Announcing the Mozart Project-September 5th 2015

After a summer of work on the manuscript of the 5 violin concerti, I am initiating the ‘Mozart Project’, which is routed in the ideas, colours, timbres, well everything which wells up from these amazing works. Beginning this year, I will be leading a series of workshops, leading to concerts and recordings, which will delve into the issues which arise from Mozart’s reworking of the concertante idiom after the return to Salzburg in 1772. Nothing is off the table; I have been talking with my collaborating players and and composers about the inspirations and questions which spring from Mozart’s rejuvenation of the concerto idiom.

The project will not be confined to the UK, but aims to have outcomes on both sides of the Atlantic; there’s so much to explore in these works, and in the roads which lead to and from them, that I want to learn from the widest cross section of players, composers and thinkers.

The Piano Concertos and Piano/Violin Sonatas

A vital aspect of this work will be the work with virtuoso Daniel Ben Pienaar on the piano concertos. This is a long term, dream project, to explore these works in an ideal situation. The project will begin with a cyclical performance of the sonatas leading into in-depth ensemble workshops on the concerti.

Discussing Mozart at Somerset House 11 9 15. Daniel Ben Pienaar with composer-violinist Mihailo Trandafilovski

Note to Daniel Ben Pienaar-13th September 2015: ‘I have started thinking very carefully about Mozart’s technical gambits-as a cast of characters/fixed integers, recurring and developing, within individual pieces and over the arch of long and short term development of ideas. Last night I tried an experiment, and just treated the 5 Violin concerti only in terms of descending broken chords/figuration. Just dividing these into three clascuclees (semi quavers, triplet quavers/duplet quavers), and practising/logging their appearance/disappearances/morphings across the cycle, was eye-opening, and (as I should have expected), pushed me to a more carefully consideration of the interdependence of (rough/artificial separation) decorative figuration/virtuosity and lyrical materials. Also watching Mozart fall and out of love with a gambit (sometimes in the course of a movement, sometimes between three pieces), is amazing.

Thursday October 1st Fingering

I have hesitated before talking about Mozart’s approach to the left hand. My ideas are in flux, at the moment, but begin from a conviction that there might(!) be a relationship between Mozart’s technical approaches to the keyboard and violin (almost approached as one entity), and his compositional decisions. The other consideration, and perhaps the most important one, is the impact of his brilliance, and efficiency, as an improviser, on his technical approach.

I can’t talk about this without mentioned Leopold, and, indeed, there are more than a few occasions in the the concerti, when the young man doffs his violinistic hat, not only to his father, but to the illustrations in the 1756 Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule. There, are, as might be expected many declarations of independence from this school!

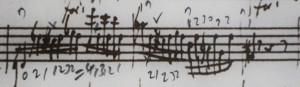

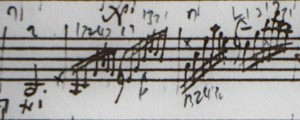

Here are two examples of how Mozart moved the hand around the violin, taken from the B Flat Major ‘Rondeaux’ (spelled thus on the MS), which seems to date from 1775 or thereabouts.

Semitone hand adjustments.

Semitone adjustments. This pattern, in three transpositions, occurs three times on one page in the MS. Of course, it could be executed by an extension from 2nd position, but my hunch, is that Mozart preferred to avoid ‘fanning’ of the left hand, which results, always in a degree of intonation insecurity, particularly in figuration. The pencil marks, are mine, of course, illustrating the possibility discussed. 1 10 15

Moving around the instrument in blocks.

Moving around the instrument by block. This ‘rhythmic fingering’ (as Leopold Auer would call it), means that the same fingering is used for each chord change on the half bar. Very much, an improvisers gambit, it’s a pattern which we can see used all across Mozart’s concertante violin writing in the 1770s (1 10 15)

Monday September 7th- a moment to think about dynamics.

In the 392 pages of score (including the replacement E major Adagio for K216), Mozart marks dynamics 17 times in the solo partThis is not necessarily remarkable. However, when we make the decision of what the relationship between solo and tutti parts should be, in terms of loud and soft, of relief, it is relevant. In all of these locations, it is clear that Mozart has added the dynamics in the solo part as a note that the dramatic effects in the tutti should be matched in the solo part. In only one or two places is the marking confined to the solo – and that is where no one else is playing.

In the majority of cases, as one would expect in a concerto of this period, there are no dynamics in the violin part, but dynamics in the supporting parts. It is very far from clear when these are, for instance, ‘piano’, to avoid drowning the soloist, or as a clue as to what dynamic the solo violin should be playing. In a significant number of locations, there is a ‘new’ dynamic added in the solo line when it rejoins the tutti violins. This might indicate that this is a contrast, an arrival point, or just be there as a reminder.

A small question, just to begin 5th September

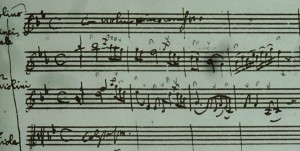

One of the areas which fascinates me is the care with which Mozart negotiates the soloist’s departures and arrivals into cadenza points. This is not something which I seen explored, and I am not yet sure how to use this information. But it fascinates and provokes in equal measure. Here’s an overview, scribbled yesterday, of all five concertos’ significant cadenza points, with the relevant information.

An overview of the ‘arrivals’ and ‘departures’ at the standard candenza points in the 5 concerti, with linking orchestral tessiturae. 4 9 15

Mozart-Five Violin Concertos K 207, 211, 216, 218, 219

This summer-away from the stage and the microphone, I am delving into the wonderful manuscripts of Mozart’s 5 Concertos, written when he returned to Salzburg, between 1772 and 1775. This is leading to a major project which will be announced soon. But for now, process!

My friend and collaborator, composer Michael Alec Rose sums up the fascination of these works:

It’s my inkling that these works are the great tectonic shift of WAM’s life. Something truly unheimlich kicks in here, and it’s hard to pinpoint, except to say–too obviously–that he finds his voice and sings now, fully and unequivocally, with an almost terrifying perfection. These are no longer “Classic” works. They transcend the rubric. They are sui generis (and

don’t I know what that means?). Each concerto investigates every conceivable texture, with utter comprehensiveness, and that is one reason why Beethoven’s is so filled with due anxiety from the very start. And it is why Beethoven’s reaches so hard to achieve its own species of tranquility, in another sphere from Mozart’s altogether. (E mail to PSS 4th August 2015)

This is as good a place as any to begin. The transition from ‘solo’ to ‘tutti’ to cadenza in the first movement of Mozart’s G Major Concerto K 216. Mozart took infinite with the crossing points where the concertante violin finds a route in and out of the orchestra. Much of this is lost, when the soloist does not act as part of the orchestral mass.

Responding to the Scores

I will post my undigested responses to the score, as I work on it. My notes are in scatter pencil notes on the MS at the moment. Please note that all bowings and fingers (which will be in pencil and thus fainter) are mine. The page numbers are from the lovely facsimile of the concerti: ‘Mozart Violin Concerti: A facsimile of the autographs. Edited with an introduction by Gabriel Banat’ (Dover Publications, New York 1986).

P. 1 ‘Con violino primo…’ (K 207 1st Movement)

This instruction appears whenever Mozart requires the soloist to play as part of the tutti. It is also used in other forms (particularly in this concerto) as a shorthand, whenever Mozart duplicates material vertically (2nd violinist doubling 1st violins & violas doubling ‘bassi’).

Another note-there are no ‘Crescendo’ or ‘Diminuendo’ indications in this movement

P.2 Simplified oboes when playing with violin melody(K 207 1st Movement)

This is a simple point. Here, the oboes are doubling the energetic violin line, but doing it with some of the more ornamental material left out. This is an obvious point, and has links to questions of instrument technology. Mozart makes a virtue, an expressive gesture out of the proportional limitations of certain instruments. It’s there in the strings as well. ‘Bassi’ do not play 16th note tremolo, but 8th note. This is, of course, as practical as the above, but sets up various ‘Vitruvian’ relationships (2-4-8-16), which are related to octave displacements and doublings, and to the meaning of pitch (which is not the same thing at all). Additionally, having oboes doubling the violin lineSee p.4 note. [come back to this]

P. 3 rows of staccato in an anacrusis, as ‘ups’(?)(K 207 1st Movement)

I am a little nervous about this; it’s a conclusion that I have come to in years of playing the Mozart chamber music. Mozart, in common with other composers of his time, and string practice of the 18th century, would have been unfamiliar with the aggressive 20th century up-bow staccato. Evern listening to Fritz Kreisler playing ‘Scön Rosmarin’, it is clear that his was a vocal approach (often eschewed by players today, when performing this piece), and is grounded in the operatic practice of the 18th and 19th Century. Spohr would call the more brilliant version of the singing style writing his ‘string of pearls’. When Mozart wants this style, he puts a slur over the notes (as can be seen in the slow movement of K207). However, I cannot call to mind an instance where Mozart uses such an ‘over-slur’ with staccato ‘dots’ to indicate a leaping, energetic, staccato on one bow. This is a very round about way of getting to the point, that this example is a typical instance, in Mozart where it feels (to me) that he is expecting the performer to play with a directional, energetic, series of up-bows.

P.4 Complex relationship between oboes and tutti violins(K 207 1st Movement)

See P.2 note: continuing from here, there are instances where Mozart demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of the relationship between oboe/violin doublings (and simplifications), and the drama of breakaway-heterophony. Off course, for colouristic reasons, a section of violins playing ‘unison’ is always heterophonic. So an oboe and violin is even more disparate. So examples where the 2nd oboe peels away, are a natural continuation…

P.4 Wind silent in solo violin sections (K.207)

This concerto shows signs of its links to the earlier convention in the almost complete silence of the wind in the solo sections. Think about how this might relate to early 18th Century works with pairs of concertante oboes (the Haendel model), and how this appears intermittently in these pieces. See next note:

P.5. Top line in the Oboe(K 207 1st Movement)

On very rare occasions, the tessitura of the first oboe rises above the orchestral and solo mass. By concerto 3 (K.216), Mozart starts to experiment with dramatic interventions (development section,, 1st Movement) from the 1st oboe, imploring the soloist to pick up their new motif.

This page also introduces a very Mozartean trope. The break before the second phrase of the solo exposition self-consciously mirrors the break at the end of the first tutti, before the soloist plays. This returns at the equivalent place in the G Major Concerto K 216. The fourth bar includes a triple stop chord, mid passage, for rhetorical emphasis, very rare in Mozart, but familiar, to me, from Michael Haydn’s concerto in the same key, which Mozart clearly knew.

P.11 Look carefully at how Mozart handles the end of solo passages and the re-integration of the soloist into tutti passages

Mozart carefully tailors the last note of the solo part and then brings the soloist in as a tutti player on the third beat of the bar with V2 and Oboe, adding emphasis to their entry. Two points: this has dramatic function, and Mozart never takes a sui generis approach. This is part of the piece. It may not be immediately apparent, but it is rhetoric, nonetheless.

P.24 Operatic cadenza points

In the performance history of the concerto, these ‘holds’ have been neglected. However, this is where the improvisational challenge of the works is the most clearly vocal, operatic.

P.29 Does the solo play in the tutti before a cadenza? Here, clearly no.

Preparing both the soloist and the audience for the final cadenza, the soloist is not reintegrated before the cadenza, but is given nearly four bars rest-the only time in the whole of this movement. But on-

P.30, the approach to the pre-coda cadenza

-perorates with an anacrusis on B flat, dropping an octave. In this case this means that the cadenza emerges from the Oboe 1 part, an octave and a half above the Violin 1 part.

P.32 Crescendo indications (none in 1st movement)

Mozart uses the written ‘crescendo’ marking. The indication only appears twice more in the movement each time enabling the orchestral mass to overwhelm the soloist at the end of concertante passages.

Pp.32-3 Harmonieband style wind writing

P.34 Slurred staccato (strings of pearls)

See my note to P.3. The fact that this technique appears in the tutti should make it clear that this is not a ‘virtuoso’ technique, but a lyrical one. Its use in thirds between the opposite violin sections, is comparatively rare.

Pp. 34-5 Solo not sharing, or elaborating primary material

The fact that the soloist never plays the first subject of this movement as a concertante line should make it all the more clear that it makes no sense not to play the tutti as Mozart has so clearly and emphatically indicated.

Posted on August 4th, 2015 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved