In 2004 I spent some time working on Hans Christian Andersen’s albums in the Kongelige Bibliothek, Copenhagen. By any stretch of

the imagination, these are incredible. I copied out musical entries from Mendelssohn, Spohr, Weyse, Schumann, Ernst, Lachner and this poem, addressed to his ‘Friend and brother poet’ by Ole Bull in 1838.

Andersen and Ole clearly regarded each other as kindred spirits from their first meeting, although Andersen disapproved of Bull’s gambling

Ole Bull in Hans Christian Andersen’s Billedbog

(Kongelige Bibliothek-Copenhagen)

This entry, listed as Stambogsblad , appears on Pge 167 of Andersen’s Album I-IV , and dates from 1838

‘Ole Bull.

Hvad er vel livet uden Krig, et stille staaender

Kjær hvor Alt fordærves, hvad er

Kraft uden Modstand, et intetsigende Ord. Ruste

Krig! Du livets Soel [sic], staae Dine

Sønner bi, bevær Dem længe fra Rust.

Sin Ven og Brøder Digter

A. fra hans

Ole’

I must go out in the world, to bring my spark to a flame

Hans Christian Andersen’s acquaintance with Ole Bull is an intriguing one. I find it fascinating because the two had so much in common. But perhaps the aspect of both their lives which they shared the most, is that, which posthumously has been silenced, to the detriment of both of their legacies. This is their international outlook. I don’t think that it is stretching a point, to suggest that the importance of both men to their respective nations, as examplars or, if you like, gatherers of nationalist identity, made it inevitable, that their respective outputs, would be ‘pruned’ in order to accommodate the schackles of their roles.

On December 8th 1838, Andersen wrote to Bull:

COPENHAGEN, December 8, 1838:MY DEAR GOOD FRIEND,—At this moment you are in my birthplace! I must bid you welcome there, and once more chat with you. It is only some days since we first met, but there are natures that need no longer time to become dear to each other, and ours, I think, are of them./Thanks for the lyric strains of your violin,—if they could be rendered in words we should have a wonderful cycle of poems. Although you played to the world at large, and many felt deeply what a human heart spoke to them in melody, I was egotistic enough—or perhaps you will give my feeling a nobler name—to imagine and dream that it was singing for me alone; that I alone heard you tell in fragments the story of your artist life through your tones! Ah! long before I heard you, I had felt an interest in your genial personality; but now that we have met face to face, seen and understood each other, that sentiment has become friendship. I feel it will be a pleasure to know that you have won a soul; therefore I tell you, and am not ashamed. Every–day people would not understand me, and they would smile at this epistle, but I do not write to them in this strain—only to the friend Ole Bull./One of these days I shall call on your uncle to see the dear little Ole kiss him, and think of his father and mother. The poor bonne, so suddenly dropped down in this corner of Europe, must be lonely. I send your lovely wife a whole bouquet of compliments. She cannot have forgotten me altogether—because of my wretched French, if for no other reason. Yesterday I dined with Thorwaldsen. We spoke of you, and when I told him that I should write to you, he asked to be remembered. He had tried to find you at the Hotel d’Angleterre, but they told him incorrectly, it seems, that you had gone to Roskilde, and he did not succeed in seeing you./What an agreeable surprise would a few lines be from you! Ah, do let me know how your own bodily self is thriving. You were not well when we said good–by—write of yourself. But do so at once, while the feeling is warm; later—well, I fear that if you do not, others will absorb your time, and that you will not write. Send at least a few words—and now, God bless you! May you have all the success and happiness you deserve! Your name has a pleasant sound in Europe, your heart is known to your friends. I have many greetings for you from the C.’s, where I make my home. The spirituelledaughters think a great deal of you; they said they hardly knew you well enough to ask to be remembered, but why should I not tell you what must always be dear to you? Much, much love to you. Farewell! with fraternal heart. Yours,H. C. ANDERSEN.

The first mention of Ole Bull in Andersen’s diaries appears in June 1841, in Vienna:

“Saturday 19th: Very afflicted [Andersen’s diary entries often begin with a reference to his health-often to toothache]. Went straight out to Dikdrikstein’s Palais and said farewell to Thalberg; he was in morning-dress-we gossiped for over an hour together; he promised to come to see me in Copenhagen, maybe next winter; we talked at length about Ole Bull and Liszt. Went to see Bauernfeldt [Bauernfeld], but didn’t find him. Felt more and more sick….”

May 1842, in Copenhagen:

“Sunday 28th: “…met Ole Bull and sat with him in the Theatre for Den Stumme (Auber’s opera La Muette de Portici) where he told me about his newest works – a Tarentella and the Nøkk.”

Ole Bull-Fanitulla (His transcription today housed in the Univeristetsbibliothek, Oslo) Peter Sheppard Skaerved-Violin (Workshop Recording, London August 29th 2012)

On the 24th of April, 1834, Ole Bull stood in for ‘la Malibran’ and Charles-Auguste de Bériot at a concert at the Società del Casino in Bologna. The version that he and Andersen concocted, (see below) is very romanticised. However it is right on one point-this was an event which Bull would always regard as his breakthrough.

- H C Andersen, who met Bull many times, but disapproved of his gambling

An Episode from the Life of Ole Bull-H.C.Andersen (Samlede Skrifter, Sjette Bind, 1877 Pp 125-128)

(translated by Peter Sheppard Skærved)

Told after the artist’s own account.

Beyond the Alps lies the Miraculous Land, the world of Adventures; we would not believe in Miracles, not hear of them. The Tale is dearer to us, of those we would rather hear tell, so it is with this tale, which could only happen to Genius, took place in Bologna, in the year 1834.

The poor Norseman, Ole Bull, of whom nobody knew, had come a long way south. In his home he had well believed, that something stirred in him, but most of all, as often happens, he felt that no one believed in him. He said to himself: I must go out in the world, to bring my spark to a flame …. and so he came at last to Bologna, but here his money was exhausted, and he had no place had h prospect of going anywhere from, no Friend, no countryman reached out a hand to him, alone he sat up in a poor attic in one of the alleyways. It was already the second day, that he had had not a morsel; his water bottle and violin were the only things, that might refresh the young , passionate artist. In despair he was ready to give himself up to God, and he involuntarily struck sounds from the violin, those tones which now so wondrously entrance our hearts, revealing to us how deeply he has suffered and endured.

On that very evening there was a concert at the Grand Theatre; the hall was almost overflowing, the Duke of Toscana was present in the Royal Box, and Madam Malibran and M. Beriot were due to add to the programme with a couple of numbers. The performance was due to begin, but everything was in anxious upheaval. M. Beriot had been injured and not able to play. All was uproar in the Theatre. Then Rossini’s wife arrived, and in that moment of crisis, remarked, that earlier that same evening, walking through the alleys, suddenly she was struck by enchanting sounds from an instrument, which might have been a violin, but which struck her as having a unique quality. She had asked the landlord of the house, who it was living up there the rafters, where the music was coming from. He answered, that it was a young man from the North, and that the instrument was a lyre: that did not satisfy her, and she did not believe it, thinking that, maybe, it was a new percussion instrument, or an artist, that had discovered a novel manner of playing the violin. You should send a summons to him, she said, and perhaps he might be able to replace M.Beriot’s missing numbers.

So with all in crisis, they took her advice and sent a messenger to the little street, where Bull sat in his attic room. For him, it was like a sign from Heaven; it’s Now or Never, he thought, and despite being sick and weak, he took his violin under his arm and went to the theatre.

Two minutes later the director announced to the assembled public that a young man from the North,, or rather ‘a young wild man’ would be heard playing the violin in Beriot’s place.

Ole Bull stepped forward; the theatre was blindingly lit up. He say the nearest women’s curious gaze; One of them, who had examined him the most closely, whispered, grinning to her neighbour, a sarcastic remark about the artist’s timid manner. The neighbour noticed Bull’s thin clothes – in the strong lighting his extreme poverty really stuck out. The woman noticed all of this – her smile gave Bull new heart.

He brought no music with him, that he might have given to the orchestra, so he had to play without accompaniment – but what should he play? “I would like to offer you a phantasy, play it in the very moment that it strikes me!” and, improvising, he offered them the memories of his own life, melodies from his homeland’s mountains, has struggle with the world, and his whole soul’s agitation; it was, everyone thought, as if his every impulse flooded through his violin, and thus opened him up to the multitude. The most tumultuous chorus of acclaim ran through the room. Bull was called again and again, eight times. They demanded that he play another piece, a new improvisation.

He went over to the very lady, whose sarcastic smile had greeted him upon his entry, and requested that she offer a theme to varier. She gave him one from Norma. He went then to two other ladies, and each of these gave him one, from Otello, and one from Moses.

“What if I take all three themes” thought Bull , “ let flutter around each other, then lead them into one musical piece, so will I flatter each of the women and maybe with the composition, make a great effect.”

So he thought, so he did. He played: magically, like the Magicians wand, his bow glided over the strings, in the midst, freezing fountains burst on his troupe; there was a fever in his blood, it was, as if he loosed wild prophecies. Flames blazed in his eyes, he felt himself trembling with nerves, sink down; at last, with a couple of giant bow strokes, he exhausted last of his playing strength. Flowers and garlands fluttered around him in torrents, and exhausted by the torment of his soul and hunger, he fainted in a fit of vapours.

Then he went back to his home, this true knight with music. Outside his house Serenades were played for the hero of the evening, meanwhile he snuck up the narrow, dark staircase, higher and higher, into the poor attic room, where he grabbed his water bottle, to refresh himself. That was a Tale from our time, a Tale that only Genius could live.

When everything was still again, the landlord came up to him, bringing him food and drink, offering him a better room. The very next morning he was informed, that the Theatre was at his service, and that a concert was to be arranged for him. An invitation from the Duke of Toscana followed, and from that moment, the name and reputation of Ole Bull established.’

The story as related to Sarah C. Bull

Bull told a slightly different version of the story to his second wife, Sarah, as she recounted in her 1883 Ole Bull-A Memoir (Boston-Houghton Mifflin and Company, Pp.55-60):

‘Bologna was, at that time, reputed the most musical city in Italy; and its Philharmonic Society, under the direction of the Marquis Zampieri, was recognized as one of the greatest authorities in the musical world. Madame Malibran had been engaged by the directors of the theatre for a series of nights; but she had made a condition which compelled them to give the use of the theatre without charge to De Beriot, with whom she was to appear in two concerts. Zampieri seized the opportunity of persuading these artists to appear in a Philharmonic concert. All was arranged and announced, when, by chance, Malibran heard that De Beriot was to receive in recognition of his services a smaller sum than had been stipulated for herself. Piqued at this, she sent word that she could not appear on account of indisposition, and De Beriot himself declared that he was suffering from a sprained thumb.

Ole Bull had now been a fortnight in Bologna. He occupied an upper room in a poor hotel, a sort of soldiers’ barracks, where he had been obliged to take temporary refuge, because of the neglect of a friend to send him a money–order. Secluded from society, he spent the days in writing on his concerto; and when evening came, and the wonderful tones of his violin sounded from the open windows, the people would assemble in the street below to listen. One evening the celebrated Colbran (Rossini’s first wife, and a native of Bologna) was passing Casa Soldati and heard those strains. She paused. The sounds seemed to come from an instrument she had never heard before. “It must be a violin,” she said, “but a divine one, which will be a substitute for De Beriot and Malibran. I must go and tell Zampieri.”

On the night of the concert, Ole Bull, having retired very early on account of weariness, had already been in bed two hours, when he was roused by a rap on the door, and the exclamation, “Cospetto di Bacco! What stairs!” It was Zampieri, the most eminent musician of the Italian nobility, a man known from Mont Cenis to Cape Spartivento. He asks Ole Bull to improvise for him; and then cries, “Malibran may now have her headaches!” He must off to the theatre at once with the young artist. There is no time even for change of dress, and the violinist is hurried before a disappointed but most distinguished audience. The Grand Duke of Tuscany was there, and De Beriot with his hand in a sling. It seemed to Ole Bull that he had been transported by magic, and at first that he could not meet the cold, critical exactions of the people before him; for he knew his appearance was against him, and his weariness had almost unnerved him. He chose his own composition, and the very desperation of the moment, which compelled him to shut his eyes and forget his surroundings, made him play with an abandon, an ecstasy of feeling, which charmed and captivated his audience. As the curtain fell and he almost swooned from exhaustion, the house shook with reiterated applause.

When, after taking food and wine, he appeared with renewed strength and courage, he asked three ladies, whose cold, critical manner had chilled him on his first entrance, for themes to improvise upon. The wife of Prince Poniatowsky gave him one from “Norma,” and the ladies at her side, one each from the “Siege of Corinth” and “Romeo and Juliet.” His improvisation, in which it occurred to him to unite all these melodies, renewed the excitement. The final piece was to be a violin solo. The director was doubtful of Ole Bull’s strength, but he stepped forth firmly, saying, “I will play! oh, you must let me play!” and again the same unrestrained enthusiasm followed. When he finished there was a rain of flowers, and he was congratulated by Zampieri, De Beriot, and the principal musicians present. He was at once engaged for the following concert, and the assistance of the society was offered for a concert of his own. One gentleman asked for sixty tickets, another for one hundred, and Emile Loup, the owner of a large theatre in Bologna, offered him his house and orchestra free of expense.

The wheel of fortune was turning in his favor; the Norns were now weaving bright threads in the web of his life. He played at both concerts, was accompanied to his hotel by a torch–light procession, made honorary member of the Philharmonic Society, and his carriage drawn home by the populace. This was Ole Bull’s real début.

Malibran was at first angry, and would neither see nor hear him. He had superseded the man she loved, and she possibly suspected some intrigue. At last she allowed him to be introduced, and civilly asked him to play something. After the first tones the blood rushed to her face, and when he had finished she exclaimed: “Signor Ole Bull, it is indeed your own fault that I did not treat you as you deserved. A man like you should step forth with head erect in the full light of day, that we may recognize his noble blood.” From that time she had for him not only a friendly but an affectionate interest. Another day when he was playing at her house, she said: “He has a much sweeter tone than you, De Beriot.” The latter thought that the superiority lay in the instrument, but failed on trial to satisfy her of this.

One night at the opera Ole Bull, who was standing at the side of the stage, was so completely overcome by the dramatic power and the glorious voice of the great artist, that, unconsciously to himself, the tears were streaming down his face. Suddenly Malibran caught sight of him, turned for a moment from the audience, and without interruption perceptible to them made a most absurd grimace. The discovery of her entire self–control while she moved others to the utmost was a disappointment which he could not afterward disguise, but she laughingly excused it by saying: “It would not do for both of us to blubber;” and when he thought what a comic sight his face must have been he could not help joining in the laugh.’

Ole Bull-Halling til Studenternes Selskab den 10de December 1848Workshop recording, London 31st August 2012 Peter Sheppard Skaerved

The Halling for the Students-MS. NB-I used an appropriate Hardanger ‘scordatura’ with the lowest string tuned up to A

Ole Bull-Fanitulla (His transcription today housed in the Univeristetsbibliothek, Oslo) Peter Sheppard Skaerved-Violin (Workshop Recording, London August 29th 2012)

From the 28th to 30th March 1849, there was a series of tableaux at Christiana (Oslo) Theatre. One of these represented Jorgen Moes’ poem Fanitullen which Bull accompanied with his version of the ‘slått’ of the same name. A manuscript of a later version that Bull played of this Hardanger tune is preserved in the University Library, and that is what I have recorded here.

This is the first verse of Møe’s poem on the ‘slått’, ‘Fanitullen’, which was banned intermittently in the 1700’s as it tended to encourage violent brawling-‘I hine hårde dager/da ved øldrikk og svir/hallingdølens knivblad/satt løst i hans slir, -/da kvinnene til gilde bar likskjorten med, /hvori de kunne legge /sin husbonde ned…’

Link to more Hardanger Transcriptions

Ole Bull – Halling & Springdands (sic)reg Bergen Offentliche Biblitek (Bull 260833)Workshop recording Amsterdam 18th August 20012 (hence tram bell!)Peter Sheppard Skaerved-Violin

Arkansas-the-way-it-wouldnt-doArkansas-the-way-it-would-do

Maud Powell Remembers Bull

I would like to think that Ole Bull would have enjoyed some of the dramatic and colouristic gambits beloved of composers such as Nigel Clarke, Helmut Lachenmann and Volodmyr Runchak. The first great truly American violinist, Maud Powell (a pupil of Joachim’s), remembered one of these:

‘The old days of virtuoso tricks have passed-I should like to hope for ever. Not that some of the old type virtuosos were not fine players. Remenyi played beautiful. So did Ole Bull. I remember one favourite trick of the latter’s, for instance which would hardly pass muster today. I have seen him drawn out a long pp, the audience listening breathlessly, while he drew his bow way beyond the string and then looked innocently at the point of the bow as though wondering where the tone had vanished. It invariably brought down the house.’ (Maud Powell-Karen Shaffer & Neca Greenwood, Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa 1988, P.65)

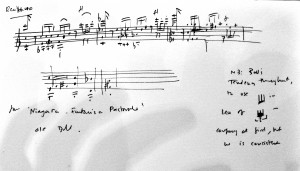

A Fragment of the unfinished ‘Niagara-Fantasia Pastorale’

Ole Bull-Recitative from ‘Niagara’ (workshop recording-Peter Sheppard Skaerved. 2012)

My transcriptionof the fragmentary violin part of the lost ‘Fantasia Pastorale-Niagara’, which Bull composed after visiting the Falls in 1845. This Manuscript hints at a dramatically new, impressionistic approach to orchestral colouration, particularly the opening, which appears to represent the mist and rainbow effects one sees. This ‘Rectative’ is one of only three sections of violin solo writing which are to be found in the ms. Like Paganini, Bull had a tendency, I feel to build his solo material in a quasi-improvisatory manner in fixed orchestral, piano, or mixed keyboard frames.

Posted on October 16th, 2012 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved