Schubert begins….

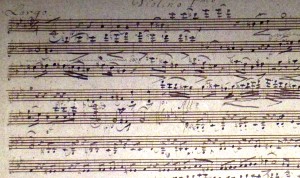

Franz Schubert-Overture D8 (1811) (Original version)

Peter Sheppard Skaerved -Director, Parnassus Ensemble London (recorded 1994)

Franz Schubert-8 Ländler (1816)

Peter Sheppard Skaerved-Workshop Recording. Wapping 21 12 13

Franz Schubert-A Major Rondo D438

Franz Schubert: Konzertstück (for Violin and Orchestra) in D major, D345 – Adagio – Allegro

For Violin with String Orchestra (1816)

Adagio – Allegro Giusto

Peter Sheppard Skaerved-Violin/Director (WE Hill & Sons 1903)

Parnassus Ensemble of London (1993 performance)

Franz Schubert – Fantasie in C major, D.934Peter Sheppard Skaerved-Violin (Guarneri ‘del Gesu’ The Kreisler)/Aaron Shorr-Piano

Schubert-B minor Rondo

Peter Sheppard Skaerved-Violin (Stradivari 1714 ‘Maurin’)

Aaron Shorr-Piano

Live Performance-Svendborg ‘Guldsalen’ 1996

Schubert-String Quintet 1828

Kreutzer Quartet-Peter Sheppard Skaerved, Mihailo Trandafilovski, Morgan Goff, Neil Heyde

Cello-Jessica Hayes

Slow Movement-from live performance Jack Lyons Hall, York, October 21 2009

(NB Audio Rip from video)

Schubert too wrote for silence: half his work

Lay like a frozen Rhine till summer came

And warmed the grass above him. Even so

His music lives now with a mighty youth. [George Eliot]

George Eliot summed up the 19th century bewildered wonderment at the slow release of Schubert’s oeuvre. She was, of course unaware of the work of Ferdinand Schubert or Spina. She would, perhaps, have been a little shocked that figures such as Clara Schumann and Josef Joachim were initially, less than enchanted with all that they heard. There was widespread suspicion that Schubert was turning into a latterday Pergolesi, spawning legion unknown works after his death-many of which would turn out to be bogus. The sheer volume of Schubert’s posthumous works, which, unlike Beethoven, rendered his opii redundant, did nothing to allay these suspicions.

On the 11th of May 1809, Napoleon’s army bombarded Vienna from two days. Schubert, a scholarship student, and the other members of the Imperial Choir boarded in the Stadtkonvikt; during the shelling, the building took a direct hit. The building was directly across the street from the University of Vienna. This shelling, coming two years after the notorious British bombardment of Copenhagen, traumatised Vienna. Beethoven hid in the cellar under the Schwarzspanierhaus.

Schubert’s entire life connected to St Stephens, though never in any official capacity. Whether liturgical or secular, orchestral or chamber, his harmony and melodies never separated themselves from the experience of being a choirboy, and playing the violin later in church services. The Overture begins with a lamentoso (a harmonic progression that reoccurs in all the early works) which has, I feel been purloined directly from the choral works that he would have sung. And indeed, this would have been the sum total of his experience of complex music, as he would not begin his lessons with Kapellmeister Salieri, until a year after this was written. He particularly venerated the religious music of Joseph Haydn’s intermittently brilliant younger brother, Johann Michael Haydn-laying flowers on his tomb in Grosswardein in 1825. Haydn’s liturgical music was an important part of the Viennese choral repertoire, and I like the idea that the long dead Haydn, who had helped Mozart on his return to Salzburg in 1772, in some ways became a composition teacher to the boy Schubert.

At Schubert’s funeral, the music was directed by the choirmaster of St Stephen’s Cathedral, adjacent to the Stadtkonvikt, where he had been a choirboy from 1808-1813. Ironically, it was not his own music that was played, but that of Anselm von Hüttenbrenner, who had been a pupil of Salieri’s when Schubert was studying with him. Hüttenbrenner and Franz sang in a vocal quartet together in the late 18-teens, and, if Schindler is to be believed, visited Beethoven twice together on his death bead, year before Schubert died. One of his fellow choristers, Johann Baptist Wisgrill (B. 1795), became a doctor, and attended Schubert on his deathbed, in November 1828.

Conditions, and food, at the Stadtkonvikt, were far from ideal. In 1812, he wrote to his elder brothers:

“I have long been thinking about my situation, and have concluded that, although it is satisfactory on the whole, it is not beyond some improvement here and there. You know from experience that we all like to eat a roll or a few apples sometimes, the more so if after a middling lunch we have 81/2 hours to wait for a mediocre evening meal.”

Much has been made of the tragedy of Schubert’s early live; that he barely a third of his siblings survived to adulthood, and his mother died in 1812; perhaps the austerity of the regime at the Konvikt was a greater factor.

Every evening at the Seminary, he played in the Seminary orchestra, and became the Kapelldiener-responsible for music stands, instruments and storing the music. He also played chamber music with his family; his two brothers Ignaz and Ferdinand, played the viola, and his father, the cello. It seems that friends and neighbours joined this group, and this became a small orchestra, playing string arrangements of works by Haydn and Mozart, and arrangements of overtures by Kapellmeister Salieri. For some years, this orchestra met in his father’s school room, and the initiative gradually shifted to Franz, and the second oldest brother, Ferdinand, who became a composer of some accomplishment. It would be not stretching a point that Ferdinand’s hand can be seen in some of the writing in Franz’ three works for violin and small orchestra, which were all written for him to play with this group.

The Overture D8 , dated June 29 1811, was Schubert’s earliest chamber work, and being written, it seems, for the extended family group, sits right on the divide between chamber music and orchestral writing. The fact that it is notated for string quintet probably indicates that this was designed to be fitted into readings of transcriptions orchestral works; indeed there were far more transcribed orchestral works for double viola quintet available than there were original pieces. Franz He dedicated the later string quartet version of it to his brother Ferdinand. This however, may actually be a version specifically for string orchestra, and, far from being a reduction, might have been intended for the larger orchestra available to the Schuberts to play. It is very clear, whatever the intention, that Schubert was deeply impressed by the new music that was available him in Vienna; the school orchestra of the Stadtkonvikt, which Schubert lead, had read through pieces by Cherubini, Mehul and Beethoven. The overture also makes direct reference to the completed (1-5) Beethoven Symphonies; indeed these work returned to haunt Schubert constantly throughout his working life; the amazing Trio of the later String Quintet refers directly to the Funeral march of Eroica.

I feel that I have to point out that Schubert’s first and last chamber works for strings are both dramatic quintets for Strings, in C major/minor. This in itself would be worthy of notice, but further than that, they both share a certain quality of mementi mori. T S Eliot noted that:

Webster was much possessed by death,

And saw the skull beneath the skin;

And breastless creatures under ground

Leaned backward with a lipless grin.

This teenage fascination with death is not unusual; after all, plenty of young people react to life with just such mordred fantasies. Here’s a favourite of mine:

“ Today….we are heading south on Highway 101 through Californian redwoods…its 930am, we’ve been on the road since 800 and the children, whom I will call Curly, Larry, Moe, and Marilyn Monroe are plugged into Walkmans, except Marilyn, who is writing a poem “about death”, she told me a moment ago.”

Anyone who has been a teenager can identify with that. I don’t think that Schubert was any different, except that he had more cause to be ‘possessed by death’.

Indeed, the two adjacent D Numbers to the Overture, written simultaneously with it, and sharing much its material, are Eine Leichenfantasie (tr) and Der Fatermoerder (tr).

The Webster-ish obsession persisted, and was perhaps exacerbated by Schubert’s exterior. He noted in his notebook in 1816;

“A light mind accompanies a light heart; yet too light a mind usually conceals too heavy a heart…to be noble and unhappy is to feel the full depths of misfortune and of unhappiness; likes to be noble and happy is to feel both happiness and misfortune to the full.”

Perhaps Schubert’s saving grace was that he belonged to the latter groups, and as his friend Eduard Bauernfeld noted in 1826:

“Schubert has the right blend of the ideal and the real; for him, the world is beautiful.”

Schubert was hoped that Schubert’s love of the outdoors might save him, and in the summer of 1828 he moved to a new house:

“A long house with three rows of nine windows in front, a brown sloping roof and an entry in the middle to a quadrangle behind; A quiet, clean, inoffensive place,…He made the move with eh concurrence of his Doctor Von Rinna, in the hope that, as it was near the country-it was just over the river in the direction of Belvedere-Schubert would be able to reach fresh air and exercise more easily than he could from the heart of the city. George Grove

Indeed, his love of the outdoors persisted till the end. In October 1828, he walked to Eisenstadt (to Haydn’s Grave) with Ferdinand and friends, and two weeks before his death, he walked for three hours. However his behaviour on walking tours revealed much about his nature, ‘too light a mind usually conceals too heavy a heart…’ Another school friend, Franz Eckel, noted:

“on walks…he mostly kept apart, walking pensively along with lowered eyes and with his hands behind his back, playing with his fingers ( as though on the keys), completely lost in his own thoughts.”

In October 1828, Franz Schubert wrote to the published Heinrich Albert Probst:

I am asking myself, when at last the Trio will be published? Maybe you don’t have the Opus number yet? It is Opus No. 100. I await the publication of this with longing. I have already composed three more sonatas for Piano alone, which I with to dedicate to Hummel. Also, I have set yet more Lieder by Heine of Hamburg, which are felt to be out of the ordinary here, and finally a Quintet for 2 Violins, 1 viola and 2 Cellos is ready. I have played the sonatas in various places, with much success; the Quintet however will be tried out for the first time in these days. When these works are of some interest to you, then I will let you know them.

Bibliography

Arnold Schoenberg-Letters, Ed. Erwin Stein, Faber and Faber, London, 1974, Baillot, Levasseur, Catel, and Baudiot, Méthode de Violoncelle, Peters, Leipzig, ?, The History of the Violin, William Sandys, William Reeves, London 1864, Schubert’s Vienna, Ed. Raymond Erickson, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1997, Franz Schubert, a biography, Elizabeth Norman McKay, Oup, Oxford, 1996, Schubert’s Chamber music: before and after Beethoven, Martin Chusid, in The Cambridge Companion to Schubert , Ed. Christopher Gibbs, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997, Whispers of Immortality. TS Eliot, Selected Poems, Faber, London, 1954, Family Honeymoon, from We are Still Married, Garrison Keillor, Viking 1989, March 1826, in Franz Schubert, Music and Belief, Leo Black, Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2003, Schubert, Arthur Hutchings, JM Dent and Sons. London, 1973, Memoirs, Franz Eckel, Schubert-an Heinrich Albert Probst, Wien den 2.Oct. 1828.

Posted on January 19th, 2014 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved