Channel Firing: For Dover Museum: WWI DMAG Joined Up Arts and Museums

Peter Sheppard Skaerved-Violinist, Artist, Walker, Writer

An Online Exhibit for Dover Museum

This post gathers the played, drawn/painted, collected and written outcomes of my contribution to ‘WWI – DMAG Joined up’. All the materials assembled here result from the project of walking, performing, drawing, collecting, reading and discussion which ran from Summer 2014-Spring 2016. Again again, we walked the ancient paths and roads from Winchester to Dover, around the coast, along the rivers and shorelines ancient and modern.

The work began in the Dover Museum inspired by the objects, ideas, stories and textures of the Exhibition which the Museum presented to mark 1914-2014

Peter Sheppard Skaerved’s notebooks, drawings and maps laid out at a workshop for students at Dover Museum. Summer 2015

A word of explanation. I am a violinist, and spend my time moving between the music of the past and present, hunting for the dialogues between our time and our forbears’. My project for Dover Museum takes World War One as a model and investigates how its narratives find resonance in our past and present. This project uses music from before, during, and after 1914-1919, imagery past and present and writing. The natural history to which Dover gives focus is a very present counterpoint to this process.

The initial inspiration for this project came from the exhibition which was shown at Dover Museum in the Summer of 2014. The textures, colours, details and emotions of that display sent me in many directions. I am grateful to Jon Iveson at the Museum, and to the students and staff of Astor College, who gave freely of their time to help me direct my ideas.

Re-imagining the path; strange pilgrimage. In 1919, the Michelin Tyre Company published their MICHELIN ILLUSTRATED GUIDES TO THE BATTLEFIELDS., for the new pilgrims, from all sides, who flocked to the Western Front, looking for answers.

But central to everything was a unifying factor between war and peace, embodied in Dover, which was the question of travel. I realised that I needed to travel, to and from Dover, on foot, in many different ways, in order to get a better feeling for the arrivals and departures, which have been Dover’s history as long as there has been a settlement there.

The essential dichotomy between the times of war and peace, I realised throws these journeys-landings and departures into sharp relief.

Barbed wire became part of everyday life, an essential tool for farmers after the war. Walkling the North Downs way again and again, I was struck, even disturbed at the sight of fresh wire, nailed onto fence posts, gleaming viciously in the morning light, or here, obscene on moss covered beech trees between Farnham and Guildford.

Barbed wire became part of everyday life, an essential tool for farmers after the war. Walkling the North Downs way again and again, I was struck, even disturbed at the sight of fresh wire, nailed onto fence posts, gleaming viciously in the morning light, or here, obscene on moss covered beech trees between Farnham and Guildford.

Meadows are surrounded by Barbed Wire’ Herman Hesse ‘Wandering’ (North Downs Way, East of Farnham, 8 10 1)

Like 1914, 2014this has been a hot dry summer, now, it seems broken in the first few days of the new month. And suddenly, today we found ourselves confronted with small reminders of the the Leitmotive of the war.

It sounds strange, but I have started acknowledging the way that the memorialisation of war found its way into our architectural vernacular. As we climbed out from Puttenham walking, for me, for the first time West to East, I was struck by the counterpoint, repeated thousands of times across the country, between the war memorial and the church of St John the Baptist, originally Saxon, and reconstructed in the 20th Century.

There’s no question that I have become acutely aware to the dialogues between the time of war, and the time of peace. My path focused this in particular ways. Architecture was a a notable one; it’s difficult not to see a strange parity between a disused military structure and a ruined church or an abandoned farmhouse. War, it seems, reminds us, that we pass, and things change.

As the walking, the reading, the music and the drawing developed, I started to find parity between the groining of ancient roads in to the land and the excavation of trenches and redoubts. The ‘Holloways’, the ancient hidden roadways of South England took on new significance, especially when I found myself in one, under a canopy of Hazel or Yew Trees.

One of the recurring themes of the poets and writers of the First World War, not surprisingly, was soil and rock. Appollinaire wrote about the chalk of the southern extremity of the Western Front, where he was fatally wounded, and Ford Maddox Ford’s ‘Parade’s End’ is full of the nightmarish memories of the sound of enemy miners, overheard in deep bunkers further north. I found my gaze constantly wandering to my feet, as I walked the ancient Chalk road into Dover, acutely aware of the geological changes, from the sand outcroppings of the Hogs Back and Ramsgate, to the startling bands of chalk in the White Cliffs between Dover and Deal.

Ford Maddox Ford reminded me to take the weave with the natural world seriously, as reminder of the past and as a symbol. So, inevitably, the change of the seasons and the echo that offered with the change of response to the war, as it happened, as it approached, and as it receded from view, is very important. ‘Parades End’ has really offered a model of how to think, create and respond, retracing steps, again and again, seeing significance and insignificance in the smallest things.

On a walking along the Thames to my home at Wapping, all that remains of the original bridge of the London Chatham and Dover Railway, at Blackfriars-Arms of the LCBR, erected on their bridge at Blackfriars, in 1864

All that remains of the original bridge of the London Chatham and Dover Railway, at Blackfriars. After the landslip onto the South Eastern line at the Warren in 1915, it was the LCDR route to London, north and west out of Dover, which was used (despite it’s extreme gradients) for the hospital trains to London.

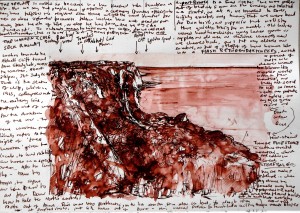

Channel Firing: Approaching Dover atop the Warren (31 7 14). With a little help from Rupert Brooke and TH White’s bestiary translation

Walking into the Dover atop the Warren elicits so many stories and ideas, from the collapse of the embankment onto the vital railway track in the early part of the war, to the realisation that this was, of course, a hill where one effectively, farmed rabbits. ‘Rabbit Warren’ is essentially tautologous.

After nearly two years with my feet on this path, it is impossible not to look at these now familiar landscapes, and the change of seasons, through the lens of the women and men of World War I, who have taught me so much. Towards Westwell, birds rising from the freshly sown field. 7 4 16

Shakespeare became an unexpected constant, on the path, and in my reflections and explorations of the real and imaginary landscapes of war and peace, and somehow, it all seemed to gravitate to ‘Shakespeare Cliff’, and the associated scene in King Lear.

Flight, and notions of flight, filled my imagination over the two years of the project, most particularly, as the First World War was the very first which was not only fought in and from the air, but the first conflinct which imagined the landscape from above. The photographs which resulted strike me as extraordinarily dissonant both from maps and from our imaginings, and I found myself, on the many plane journeys which I take in the course of a year, peering and familiar and unfamiliar landscapes from above, at night and day, and struck by this alien world of earth and vapour.

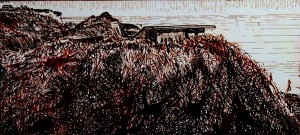

Channel Firing: approaching Shakespeare Cliff from the West, the town and Western Heights beyond (31/7-2/8/14). Apologies to Hollar

No one can spend days walking in the South of the UK without becoming more sensitive to the layers of change that time, nature and humans have wrought upon the landscape, and thus, made it. At one point, a 25 stroll in the Chilterns, along two canals in use, and one, unused, but filled with water, then across the hills back to the reminded me of this, especially, finding a favourite example, this inconspicuous earthwork near Lee Common.

Naturally, the Chilterns are geologically related to the the Downs, the northern tine of the trident of chalk which reaches east from Salisbury Plain. Many features of the landscape, natural and manmade, pertaining to war and peace, are shared, most particularly, ancient roadways and ancient earthworks. The land has been turned over and over, for millenia, and in that can be found its value, meaning, history, and destruction.Even a landscape which might be seen to be totally different from the the chalk and and sandstone downs running to Dover and Thanet, or the rich farmland of Great Stour, or the marsh of north and south Kent, shares many of the qualities of having been worked, travelled, dug, farmed, worshipped and fought over. Even the great granite protusion of Dartmoor tells similar stories of our many pasts:

‘For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground/And tell sad stories of the death of kings…’ (Richard II (A3S2)

So I am beginning to see the trenches and redoubts of the First World War in a different, or multiple perspectives. Walking the astonishing chalk roads in the Yew and Juniper woods near Merstham, on the way to Dover, on rock cut and polished by centuries of hooves, feet, and more recently mountain bikes, I am powerfully reminded that a road is, by definition, a defensive position. Or that, looked at another way, the action of centuries of travellers not only cuts down into the rock and earth, but in the process, throws up banks on either side. When we read the accounts of life at the front, all sides of the 14-18 war, it’s perhaps instructive to note that the most quotidian activity, was moving through them; the descriptions of walking, crouching, wading at the front, are, if you like, descriptions of travel on ancient roads, under extreme duress. War, as ever, simply puts the everyday into sharp and painful focus.

Talking to a young woman in Sarajevo, not long after the end of the siege, this was expressed very powerfully for me. I asked her why she risked her life, as a teenager, running along the ‘sniper alley’ by the old market, to get the cinema? ‘But normal life went on,’ she smiled. ‘We all wanted to meet at the movies. It was the same with food. I remember bursting into tears, after my mother managed to get a cabbage. I hadn’t seen a fresh vegetable for a year.’

Another aspect of the worked land, which consideration of the war throws into a brighter light, is digging, mining. Everywhere you walk, along the North Downs way, you stumble across the evidence of mining. On the top of hill, pits reveal iron workings from pre-Roman days, everywhere there are the flint diggings, so important for tools in the neolithic era, then, more recently, for facing buildings, for flintlocks. Then the hills not far from Dorking reveal the lime-mines, when cement was needed in the industrial revolution, to supply the gargantuan appetite for brick of our recent centuries. No war more than the first world war explored the necessity to dig more, to dig deeper for safety, or to undermine, or to undermine the underminers. Ford Maddox Ford’s hero, Tietjens, is tormented by the memories of the sounds of German engineers, their pickaxes somewhere below his bunker. Thinking about this, I found the following in Alan Armstrong’s, ‘The Economy of Kent 1640-1914’:

‘I have seen men, with a life line fastened round their bodies, securely tied to an iron crow bar driven into the ground at the top, and some few yards from the edge of the chalk cliff. There would be several men working at different heights quarrying the cliff, which would sometimes crumble beneath their feet.’

And of course, everywhere, especially with the harvest in; ploughing. Yesterday, we got lost, as the path we were seeking had been temporarily obliterated by the necessary work of the farmer after a good harvest. Edward Thomas put the tragedy best:

‘This ploughman died in battle’

Visitors to England, arriving and departing from the UK in peace and war filled my thoughts. One of these was the Bohemian artist and cartographer Wenceslaus Hollar, who came to England to work for the Duke of Arundel, and was sent to draw the fortifications of Tangier, newly acquired following the marriage of Charles II to the Catherine of Braganza. And of course, Hollar’s depiction of Dover castle stuck in my mind, especially when I was drawing the First World War defences on the cliffs to the west of Dover. Hollar, it seemed, took hold of my pen, and helped me a lot.

My wife, the writer Malene Skaerved, has been a constant companion on this exploration. J M W Turner became a constant topic on the walks. Firstly, because, of course, he is both a Kent (Margate) and a London (Wapping, where we live), and secondly his work was forged in the tragedy of the Napoleonic Wars, and in the opportunity that he took, in the brief armistice, take the packet from Dover, and to visit the Louvre.

Documenting the walk. One of the crossections I have made-this one showing a segment walked from Mersham to Guildford (East to West). It records a deliberately non hierarchical range of things, from 1890s fortifications to wildlife.

The redundant lines of fortifications, stretching from the Cliffs at dover, along the chalk hills to Guildford and beyond, were and are a constant in this project. There’s only one unifying feature, a reassuring one: whether it’s the redoubts of the 1880/90s at Dorking, the WWII pillboxes east of Box Hill, or the WWI fortifications and acoustic mirrors all along the escarpments-Nature will have her way, stone, brick, iron, steel and concrete, are all shattered by moss, frost, root and twig.

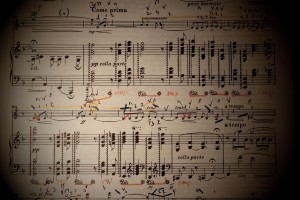

The ‘road to war’, just like the paths too and from Dover, have, for me, become thickly populated with the voices. If the project had a ‘theme song’, it would have to be this, composed by Sir Edward Elgar in the Spring of 1914. ‘Sospiri’ (Sighing)

Edward Elgar-Sospiri (1914) (W H Reed Freundschaftlichst zugeeignet)

Peter Sheppard Skaerved-W E Hill & Sons 1901, Tubbs 1878 (Presented to the composer)/Roderick Chadwick-Piano

<

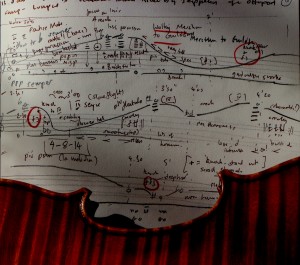

A miraculous piece: my score of ‘Sospiri’ with Elgar’s extraordinarily detailed pedalling and implied portamenti highlighted

There was so much different music emerging in 1914; so much of it filled with forboding and anxiety. I am fully aware that this is said with the benefit of hindsight. But hindsight is all that we have. Here is Anton von Webern’s ‘Six Bagatelles’ in a performance which I gave with my quartet, with paintings and photographs made and taken as the project grew. Some of the objects (the Red Cross symbol, the flechette) were seen in the Dover Museum exhibit, so this is one of my first responses, as ‘Channel Firing’ began to grow.

If I am honest, I had spent many years resisting Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach. But this extraordinarily prophetic poem found its way into the heart of the project, particularly when my wife Malene, and son Marius, joined me on long stretches of the wonderful paths along the chalk hills to and from Dover.

‘Ah, love, let us be true

To one another!’

… never before seemed so true, so touching.

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night. (Matthew Arnold ‘Dover Beach’26/12/15

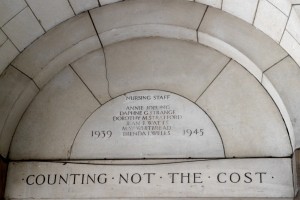

I have been thinking about the astonishing work of the nurses, a profession which barely existed, even in 1914. Juliet Nicholson’s astonishing ‘The Great Silence’ reminds us that there were barely 5 nurses per 1000000 of the population in 1900. Today, I noticed this in the gatehouse of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Smithfield.

Memorial to nurses who died in conflict from ‘S Barts’ 18 10 14

Interesting, the quote is a Jesuit one, taken from St Ignatius’s ‘Prayer for Generosity’

Lord, teach me to be generous.

Teach me to serve you as you deserve;

to give and not to count the cost,

to fight and not to heed the wounds,

to toil and not to seek for rest,

to labor and not to ask for reward,

save that of knowing that I do your will.

Living in Central London, next to one of the last surviving Bomb Sites, the terrible beauty of aerial warfare is all about me. One of the photos on the film above I took by ‘Cleopatra’s Needle’ which was badly hit in a Gotha bomber attack in 1917. A strange consonance emerged, between the abstraction of musical scores, the painting which I was doing, and the exquisite reconnaissance photos taken from the sky above Dover.

Marker in the roadway by the Chapel of Lincolns Inn, marking the spot where a bomb exploded dropped by a Zeppelin on the 13th October 1915. Photo. P Sheppard Skaerved 15 10 14

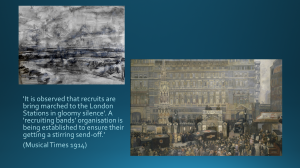

The September 1914 issue of the ‘Musical Times’ concerned itself with some of the pscyhological effects that the war was expected to have: ‘The intense obsession of the mind’-‘a sort of stupor and a feeling that the ordinary concerns of individual life are jejeune and insignificant’. And the following, which in retrsopect, is touching, or heart-breaking, or both: ‘It is observed that recruits are bring marched to the London Stations in gloomy silence’. A ‘recruiting bands’ organisation is being established to ensure their getting a stirring send-off.’ This immediately reminded me of the painting by J Hodgson Lobley in the Imperial War Museum collection. Casualties from the Battle of the Somme (1916) arriving on the trains from Dover at Charing Cross. A very different ‘gloomy silence’, tragically.

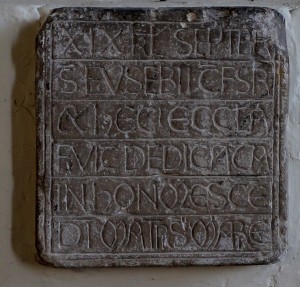

Foundation Stone (possibly 12th Century-Postling Church of St Mary and Radegund. Walking the Pilgrim Trail Winchester- Dover July 31st 2014)

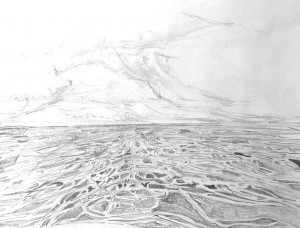

The sea has been a constant in this project: the symbolism for this tragic conflict is overwhelming. It is a place to cross, to conflict, to home, to escape, to death. The tide and currents mercifully wash away human mistakes and cruelty, and it is a source of life and energy.

Enrique Granados (who died in the torpedoed SS Sussex) working on piano rolls in New York (1915) and Fritz Kreisler and his Wife, Marie, in Uniform at the beginning of the war

Enrique Granados’ ‘Danse Espagnole’ was transcribed by the great Austrian violinist Fritz Kreisler, who wrote a heart breaking account (quoted above) of his time at the Eastern Front. Granados died off the Kent coast, on his way back to Spain from making piano rolls in New York (pictured at top), and giving a recital at the White House for Woodrow Wilson. He and his wife were passengers on the SS Sussex, which was torpedoed shortly after it left Folkestone in 1916.

Enrique Granados-‘Danse Espagnole’

A morning in All Hallows by the Tower. The Saxon Chapel, underground, and a 15th Century sculpture of At Anthony of Eqypt. Two small miracles. 21 7 14

Everyone sang

Everyone suddenly burst out singing/And I was filled with such delight /As prisoned birds must find in freedom. /Winging wildly across the white Orchards and dark-green fields; on-on-and out of sight. /Everyone’s voice was suddenly lifted, /And beauty came like the setting sun: /My heart was shaken with tears; and horror /Drifted away … /O, but Everyone Was a bird, and the song was wordless; the singing will never be done. (Siegfried Sassoon)

Walking west from Guildford.Two readings of Ancient Yew trees in the graveyard of St Mary’s, Bentley, Hants

Thirty Miles east from Guildford, on the North Downs Way and St Swithins Way. Tracks in the corn. 730am, from East Warren. 9 July 2014

Crossing the zero meridian on the Pilgrims Way, a mile south of Botley Hill. With Malene Sheppard Skaerved, walking Redhill to Chelsfield. 27 6 14

The year that the war broke out inspired a wide variety of responses-from the heroic to the mocking. I am not quite sure where to place Erik Satie’s extraordinary 3 pieces from 1914 . This piece has been something of an obsession of mine for many years. It is Satie’s only published work for violin and piano, although there is also another (untitled movement) for the combination. The piece is one of Satie’s funniest, and also most melancholy, and it always feels to me that the composer was playing a Magritte-like game with language. The score is littered with playfully poetic performance instructions, ranging from ‘dry and distant bones'( which always put me in mind of T S Eliot’s mock-surreal’I should have been a pair of ragged claws/Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.’) to ‘crest-fallen'(penaud), after a violin cadenza which is marked ‘with enthusiasm’. The exquisite chorale which begins the work is marked thus:

‘My Chorales equal those of Bach, with this difference; they are less numerous and less pretentious’

Satie-Choses vues à droite et à gauche (sans lunettes) 1914 (Choral hypocrite-Fugue à tâtons-Fantaisie musculaire) Workshop recording. Peter Sheppard Skærved and Roderick Chadwick.

Erik Satie- Choses vues à droite et à gauche (sans lunettes) 1914 (Published 1916)

Choral hypocrite

Fugue à tâtons

Fantaisie musculaire

Peter Sheppard Skaerved-Violin

Roderick Chadwick-Piano

‘Channel Firing project’

(Recording Outtakes-unedited 30 10 14 St Michaels Highgate)

Engineer-Jonathan Haskell (Astounding Sounds)

I have been fascinated with these three pieces for my entire career. returning to play and study them with ever-increasing delight. For all their apparent simplicity, this set works on so many different levels, that I find new entry points, new areas of exploration. The pieces can be ‘read’, even shorn of music, as an unheard poem, read silently in the performance directions.

Grave

le main sur la consicence

très en dehors

ralentir avec bonté

Fugue à tâtons

dans un candour niaise mais convenable

du bout des fonts du fond

tranquille comme baptiste

en clignant de l’oeil

avec tendresse et fatalité

les os secs et lointains

partez d’un seul coup

en élargissant la tête

large de vue

Fantaisie musculaire

un peu vif

le dos voûté

avec enthousiasme

très penaud

froidement

I will leave it to Apollinaire, who died from his wounds at the end of the war, to respond. Ocean of Earth I built a house in the middle of the ocean Its windows are the rivers which flow from my eyes Squid groan everywhere as they stick to the walls Hear their triple hearts and their beaks tapping the glass Humid House Hot House Fast Season The Season that sings Aeroplanes beat the eggs Attention-they are going to cast their anchors Watch out for the ink they are ready to throw It would be best, if you varnish the sky The goat-leaf of the heavens The palpitating earthbound squid But then we are our more and more our own gravediggers Pale squid on the waves of chalk, squid of the pale beaks You know the ocean around the house Which never rests (Apollinaire)

‘I should like the words ‘alien’ and ‘foreigner’ to be banised from the language. We are all members of the same family’ (Charlotte Despard 1917 -born in Ripple Vale, sister of Sir John French)

Walking from Ramsgate to Dover: We found a lovely lunch in Sandwich in a cafe near the Guildhall, with its astonishingly preserved 17th Century Courtroom. We ate fish pie and home grown vegetables under a wonderful ‘bunte’ of beams and rafters, not a few of them, clearly ‘salvaged’ from the many churches, either during the Reformation, or when they fell down in the 17th Century. But it was a 20th century building (albeit half-timbered) which caught my eye, in the square outside. The East Kent Road Car Company was formed in the summer of 1916, from a number if competing bus companies in the area (most of which had been granted licences two years earlier to serve the burgeoning tourist trade, which had blossomed in the long hot summer of 1914). Shortages of parts forced the amalgamation, and, come the end of the war (Christian Wolmar’s ‘Steam and Speed’ had already alerted me to this), the company was able to expand with ex-military vehicles, suddenly in surplus; this began the British trucking boom, from which the railways never recovered.

The ‘Waiting Room for Passengers’ is charming; though no longer in use for its original purpose (there’s a huge snooker table inside at the moment), it is beautifully preserved. It’s a testament of the nostalgia for a lost medieval age which spurred the building of myriad ‘half-timbered’ suburban semi-detached houses in the interwar years.

Walking Ramsgate, Sandwich, Deal, Walmer, Dover :St Peter’s Church, Deal. Wooden Cross, the grave marked of Major R D Harrison ‘Killed in Action 16th September 1917’. The two mottos, ‘Ubique’ and ‘Quo fas et gloria ducunt, on the cross, tell us that he was either a member of the Royal Artillery or the Royal Engineers. ‘RFA’ confirms that he was a member of a ‘Royal Field Artillery’ brigade

This was a long walk rich in layered history, and astonishing beauty. It’s fascinating to me, that as we walked south, over the traditional landing sites for the Saxons and St Augustine at Ebbsfleet, the Roman and (secret) First World War Port at Richborough, we first found ourselves confronted by a more modern relic. Crumbling gracefully into the sea, wildlife and marsh reclaiming it, the almost forgotten Hoverport at Ramsgate. This was mooted, in my childhood, as a perfect example of military technology-landing craft, hovercraft technology, finding a peaceful use (though no one who was ever close to one of these hovercraft would say that!). Petrol prices put paid to that. and now, the terminal is a natural wonder-the runways and marshalling spaces slipping into the sea, a footbridge to nowhere from the sandstone cliff at the west. Ozymandius, again.

One of the ‘runways’ at the old Hoverlloyd Terminal at Ramsgate:It’s clear that, with the departure of the terminal, Pegwell Bay is returning to the state described in my 1863 ‘Bradshaw’:

‘No one would think of stopping a week at Ramsgate without going to Pegwell Bay, where the savoury shrimps and country-made brown bread are supposed to have been brought to the very highest degree of perfection’

It was in the shattered church of St Peter in Sandwich, that we found the haunting memorial from 1917 (see above). This palimpsest of a building, which even includes the remains of a Dutch chapel built by my Hugenot forbears, offered a moment of tenderness, the tomb of a 14th century couple; local worthies, probably merchants, their heads angled so they could see the altar from their chest-tomb.

” I last saw him at Charing Cross. We were both casualties. All the way from Dover, he had moaned one word: ‘Lunnon’. At Charing Cross they laid his stretcher beside mine. He was half conscious, Suddenly he revived and called out, his voice boyish and jolly: “Good ol’ Charing Cross!” and fell back dead.”

-the era before. Some hours in Tate Britain, lost in wonder at the richness of the paintings running up to the war. We went backwards, beginning with Levinson, and Spencer, and Gertler, and Wyndham Lewis, and then were swept off our feet by Lazlo, Lavery, Millais, Watts, Hunt, Rossetti, Leighton, Tissot, Landseer, Burne Jones. Sat and talked and drew for a long time in front of Tissot’s 1874 ‘the Ball on Shipboard’. The awning to protect the partygoers from the summer sun is made from the draped flags of the German Navy, Britain, Austria, America, Belgium, France – dressed overall, meant all the flags of all the nations, and some flags which would cease to exist. There would be very different embarkations in the future, and my drawing, unwittingly, came to reflect that, the more that we talked and looked.

A different Coast. Walking around Faversham, Oare, Conyer, and Sittingbourne. This far from straight walk not only exposed me to a very different landscape than the Downs and Dover, but that landscape, which has been honed, torn apart and controlled by humans for centuries, quivers with its exposed history. There’s no foliage, no hedgerows, no valley to conceal the stories. One aspect which I have not yet broached in this blog is the natural world. The reaction to the war, from poets, composers, artists, and letter writers, was essentially, a pastoral one. And that has not been lost on Malene and I as we have been able to walk the Pilgrims way in a summer of astonishing natural glory.

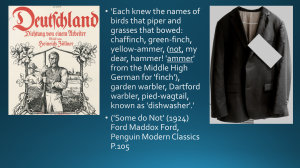

It’s not just a counterpoint, or even a counterpose, but one of the threads running through the experience. Yellowhammers have pursued us from hedgerow to hedgerow the whole length of the walk. Historically, this bird was hunted for its assumed association with the devil, a practice which continued up till the beginning of the Twentieth Century. This may have been a result of its sulphuric colouration, or, more likely , and idea that the black/brown squiggles on the eggs might be some diab0lic script. However, by the time Ford Maddox Ford came to write the first the four books which make up ‘Parades End’ (‘Some do not…) in 1922-3, the association was more benign, and flagged up a natural association with German culture which would be lost in the fog of war.

‘Each knew the names of birds that piper and grasses that bowed: chaffinch, green-finch, yellow-ammer, (not, my dear, hammer! ‘ammer’ from the Middle High German for ‘finch’), garden warbler, Dartford warbler, pied-wagtail, known as ‘dishwasher’.’ (‘Some do Not’ (1924) Ford Maddox Ford, Penguin Modern Classics P.105

As we walked from Oare towards Harty Ferry, clouds of Yellow-ammer, and Pipits swirled around us. It was very difficult to even imagine that we were in the area affected by the disastrous, and, to this day, mysterious 1916 explosion at the Explosives Loading Company factory (2 April), 1916, which took the lives of 109 men and boys. But, a tragic aspect to the North Kent coast in the First War, is the number of lives lost, on ships and factories, from here to Sheerness. The open-skyed beauty of the place renders it all the more heartbreaking. Down on the shore north of Luddenham marshes, I found a natural wonder, the skull of a porpoise. This was the climax of a day when nature seemed to be conspiring to push away the follies of mankind. Here it is, and I confess to wonderment that I can take a train that takes just over an hour from my home in Wapping, and find this creature, majestic even in death.

Idea well up from the walk to, and circumscribing Dover and Kent. One of these very much in my mind this morning, as my wife and I spent time in front of an imaginary landscape, by the Dutch artist, Philip de Konnick (1619-1688).

Little is known of de Konnick’s life, but his picture suggests to me, that after the Restoration, he may have taken the boat to Kent, and seen the counterpoint of lowland and downs of the Stour Valley. But, as is so often the case with the great landscapists of the time, particularly Ruisdael, one can see a prophetic cast in the land, as prophetic as Arnold, of how the fictional Christopher Tietjens, in Ford Maddox Ford’s ‘Parade’s End’, describes the land, remodelled by modern war.

‘A dawn-land road, with some old thorn trees, they only grew really in Kent. And the sky coming down on all sides. The flat top of a down!’ (‘A Man Could Stand Up’ – Parade’s End, P.604)

The text, irrestible as my reading of this landscape of dikes and distant hills, was of course, Matthew Arnold’s ‘Dover Beach’, or rather, it’s prophetic ending.

‘Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.’

He wrote that 65 years before the war broke out, inspired by the ‘long line of spray/Where the sea meets the moon-blanch’d land,’ beneath the ‘cliffs of England’, ‘glimmery and vast’.

Hospital Ships, Cleopatra’s Needle Back on firm ground, and enraptured by the experience of sailing to and from Dover. By complete chance, today, we found ourselves today onboard HQS Wellington. A thought-provoking exhibit on the hospital troop ships of the war. This picture is inspiring me, especially as I have just spent the past two weeks playing 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th Century music on board ship for the past two weeks. And reading a letter from William Lomnor to John Paston I, written on the 5th May 1450, I ran into the account of the violent death of the Duke of Suffolk, on board ship off Dover. I am unable to resist the layers of history which the 1914-18 conflict seem to set vibrating. This horrific image is just the latest.

‘And in the sight of all his men he was drawn out of the great ship into the boat, and there was an axe and a stock; and one of the lewdest of the ship bade him lay down his head, and h should be fair ferd {dealt} with, and die on a sword; and took a rusty sword, and smote off his head within half a dozen strokes, and took away his gown of russet and his double of velvet mailed, and ladi his body on the sands of Dover. And some say his head was set on a pole by it, and his men set on the land by great circumstance and prayer. And the sheriff of Kent doth watch the body, and sent his undersheriff to the judges to weet what to do, and also to the king. What shall be do further I wot not, but thus far is it…(The Paston Letters, Ed.Norman Davis, OUP 1983, Pp.27-8)

But back to the Thames. Half a mile from the HQS Wellington, one of the most enduring relics of the destruction of 1914-18. On the night of the 4-5th September, 11 Gotha Bombers attempted the first night raid on London. Navigation was largely a matter of luck, and only five of the planes that made the attack got to London, of the nine that made it acrros the channel. The others found their way to Suffolk, to Margate and to Dover. One of them attempted to hit Charing Cross station, and got very close, as the Needle is only a couple of hundred metres away. The damage was extensive-killing two people on a passing tram (including the driver), and ripping open the roadway, exposing gas and electricity lines, as well as the District Line, running a few metres below. The scars in the granite plinth, and to the bronze sphinxes remain, offering a mild warning of what was to come, quarter of a century later.

Malory, Dover

‘Then there was launching of great botis and smale, and full of noble men of armys’ Malory.

As I have said before, the layering of histories, the making and telling of -stories, is something which fascinates me, and constant return to the Arthurian myth is one which is unavoidable in Dover, and underlay the ‘going to war’ in 1914. Generations had been raised on Tennyson’s Idylls of the King , and in Germany and Austria, Wagner had fanned an Arthurian flame high with the Yggdrasil and Ossian. Laurence Binyon’s For the Fallen is just the latest turn of a wheel of stories, turning back through the Morte d’Arthur, to Henry the Fifth, to Malory, Geoffrey of Monmouth, to the Homeric forbears that nearly every nation claimed. The ‘topless towers of Illium’ could still, it seemed, be glimpsed, from the White Cliffs.

‘They went with songs to battle, they were young, Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted,. They fell with their faces to the foe.’ (Binyon, The Four Years, (1919) London, Elkin Mathews, P.42)

Sir Thomas Malory (ca.1480) elaborated on the earlier ‘Mortes d’Artus’ and explicitly begins the ‘last battle’ between the forces of Arthur and his son, Mordred at Dover, before running his the armies west along the downs to doom in the west country. This came to mind last week, running into a replica Hansa ‘Cog’ on the German coast near Rostok, and a fatefilled sky.

‘And so as sir Mordred was at Dovir with hys oste, so cam kyng Arthur with a great navy of shyppis and galyes and carykes, and there was sir Mordred ready awaytying uppon his londynge, to lette hys owne fadir to londe uppon the londe that he was kynge over. /Then there was launching of greate botis and smale, and full of noble men of armys; and there was muche slaughtir of jantyll knyghtes, and many a full bolde barowne was layde full lowe on bothe partyes.’ (The Morte Arthur, Bk.XXI, P.709, Lines 6-12, OUP, 1971)

‘…five moons were seen tonight;/Four fixed, and the fifth did whirl about the other four in motion’ 23 12 15

“Nothing is to be written on this side except the date and signature of the sender. Sentences not required may be erased. If anything else is added the post card will be destroyed….I am quite well…I have been admitted into hospital [sick/wounded] [and am going on well/and hope to be discharged soon…I am being sent down to the base…I have received your [letter dated/telegram/parcel]…Letters follow at the first opportunity…I have revieved no letter from you [for a lately/for a long time]…Signature only…Date” (Form A2094. Field Service Postcard , ‘whizzbang/quickfirer’)

… some ideas about the Black Death, and Malaria in Kent in the War. This issue arose at the onset of hostilities, as the possibility of infection being brought home by soldiers returning from Eastern Mediterranean. The fears actually proved justified; 500 people in Kent were infected, althoughnone died. Up until the end of the 19th Century, the link between Malaria and the Mosquito was unsuspected until the pioneering work of Ronald Rose. Ever since the first reported instance of the contagion in the 16th century, inhabitants of marshy areas in the UK, had been at risk. In many areas, Opium, from poppies specifically cultivated for this purpose was introduced into the died, in an attempt to stave off the disease. It was not uncommon to find large percentages of Marsh or Fenland areas in the East and South of England to be addicted, and pubs offer opium-laced beer as a pre-emptive. Rose (before the war) created ‘mosquito brigades’ in order to clear blocked and stagnant pools and ditches. These brigades became de facto military operations come the war (the Imperial War Museum has hundreds of images painstakingly documenting their wartime work in Kent).

Walking around the (man-made) lowland areas of Kent, in the Stour Valley, the North coast, it’s impossible to not see the risk, with, at this time of year Spirogyra-clogged ditches and dykes like the one above. Fascinatingly, Malaria was being used among soldiers as a treatment for the scourge of syphillis. Sr Alfred Jones, Ross’s rival in the research, discovered the effectiveness of this treatment whilst researching an alternative method of preventing the spread of Malaria, which involved well-aired, un-crowded accommodation, the clearing of cluttered farm-buildings and outhouses. The IWM website provides plenty of evidence that both techniques were being put to use. However, the word ‘Malaria’, literally ‘Bad Air’ points to a history that looks back beyond the first cases of the disease in the UK, and to the old fear of infection through ‘miasma’. Shakespeare is full of it:

‘O, when mine eyes did see Olivia first,/Methought she purged the air of pestilence.’

Far from Dover, steaming off the coast of Gotland, reading the ‘Song of Lewes’, which dates from the early 13th century:

‘’Thou shalt rider sporeless o thy lyard [grey horse]/Al the ryghte way to Douere ward; Shalt thou neuermore breke foreward, Ant that reweth sore.” (Song of Lewes Lines 39-41)

I find that these Middle English texts help me to find a ‘way in’ to thinking about Dover in 1914-19. I think that the reason is, that the war footing returned people to a phlegmatic outlook which reminds me of the outlook of the middle ages. Phil Eyden’s ‘Dover’s Western Heights in the First World War’ is providing a fascinating counterpoint to this reading. I am very grateful for his research and insight. Eyden’s account of the death of Private William Burton, on November 5th 1915, has an almost Chaucerian quality; Burton’s body was discovered at the base of Shakespeare Cliff:

‘A 34-year old quiet, introspective man who had not been passed fit for active service, […] he had disappeared whilst setting up targets on the firing range, and a search party was sent out to look for him. Burton was still alive when discovered, but died whilst being rolled over. A note was found in his pocket stating “Unfit! Unfit! Cannot be murdered by Germans. These unmerciful and inhuman beasts. May my soul rest in peace out of the way.’ (P.30 ‘Dover’s Western Heights in the First World War’, Phil Eyden, Riverdale Publications, Dover 2014

The score of the new piece, with the most British of violins, my beloved Hill 1903

The score of the new piece, with the most British of violins, my beloved Hill 1903

Acoustic Mirror (Early Warning System) 1917 on the cliffs between Dover and Capel Le Ferne. Walking Wye to Dover 31 7 14

The acoustic mirror has put me in mind of the ‘Prophecies of Merlin’ from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s ‘History of the Kings of England’: Merlin:

‘In that time the stones will speak./The over which men sail to Gaul shall be contracted into a narrow channel A man on any one of the two shores will be audible to a man on the other, and the land mass of the island will grow greater./The secrets of the creatures who live under the sea shall be revealed, and Gaul will tremble for fear.’

Chestnuts from the Autumn 2014, and a German Propaganda poster ‘Collect Acorns and Chestnuts’. By the end of the war, Germans were starving, the result of the British Blockade

Autumn: collecting horse chestnuts in Wapping, I was reminded of the following announcement in the KENT MESSENGER ’27th October 1917 URGENT APPEAL FOR CONKERS – 200,000 tons of horse chestnuts are called for in appeals published in local papers.The horse chestnuts will be sent to drying stations, where starch will be extracted from the nuts.Acetone from this starch will be used to produce cordite, a vital component in munitions.Miss Baillie-Hamilton, of Greenway Court, Hollingbourne, has been appointed to organise conker collections on behalf of the Department of Propellant Supplies. Children from local schools respond enthusiastically to the appeal. (Kent Messenger 27 10 1917? Conker fighting is not what it was. I remember the schoolyard of my childhood, carpeted with broken conkers. I would commandeer my father’s tools to drill holes in the perfect nut. However it strikes me that there may be, just may be, a link between the apparent military application of the humble, inedible conker, and it’s perceived value as a weapon of war. Many of the references to the game until the 20th century refer equally to other, more edible nuts being used, so I wonder whether the iniativ spearheaded by Ms Baillie-Hamilton in Hollingbourne, drove the imagination of schoolchildren, rather more than it had any quantifiable result. The end of October would seem very late to think about it (and if collection was being organised for the following year, it would have been too late to be of benefit). It also brings to mind Wordsworth’s analogy between nut-gathering and the rapine of war, written in the year of the battle of Aboukir Bay: ‘Then up I rose, And dragged to earth both branch and bough, with crash And merciless ravage: and the shady nook Of hazels, and the green and mossy bower, Deformed and sullied, patiently gave up Their quiet being[…]’ (William Wordsworth, ‘Nutting’ (Lyrical Ballads) written 1798

Vigil. Moons. Jupiters. De nomenclaturis Romanis. recens Danice factis, pari Graecarum 1594, (23 2 16)

Crossing the water; the wound-dresser

It’s increasingly impossible for me to disentangle narratives of past and present, fact and fiction, writing and music, as I bring this project together. Composer Robert Saxton reminded me that Edward Elgar’s father was a Dover Pilot. Here’s one of his professional descendants, alongside our ship in the Channel, two weeks ago.

Dropping the Pilot. August 10th.

In order to distinguish between sea journeys taken for war and those for religion, the Anglo-Saxon chroniclers of the 7th century simply used direction. In 616 Bishop Laurentius of Canterbury (he had succeeded Augustine, whom he had accompanied on the orginal mission sent by Pope Gregory) ‘He wolde su?ofe sae’. ‘South over the sea’ implied St Iago. He was dissuaded by St Peter in a dream. (Peterborough MS). The enlightenment introduced a very different kind of pilgrimage, initially for the privileged; crossing the channel in the cause of Art and Culture, even to become ‘inglese italiano’. By the end of the 19th Century, the pursuit of culture, meant, very much, Germany. Young men and women sought out the universities and art schools of Berlin, Munich, Leipzig, for their self improvement. This would be permamently derailed by the 1914-18 war. For musicians, Leipzig and Berlin were the goals. Elgar’s epochal violin concerto had been published, naturally enough, in Leipzig, in 1910. And then, this afternoon, I found myself, speechless before CRW Nevinson’s French Troops Resting(1916) at the wonderful exhibition ‘Art from the First World War’ at the Imperial War Museum.

Ecce Homo-an hour with Nevinson. 26 8 14 IWMSitting with Chrisopher Nevinson at the Imperial War Museum

And Malory’s description of the burial of Gawayne and the compassion of Arthur on the ‘Day of Destiny’ was back with me:

‘And so at the owre of no one sir Gawayne yielded up the ghost. And than the kynge lat entere hym in a chapel within Dover castell. And there all the men may se the skulle of hym, and the same wounde is sene that sir Launcelot gaff in batayle. […]And than the kynge let serche all the downys for hys knyghtes that were slayne, and entered them; and salved them with soft salve that full sore were wounded.’ Sir Thomas Malory-The Morte Arthur ‘The Day of Destiny’ Bk.XXI Pp.710-11

On the HQS Wellington two days ago, another reminder of the Channel, and the hospital ships shuttling the wounded across from France. One of these was the paddlesteamer ‘Viper’, which was requisitioned for this purpose. When the ship was scrapped, the elegant stair case was salvaged for the ‘Wellington’ as she took up ceremonial duties on the River Thames.

Responding to van Konnick, and silent crowds at Charing Cross as the wounded from Somme arrive from the Dover Train

(11-12 December 2015) ‘Materialschlacht’1915-‘I am not a delegate’-Labour MP Jim Fitztpatrick (Letter to party members), voting ‘Yes’ to bomb in Syria 2015

‘bo’: Danish, ‘live’ (linked to old Norse, ‘Bua’-dwelling …. ‘bod’: Cornish, ‘Dwelling, early toponym from ‘bos’, ‘to be’. And a night practising Jeremy Dale Roberts 1 12 14

‘We were pulled out of bed at 5 am on the Sunday, and told that we started at 9. We marched to Dover, highly excited, only knowing that we were bound for Dunkirk and supposing that we’d stay their quietly training for a month. Old ladies waved handkerchiefs, young ladies gave us apples and old men and children cheered, and we cheered back, and I very elderly and sombre, and full of thoughts of how human life was a flash between darknesses, and that x percent of those who cheered would be blown into another world within a few months; that they all seemed to me so innocent and pathetic and noble, and my eyes grew round and tear stained.’ (Rupbert Brook-letter 1914)

What in our lives is burnt In the fire of this? The heart’s dear granary? The much we shall miss. Three lives hath one life- Iron, honey, gold. The gold, the honey gone. Left is the hard and cold. Iron are our lives Molten right through our youth, A burnt space through ripe fields, A fair mouth’s broken tooth. (Isaac Rosenberg 1916)

Walking through the lush marshland between Ferry Crossing and Canterbury, we came across a group of very happy horses, up to their fetlocks in water, eating in the reeds. Upon looking at one of the last pictures I took during that day in Canterbury, I found this this (click on the picture to get a better look):

I confess that I had not noticed it , when I was taking the picture of the Royal East Kent Yeomanry memorial in front. Over the past month or so, we have been walking along ancient roads, which for the majority of their existence were dominated by the horse; bearing soldiery, pilgrims, wool merchants, pulling farm machinery and produce … It is estimated that at least 8 million horses died on both sides in the war. I think that it’s only fair that I post the whole of the quote from the book of Job which has been affixed to the horse trough. It’s missing, but, tragically, very much in the air:

‘He paweth in the valley, and rejoiceth in his strength: he goeth on to meet the armed men.'(Job 39:21)

I need say no more.

In Faversham church, preparations were underway for the annual Hop Festival. The lady who we talked to was not so pleased that ‘Shepherd Neame’, who usually sent a Barrel to place in the Nave for the festival, had sent, instead, what appeared to be (her words), a ‘shop window’, with lots of bottles of beer. Nevertheless, they’d also sent enormous mounds of fragrant hops. At the beginning of the war, it was agreed that the pubs which coordinated the Hop picking in Kent, would use their organisational skills to serve as recruitment centres, but only after the harvest was in.

This project has pushed me closer to the elements, to the earth. Spend long enough on any path, and its history, memories and geology, will become very real.

All that remains of the original bridge of the London Chatham and Dover Railway, at Blackfriars. After the landslip onto the South Eastern line at the Warren in 1915, it was the LCDR route to London, north and west out of Dover, which was used (despite it’s extreme gradients) for the hospital trains to London.

I have to acknowledge the debt which I owe to the artists and writers of the First World War. Their imagination and inspiration has surrounded me at every turn, and spending time with their work has helped me out of many an impasse. Here’s an example.

I have realised that much of the past month or so has been influenced by conversation with, and the work of my friendPatricia Hampl. Her ‘Spillville’ is a visionary approach to Dvorak in Iowa, and opened my ears and eyes to music that I thought that I knew. She notes:

‘I suppose that makes this trip a pilgrimage: in the footsteps of”

In his book, ‘Japanese Pilgrimage’, the American writer Oliver Statler noted that the important difference between European and Japanese notions of pilgrimage, was that the Japanese tended towards circular pilgrimages, not linear ones. This made a big impression on me when I read it in my early twenties, and helps now, with examining how I/we are looking at, playing with, travelling along the many paths which this anniversary has opened up. I realise that I am unconsciously modelling the longing which grew, in soldiers and those at home, for the lost hot summer, the ‘pastoral idyll’ of ’14, which preceded the war and the onset of colder, wetter realities.

‘Arrived at Dover in order to embark for France, but was detained there by a foolish accident which happened on the road, for having left my sword, that necessary passport for a gentleman on the continent, I thought it of consequence to enough to remain at Dover till I recovered it which was not till Wednesday night. However this delay gave me the opportunity of seeing the castle and of lounging about the town with a person very dear to me who had accompanied me thither’ (Charles Burney 1770)

German propaganda; patriotic song. My jacket, set up with an envelope as if for an execution, Glasgow September 2014

The British executed 4 of their own in 1914, 55 in 1915, 95 in 1916. I am not sure that the figures reflect an increase in savagery or draconian sentencing; rather that the proportion of soldiers suffering from what we would now recognise as PTSD, had increased, exponentially, as the war went on. In the whole war, the Germans executed 48 soldiers. But, it was Adam Hochschild’s (‘To End All Wars) description of the routine, designed to ensure a shot to the heart, which came to me as I hung up my suit; I’ve illustrated it, and it’s hanging on my wall now.

‘A officer pinned a white envelope over each man’s heart as a target’ (Hochschild P.243)

The Kent born poet Siegried Sassoon, says it better than I can:

‘You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you’ll never know

The Hell where youth and laughter go.’

My indignant reaction to the ceramic poppies which fillled the moat of a castle not 10 minutes walk from my front door in Wapping, reminds me of the straight line which was drawn, between Spy, Coward, and Conscientious objector. After all, it was the fraudster, liberal MP, and propagandist, Horatio Bottomley, who called for ‘COs’ to be shot in the Tower of London. It’s worth reminding ourselves that the Tower of London was where Germans accused of spying, 17 of them, were shot during the war.

Walking East out of Wye, the hillside was covered in thistles, particularly the Slenderflowered Thistle (Carduus Tenuiflorus) flocks of Goldfinch (Carduelis Carduelis). Both of them symbols of the Passion, of the thorns and thistles which made up the Crown of Thorns, the Goldfinches which feed on the flowers-the Latin name, means ‘Thistle-eater’. A reminder that the flowers and animals which have surrounded me on this journey have complex webs of imagery. A flower, of whatever colour, means so many things. The Poppy is not only used by Hypnos to bring sleep, or Morpheus to bring night to the land. It is also a symbol of the Last Supper, as it grows in the cornfield, amongst the grain which will eventially become transformed, through trans- or consubstantiation, into the body of the Saviour.

So to finish from the stunned years after the war, Delius’ ‘Lullaby for a Modern Baby-to be played or hummed’ (1923), filmed in rehearsal at Edvard Grieg’s house in Bergen.

Posted on March 28th, 2016 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved