So, late last night, after a delightful evening of conversation, food, wine and laughter with friends, I found myself at at the practice desk thinking about Abel and Gainsborough. I thought about Abel’s grave in the strange space of St Pancras grave yard, about his gamba, allegedly under the railway tracks, and Gainsborough’s sorrow at his death. And then at about 3 this morning, very quietly, so as not to wake anybody, I played the Adagio from his G Major Gamba Sonata. There are lots of clicks and pops, as this was a very ad hoc session, as close as possible to the mic on the desk.

Karl Friedrich Abel-Adagio from the G Major Gamba Sonata WKO155 (for Lady Pembroke)

Peter Sheppard Skaerved-Viola (Matthew Hardie/ex. Richard Meares)

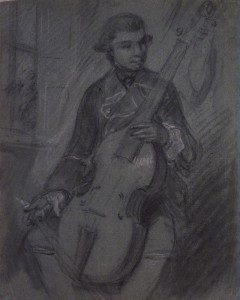

Karl Friedrich Abel by Thomas Gainsborough, (NPG 5081)black and white chalk with stump on blue paper, circa 1765

NPG 5081

Karl Friedrich Abel –

Gainsborough recorded a number of intimate drawing room performances-players and singers gathered around a harpsichord, in red chalk, and this exquisite, living, sketch.

When a string player plays, however slowly, both hands move so rapidly, the configuration of the arms is in constant flux. So any such drawing is records a passage of time-of course, this is the case with any depiction of human activity even the shortest shutter exposure. But in the case of an evening of music and discussion, which perhaps this records, the act of drawing, Gainsborough with his roll of paper, drawing, was perhaps part of the activity. Perhaps they discussed the drawings as they appeared-maybe Abel criticised the artist’s depiction of the hands on the instrument (a notorious subject) which very few manage to conquer.

The great Haydn authority, H C Robbins Landon, explained how Haydn inherited a mantle of London concert giving prepared for him by the Bach-Abel concerts:

‘For nearly 20 years J C Bach and Abel had dominated instrumental music in London, mainly through the annual series of subscription concerts, held between late January and April, in which their own symphonies formed the chief attraction. Bach died on 1st April 1782, Abel 5 years later in 1787, and there were no clear local successors … When in 1790, after repeated attempts to entice him and countless rumours of his expected arrival in London, Haydn was finally able to accept the invitation of Salomon, he was about to take on the role created by Bach and Abel, that of a composer in residence, appearing in person at each of the subscription concerts.

Thomas Gainsborough’s farewell to Abel is extraordinarily touching. Perhaps it gives voice to something that we all know, that every conversation is the last time that it will be had, as well as the first, that every phrase is the last time that will be shaped like that, that every line in charcoal on a page, is unique, and a reminder that all fleshe is grase. The note dies as soon as it is given life-that is its allure. Elisabeth Vigée-le Brun’s farewell to her musician, Giovanni Battista Viotti is oddly similar:

“My God, how I wish you could be with me so that I could listen to him speak, with so much expression on his face, and the sweet sounds which I so loved hearing. Why do I not hear them anymore! They are still in my heart, and I continually say to myself Encore, Encore”.

There is certain condescension, in our sense of the word, in the modern attitude to the great amateurs. I am not entirely sure why this writer feels the need to point this out about Gainsborough’s gamba playing. Up till the very end of the 18th century, ‘public’ performance, that is, concerts as we would understand them, was still uncommon, and in comparison to the amount of playing that was going on in a variety of private circumstances, totally insignificant. At no time in his various musical travelogues, did Charles Burney mention it at all, whereas numerous private performances are documented-these invariably involve amateurs as collaborators. What is there that prevents us from seeing that a great artist like Gainsborough, or a great intellect like George Bernard Shaw might bring something unique, even transcendental, to their music making, however technically deficient, which was of use, or inspiring to their virtuosi friends. Once we accept that, then Shaw and Cohen playing duos, or Gainsborough, improvising with J C Bach and Abel, become something fascinating, as words are supplanted by musical exchange. We, perhaps, are mortally hobbled by an obsession with our ‘hierarchy of talent’.

The chamber music enthusiast Walter Willson Cobbett was adamant that the meaning of ‘amateur’ should not become occluded. In his Cyclopedic Survey of Chamber Music, he remarked:

“For centuries, the world’s farceurs have indulged in satiric comments at the expense of the amateur in art, especially in music. They have been pleased to coin the most illogical adjective in the English language-‘amateurish’. The result is that the intrinsic meaning of a word of noble derivation has been obscured.’

The most famous amateur violinist amongst painters remains of course, Ingres; to this day to ‘jouer à Ingres’ is widely used to express the pitfalls of keen amateurism- Violin of Ingres was famously evoked by the surrealist Man Ray. Niccolo Paganini visited him in Rome in 1818, was living in his studio on the Via Gregoriana.

Ingres’s extraordinary portrait of Paganini was curiously prefigured in 1818 by a painting by his friend in Rome, Jean Alaux, entitled The Atelier of Ingres in Rome. Alaux painted him with his wife Madeleine, in their apartment, looking to the studio. This painting does not show the painter at his easel, but greeting his wife, seated, violin and bow in his hands.

Madeleine comes bustling into apartment, flushed perhaps, from running up the stairs, eager to see her husband, putting her bonnet down on the table by her portrait. What will her husband have painted today? But he is not at his easel or desk, but sitting in the studio at the side table pushed against the north wall. He has his overcoat on. Ingres seems lost in thought, as if a spirit had lately left. In my imagination, “I can’t make up my mind how to paint him…the man … the violinist …. He was here-he sat there.”

Haydn, His Life and Music, HC Robbins Landon and David Wyn Jones, Tha mes and Hudson, 1988, P.253

Viotti and the Chinnerys – A relationship charted through letters, Denise Yim, Ashgate, London, P.141 – But M Chinnery 21st November 1808, P. 202

[Cobbett P 11]

(1818 Musée Ingres, Montauban).

Ilaria Ciseris, Romanticism the birth of a new sensitivity, New York: Barnes and Noble, 2004) P. 142.

Posted on April 9th, 2016 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved