pieces, I don’t have a way of choosing what order to work. There’s no logic to this, but, a little like searching for the right pebble on the beach, I cast up and down, putting my hands on certain gestures, until an ‘in’ appears. If I am looking for a way to begin working on the music and technical approach of a ‘new’ composer, and that is the case with this cycle, I will either look for salient features, or the familiar.

This Capriccio looked comfortable, so I set to. Structurally, it’s interesting. ‘Adagio-Allegro’ x 2 dominates, but breaks up into a fascinating syncopated flourish, leading into a coda/cadenza where the adagio/allegro material alternates, cut up, in bar long gestures.

Note to self: this is clearly the composer’s MS, intended for themselves. There are a number of shortcuts in the notation of accidentals, and a fascinating enharmonic error on the last line: a scale of D Dsharp E flat E natural (and so on).

Under the left hand, some simple observations. This is an ‘open’ hand violinist (unlike his friend and teacher Tartini). The major tenth ‘locks’ also require flexibility within the lock of placing the 2nd/3rd finger (decide) a major or minor third above the root.

The right hand shows signs of moving towards the combination bowings that would be so loved in Paris at the end of the century. But the bowing is in a slight shorthand-bespeaking a composer’s copy. Stay open to the ‘rules’ as they appear through increasing familiarity.

Posted on June 12th, 2019 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved