And so I come to Friday evening, and gratefully reach home after a ridiculously interesting, stimulating week, filled with astonishing collaborators/friends, wonderful conversations, ideas and inspiration at every turn. In the past four days however, these have acquired a tighter focus, that of artistic ownership, and the fine line between freedom and intrusion. Where to begin? Perhaps, just perhaps, the best place is Palladio.

Day one

On Tuesday, I took the short walk from the Royal Academy of Music on Marylebone Road, down to Brewer Street, in Soho. It was a perfect afternoon to walk across a little bit of London, the light showing me new architectural wonders on streets which I thought that I knew very well.

I was running early for my appointment, so was open to distraction, which came my way in the shape of the glorious RIBA(Royal Institute of British Architects) Building on Great Portland Street. I can never walk past, without being drawn in, and it was no different Tuesday, except that upon entering further diversion offered itself, in the shape of the current exhibition reflecting on the influence of Andrea Palladio ‘Palladian Design: The Good, The Bad and the Unexpected’.

Like him, or hate him, Palladio is part of our visual lexicon, just as Shakespeare, Luther, Bach and Mozart, formed our linguistic and musical languages. We are their children. This compact exhibit reflected on that. I confess that I was not in the mood for the more recent reflections of Palladio, but was drawn to his astonishing drawings, and to the spectacular architect’s model for Gibbs’s St Martin in the Fields’, a church, which I happen, oddly to remember, cost £33,000 to build. Pevsner is wonderfully snitty about its impact on New England church design. But it is not possible for me to look at Palladio, at Jones, at Burlington, without sensing that their innovation was, and is, something which rapidly became everybody’s, a vernacular which stretched beyond ownership, copyright and exclusivity. This theme would develop over the next few days.

The Cover of Palladio’s ‘Four Books on Architecture’. Kenneth Clark observed Thomas Jefferson’s pride in owning all the copies of the first edition of this in the New World. Without it, Monticello and the University of Virginia, let alone the Declaration of Independence, would not have happened…perhaps

I pulled myself from this jewel-like exhibition, very much of design, not art, but a visual and expressive feast, nonetheless. With a wave at Shelley’s Soho residence, I got myself to the Brewer Street Car Park, a 1920s gem, and currently hosting Bill Viola’s early ‘Talking Drum’. I am not often excited, and almost never impressed, by visual artists messing around with sound, and dare I say it, music. This exhibit, is, however, a considerable exception. There’s almost nothing that I can say, except that I was unable to leave the single space for an hour.

Like so much powerful art, this reminded me of other experiences, of other works. The experiences are personal, but the the work which came to mind, was James Turrell’s ‘Side Look’, which I first saw at the the Lenbach-Haus in Munich in 1992. I was taken to see it by my dear friend, a great photographer, Manu Theobald. Sometimes, we need a guide, to lead us to witness something; she did that, and then, Viola, on Tuesday, send me back over the decades, to that day in Bavaria.

Of course, the experience was far from simple, as on the the train that morning, I had been amusing myself with the beautiful score of Webern’s String Trio Movement, trying to get a sense, of how it worked, how his mind worked, across it’s 24 bars. This attempts found themselves obliterated by the painting (in the dark) which I did, ‘inside’ ‘Talking Drum’. If I am honest, and perhaps I need to be, I was in a state of some shock, even upset. That morning, I found myself holding a letter from Bela Bartok, tipped in to the working copy of the Solo Sonata written for Yehudi Menuhin. It’s dated June 1944.

The last paragraph of the letter shows us Bartok, painfully, aware of his mortality, but also, looking ahead: ‘Let us hope for the future’. I do hope that he had a presentiment of how we see him now, one of the truest voices of any time, one of Bach’s greatest heirs. But that morning, thinking about it, there was more. On the train in from Wapping, the 20 minutes to Baker Street, I had found my way to Tibullus’ ‘Delia’, Book 1 X ‘Against War’

‘Quis fuit, horrendos primos qui protullit enses?/quam ferus et vere ferreus ille fuit?’ (Who was it, who was it that first revealed the dreadful sword?/How fierce and truthfully ironhard was he?’

Once I had finished amusing myself with the ‘ferus/ferreus’ (fierce/ferrous) pun; I realised that ‘Delia’, dedicated, surely ironically, to Tibullus’s mistress, is describing our horrendous times, or so they seem, especially from our safely impotent heights. So Viola provided solace, and then coffee and fruit cake (plus ‘The Continental’, from ‘The Gay Divorcee’) in a cafe around the corner offered relief.

Day 2

On Wednesday afternoon, I found myself waiting outside Barbican Station for a group of art and architecture students fom the RCA, led by my friend and colleague, violinist, anthropologist and fellow-walker, Amy Blier Carruthers. The target was the Champagne Charlie Room at Wilton’s Music hall. I suddenly found myself surrounded by a truly international group, including a fascinating woman from Colombia, who, just having arrived in London, for the first time, seemed charmed by the palimpsest labyrinth of London’s medieval Shambles. And so I led them, off; the north side of St Bartholomew the Great, with memories of the blacksmith’s shop, and a wave to John Betjeman’s london house (‘Love that lay too strong for kissing’, rhyming, wonderfully wMith ‘Where is Wendy? Wendy’s missing? My favourite poem when I was 12, but I never told anyone). Then St Bartholomew the Less (with a wave to Hardwick), and the ‘For the Poor’s [sic]’ box under the arch at the hospital. Postmen’s Park, and the sad stories of GF Watts’s wall, over Aldersgate, past St Anne & St Agnes, to the huge white Coy Carp in the triangular pond by St Lawrence Jewery, and the echo of the Amphitheatre outside Guildhall, and God and Magog and ‘Domine Dirige Nos’. Then back into the alleys to Austin Friars and Pinner’s Passage, and down the Roman way of Bishopsgate to Reuter behind Tite’s Royal Exchange, and back into the alleys, past Simpsons, and St Michael’s Cornhill, and into the glory of Leadenhall Market-dragons, stars and meathooks, and the wonderful dissonance of the Lloyds Building-as Blade Runner as the day it was built. Then over Fenchurch Street, and under the station, through French Ordinary Court, and through the Roman Wall at Minories, and onto Cable Street, and Grace’s Alley, and the wonder that is Wilton’s. Of course, the short walk was surrounded by a great babble of voices from the past: Samuel Cartwright, John Newton, Paganini, Rahere, William Wallace, Rowland Hill, Hawksmoor, Wren, Millais, Raglan, Dickens, John Blow, Henry Purcell, John Walsh, Pepys, husband and Wife, John Evelyn, Sir Isaac Newton…Then I gave the group a moment to grab a drink, before music and conversation upstairs.

At Wilton’s Music Hall-thanks to the team there for organising! 28 10 15 Photos: Malene Sheppard Skaerved

We then talked about music, walking, history, cities and architecture for an hour. I played Biber, Nigel Clarke, Matteis, Torelli, and read Anne Finch. Then I bid farewell to my new friends, and walked the ten minutes home to Wapping-always cutting through the old graveyard of chestnut trees and lampposts straight from Narnia.

Day 3

…to the heart of the matter. SoundBox, at the Royal Academy of Music Museum, focused on some of the astonishing material which is going into the exhibition on Menuhin which I have curated for the Academy. Collaboration is at the hear of this, as Menuhin, who was not a composer or arranger himself, worked with composers for the whole of his career. The materials which are associated with these collaborations raise exciting questions of ownership, of primacy, in the composer-performer exchange: Whose Score is it anyway?

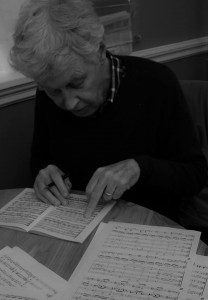

Introducing Bartok’s letter and score to the Audience. SOUNDBOX 29 10 15]

As might be expected, I began with Elgar-the inscribed score ‘E E 1933 -Admiration, Adumbration’, which the composer gave to Menuhin on their last meeting in 1933. But it was earlier that Menuhin’s collaborative work began, when he was just 12, with the beautiful ‘Abodah’, which Ernest Bloch dedicated to him.

A manuscript by Georges Enesco set the tone; his transcription of Paganini’s ‘6th Caprice’, for violin and piano. A few obvious things; this is an arrangement, made for practical use, and it’s clear that it was used-though of course, not by a violinist, who would not need the music of this piece. So it is covered with piano fingerings and instructions – a number of them, in Swedish. The date, ‘1913’ shows that it was not made for Menuhin, who had three years to wait!

I was aware of the mounting excitment in the room, as the astonish treasures spilled out: Menuhin and Ernest Bloch-the first piece carefully annotated by Louis Persinger, through to the working scores of the last-the two Suites for violin (1953), on which Menuhin has written his bold suggestions for rewriting the end of the piece. This question of dramatic endings reemerged with the Frank Martin ‘Polyptyque’; a few years after Martin died, Menuhin and his old friend, conductor Antal Dorati, exchanged letters and scores with a revised ending, using celebratory bells in this work for violin and strings, to increase the mood of ‘glorification’. Immediately the sense of territory was in the room. What can we, should we, shouldn’t we do, to a composer’s work. When a piece has been written for me, how much is it ‘mine’? I am aware that there is no right answer to the question, especially when I reflect on what my job as an interpreter is, or should be.

This question is perhaps unavoidable, handling the materials that went between Bartok and Menuhin in 1994, between the completion of the Solo Sonata in March of that year, and the November premiere. Ththe ere has been plenty of ink spilt over the versions of the sonata which emerged from this. Suffice to say, that it’s very clear that Menuhin put an enormous amount of work into studying the orginal version (this is, without doubt, the most carefully marked, of all of his scores), so it is a challenge, and even an ethical quandary, to decide, especially if you are a performer-where to enter this dialogue. Having spent so much of my life in the ‘composer’s workshop’, I can say that not entering the discussion, is just cowardice. My teachers Ralph Holmes and Louis Krasner, simply won’t allow me to stand aloof.

After the session, there was, as you can imagine an excited huddle of people, astounded at suddenly finding themselves up close and working with MSS from Bartok, Bloch, Elgar, Martin, Berkeley, Enesco. I am still shaking.

But the day was only just getting going. After an hour of letter-writing, I sat down with Daniel-Ben Pienaar for the next stage of work on our Mozart Project. This turned into an evening of wide-eyed wonder at the D Major Sonata K 306. This was written in Paris in the summer of 1778, where Mozart’s mother fell ill, in June, and died. It is generally regarded as an unsuccessful piece, perhaps because of it’s ‘concertante’ nature, just that it’s too Parisian, like the 31st Symphony. However, soon Daniel-Ben and I were wide-eyed with wonder (it does help to be sitting next to one of the great living Mozart pianists). This is one of the great works, and it was almost impossible to tear ourselves from it at the end of the evening.

Friday proved as uplifting as the rest of the week. After a morning with students on the masters course at RAM, I met with Julian Perkins to move forward with our Schubert 1816 project, soon to go into the studio. We spend our hours working on the last of the the keyboard/violin sonatas from that year.

What Julian called the ‘happy aftermath’ of rehearsing Schubert G minor Sonata D408. Broadwood Square Piano 30 10 15

We have become more and more convinced that the 19 year old Schubert is daring us, even taunting us, to go deeper to respect the music more, by teasing with it, as it teases with us. So we are experimenting, with dramatic embellishments, transpositions, internal repeats, colours, revoicings… a conversation about the 4th Estate emerges: ‘They’re going to crucify us’, Julian notes. He’s right, but this is the way Schubert is pointing – whose score is it anyway?

Finishing the rehearsal, I rush down to meet with David Matthews; he has trouble in his hands…the Schumann Piano Quintet…

As you may know, along with David’s extraordinary violin and chamber music, it has been my privilege to work with David on his transcriptions and revisiting of works by Beethoven, Bach, Schumann, Scriabin and more. It is clear that David regards part of his duty as a composer, and ours, as performers, to show respect to the past, by interrogating it. David is fascinated by the issues in this wonderful work (the Quintet), and has ‘had a conversation’ with Schumann, about a number of questions of voicing and colour. The result is the work, subtly, but significantly refocused, and it is fascinating to discuss, with David, the opportunities and ‘danger areas’ of this process. And, extraordinary to find myself in this discussion, just minutes after the extended work with Julian on Schubert.

But the day was far from over. After an hour with David, I raced off to the Tube, with pianist Roderick Chadwick. We were on the hunt for a piano for recording; rumour had come to us of a great instrument in Harrow. So we found our way to the beautiful St George Headstone, on Archbishop Cranmer’s old Harrow estate.

This was nothing but luxury for me. I was shown around this beautifully kept Edwardian building, a treasure house of fine joinery, and a lovely acoustic, while Roderick played Chopin, Messiaen and Jeremy Dale Roberts on what turned out to be a peach of a piano. We have found the venue to record Dale Roberts and the Henze Violin/piano music. A wonderful end for the week. On the way back to West Harrow Station, a Kestrel stooped low over us, and then we were gifted a perfect twilight. As Bartok wrote in his letter to Menuhin, June 1944:

‘Let us hope for the future’

MORE LATER…

Posted on October 30th, 2015 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved