A resource Page – Autumn 2020

Insights from Beethoven’s MSS? [in preparation ]

In all of my writing about Beethoven, I realise, that I have never included the thing which I have talked about the most, which is, of course, how much we players can ‘get’ in the broadest sense, from his working materials. I don’t mind saying, that, as far as I am concerned, there is no right nor wrong way to learn from a manuscript. In my case, my excitement ranges all the way from the pragmatic (what the material tells me) to the imaginative (how the access to the composer, at work, inspires me). It is the job of the artist to be both these things, and everything between, and there’s nothing better to explore this, than the astonishing manuscripts for the three sonatas for piano and violin Op 30.

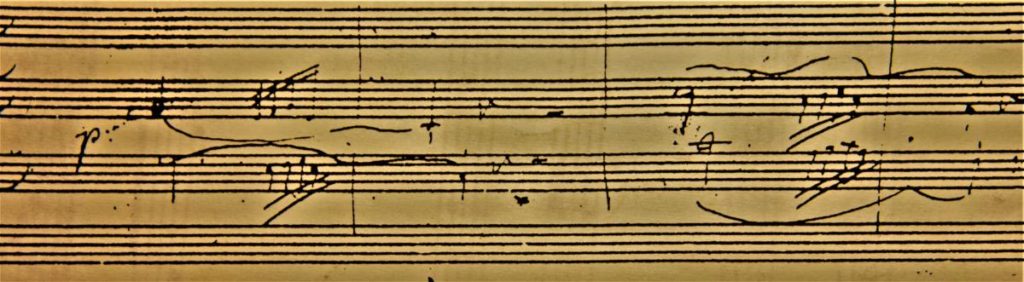

This material will grow over the next week or so, but the first idea I would like to share is something in which I believe passionately, that the composer with their pen, just like the artist, is unable to prevent involvement with their work revealing itself in the notation of that material on the page. That is not as trite as it sounds. Here’s why not: there is distance, correlation and sometimes, contradiction, between the conception, the design, the intention of a visually expressed work of art, be it score, or drawing. What do I mean? Put simply – the stroke of the pen on the paper, whatever it represents by way of intention, of design, also reveals, intentionally or not, the ‘state’ of the artist, in the moment or moments that they executed it.

Forgive, me, if I digress to early 20th century expressionist art to make my point. This a detail from a typically fraught self portrait, by the astonishing, and often shocking Egon Schiele (1890-1918). The useful thing about this, is that we take it ‘as read’ that, the very essence of Schiele’s astonishing technique, is that there would be no way, that the fury of his internal existence, would not express itself in the stroke of the pencil on paper. We can see other versions of this in the work of Gabriele Münter (1877– 1962), or Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945). In our own time, the astonishing technique of David Hockney reveals something similar – what T S Eliot called ‘the circulation of the lymph’.

It’s pretty clear to me, that to a greater or lesser degree, we can witness the same thing in the ‘composer’s hand’. In the case of Beethoven, I have to say, that I think that we can witness a profound manifestation of this. At its simplest, this means, that at any given time, the ‘look’ of the music on the page, will reveal the composer’s involuntary response the the music. I would suggest that this is sometimes exaggerated, or manifested more, when, like LvB, the composer is the player. So, if you take the opening of the C minor Op 30 No 2 sonata -which begins with these octaves in the piano, it’s pretry clear that the ‘shimmy’ on the slurs drawn over each six-note motif reflects the composer’s experience or imagination, of what he expects us to do, what he expects to do at the the piano.

So there’s a question that needs to be asked. Knowing this, what is my, our, your, reaction? Should we respond as if we were working with a graphic score? (and of course, we have to ask the question – was Beethoven doing this intentionally?)

One of the most exciting aspects of Beethoven’s sonatas for piano with violin, is that they are dynamic documents of collaboration at work. The MSS for the first set group (Op 12) are missing, but the surving materials for Op 23/24, and Op 30 (1-3), reveal aspects of Beethoven’s extraordinary work with the violinst Ignaz von Schuppanzigh. The remainder (Op 47 & 96) reveal his work with George August Polgreen Bridgetower and Pierre Rode respectively. An often overlooked aspect of this is that these working scores had to be playable by both musicians. The first sonata where we know that Beethoven made a separate (copied) violin part was Op 96, for Rode. Consequently these scores tend to be neater than was usual when Beethogven was writing just for himself (when the scores had more of a mnemonic quality), as Schuppanzigh had to be able to read. This yields real benefits and insights for us. TBC

Practice thoughts. September 2020 – A wonderful introduction

(30th September 2020) Tonight, I am back at the practice desk with Beethoven’s wonderful G Major Sonata Op 30 No 3. I am playing the set of three in York in November with Roderick Chadwick, and we have been stealthily exploring them over the summer. I think that it’s fair to say, that there is no Sonata which I know better, but it strikes me, as I sit here with my violin, the score, and a facsimile of the manuscript, that I am as fascinated, and enchanted with this piece as the very first time that I worked on it, when I was 14. Since then, I have performed this work many times, and recorded it with Aaron Shorr, who was my regular duo partner for about 20 years.

I think that this was the piece that made me fall in love with Beethoven, and I think that the reason was that I was introduced to this piece by my teacher, the great British violinist, Ralph Holmes. I have written a lot about how much I owe Ralph, but not much about how he taught Beethoven.

This sonata was far from being the first Beethoven I had studied. Like every young violinist, I played the Op 24 ‘Spring’ Sonata. But it seemed to me then, and it seems to be now, that something happened in those lessons on this piece with Holmes. And perhaps it behooves me to say a little about it, as I end my work for the night.

I was never really sure why it was that Holmes had taken me as a student two years earlier. I was technically behind, and musically ill-educated, and ill-informed. When I asked him, about a year before he died (in 1984, when I was 17), he said that there was something in my eyes, that said, that I would not be denied the violin. In that, I think he was right.

But when we started working on the G Major Beethoven, my lessons changed, and it seemed as if the teacher-pupil dynamic shifted. He worked on my exploration of this piece, as if he was preparing it himself – which was partially true, as it was one of the 10 Piano/violin sonatas that he performed the most. Tragically, he never had the opportunity to record the cycle, which I regard as a huge loss to violin playing.

But in these lessons, Ralph confronted me with the seemingly impossible demands Beethoven makes on us, as players, which are nothing to do with right notes, and everything to do with honesty, and uncompromising delivery of the expressive markings, the shape and colours which are the essence of a score like this. The most obvious of these as the crescendo-crescendo SUBITO PIANO, which Beethoven uses more in this Sonata than in practically any other work. At that time, Ralph was playing mostly with the pianist Geoffrey Pratley, and he came into so many of my lessons and played with me, except when Ralph pushed me away from the stand (which was a lot): the greatest strength of his teaching was that he taught by doing (not showing, which is different). And these sessions infected me with the excitement of meeting Beethoven’s demands, finding the life in every note, ever gesture.

Within a year, he had me playing the Concerto, and at the same time I began playing Quartets seriously for the first time, with Hilaryjane Parker, who was a couple of years older than me, and far ahead in her understanding of chamber music. The first quartet we played together was the Op 95 …

Every time I come back to these pieces, I realise how lucky I was to have this demanding introduction to these works. My gratitude to Ralph is lifelong, and Beethoven is the life blood of what I do as a musician, anniversary or no. I can’t wait for the rehearsal in a few hours’ time.

Beethoven – 3 Sonatas, for Piano and Violin, Op. 30

(Dedicated to Tsar Alexander 1st)

Beethoven dedicated his three Sonatas for Piano with Violin, Op. 30, to the Tsar Alexander 1st (1777-1825). In 1800, Alexander took the throne after the murder of his father, the Tsar Paul; it was widely assumed that he was behind the assassination. Upon his accession, he led a bloodthirsty campaign to the Caucasus, which resulted in the death of 25,000 Circassians. Nonetheless, he was perceived as a true child of the Enlightenment; he had been educated by his grandmother Catherine the Great, who put him in the charge of a radical Swiss tutor, who was a disciple of Rousseau. This in itself was not necessarily a badge of strictly liberal credentials, as Marie Antoinette herself had been a loyal adherent of the cult of the author of the ‘Social Contract’, and frequently made pilgrimage to his tomb. Alexander introduced many reforms in the early part of this reign, most particularly instigating governmental, legal and educational reforms. In 1793, he had married a German, the Princess Marie Luise August von Baden (1779-1826). Upon joining the Russian Orthodox Church in order to marry, she had taken the new Christian names Elisabeth Alexievna.

The new Tsar was lionized in Vienna, and in 1802, always quick to seize the opportunity to make a political advantage; Beethoven requested permission to dedicate the three new Sonatas to him. Alexander supposedly sent a diamond ring in appreciation, and in advance of the promised commission. However, the Tsar left Vienna without paying Beethoven for the works, which debt still remained unpaid when he returned for the Vienna Congress in 1814, where he met Beethoven again.

Beethoven sought to resolve this through a ruse, devised by Dr Andreas Bertolini, his medical adviser from 1806 to 1816. Bertolini hatched an elaborate plan which involved obtaining permission to dedicate a Polonaise for piano, to the German Tsarina, who was an ardent fan of this new dance fad. When Bertolini first suggested the plan to Beethoven, the composer demurred, saying that he had no wish or inclination to write Polonaises, and that he especially disliked writing music to order. Bertolini persisted, and suggested that Beethoven should sit at the piano and improvise dance tunes, until Bertolini heard one which would suit. This was duly done, and Beethoven wrote out the resulting Polonaise Op 89. With help from Count Pyotr Wolkonsky, one of the imperial household ministers, Beethoven and Bertolini gained an audience to present the new piece. Exactly as planned, he successfully exploited the German empress’s embarrassment at the 12-year old outstanding fee, extracting 100 Ducats for the three sonatas, and 50 more, for the piano piece. It is of course, worth noting, that it was not entirely surprising that the outstanding fee for the sonatas had slipped Alexander’s mind; after all, a war, including the Battle of Borodino and the burning of Moscow, had intervened. Alexander later became obsessively religious, and was one of the ten subscribers to the Missa Solemnis.

The three manuscripts of the Sonatas, Op. 30 are among the most expressive of the surviving original material of Beethoven’s chamber music. They also offer a unique insight into Beethoven’s working methods, particularly into his collaboration with the violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh (1776-1830).

Schuppanzigh had been Beethoven’s violin teacher, from 1794, a replacement for Ferdinand Ries’ father, Franz, his teacher in Bonn. A memo written that year reveals that he was taking three lessons a week, along with his technical studies with Johann Albrechtsberger and Anton Salieri. Information is sketchy at best, but is seems clear that their regular lessons gradually morphed into consultations on string techniques and eventually into what, for better or worse, can best be described as workshops. As ever, Beethoven’s correspondence is unhelpful on this subject. He did not habitually write to the people that he saw very regularly.

An example of this was the Czech composer and flutist Anton Reicha (1770-1836), his exact contemporary. Reicha was his colleague in the Bonn court orchestra, and then was in Vienna for eight years from 1802. There is evidence of a deep collaboration between the two, of mutual development of ideas, but practically no surviving correspondence. Nor would there needs be, for as a rule, the closer artists collaborate, the more frequently they work together, the less documentation there will be of that collaboration. Their communication takes place face to face, over the dining table, or in the rehearsal room.

And so it is with Ignaz Schuppanzigh (the dedicatee of the first three Sonatas for Piano and Violin, Op. 12. Schuppanzigh had been pupil of Anton Wranitsky. In the mid-1790’s he had become leader of the Prince Lichnowsky’s private quartet. Wranitsky’s other pupil, Josef Mayseder, who Beethoven called, ‘the Genius Boy’, became the most successful composers of Polonaises in Vienna, and the second violin of Schuppanzigh’s quartet.

Ignaz von Mosel wrote:

“Schuppanzigh, who understood so perfectly how to interpret Haydn’s and Mozart’s ideas, was perhaps even more qualified to perform Beethoven’s compositions, The inspired composer soon realised this and chose him has his favourite interpreter. No sooner had his creativeness given forth, no sooner was the music copied, than Beethoven would give him his works to perform, first in the house of the music-loving Prince Lichnowsky, then later at von Zmeskall’s, the Royal Hungarian Court Secretary, a universally admired art connoisseur, and Beethoven’s trusted friend, who gave the most interesting concerts, to which the elite of the art work thronged.”

Beethoven’s abuse of Schuppanzigh over his obesity, and later, over his problems performing the final quartets, is well-documented. It tends to overshadow the evident depth and subtlety of their collaboration. The Op. 30 manuscripts provide elegant clues as two their rehearsal and workshop processes. The two met when Beethoven moved into Alserstrasse 45, the building owned by Prince Lichnowsky. The Prince ran Friday morning chamber concerts, where from 1794, Schuppanzigh’s group regularly played. From 1795, the responsibility for the string quartet mornings was shared with Count Rasoumovsky.

It is clear from the three Manuscripts, that Beethoven brought the completed score to work through with Schuppanzigh. At this point, the MS was clean, a Rheinschrift. But the scores provide evidence of at least three separate processes at work in those rehearsals. These are the processes which any musician who has collaborated with a living composer will recognise. The first is structural alteration. Beethoven was a structural perfectionist, but also a pragmatic performer. The upshot of this was that he was on occasion willing to break the structural integrity of a work in order to render it more impressive, more effective. In the Scherzo movement of the second sonata, the C minor, the manuscript incorporates a pasted-in addition. That is to say that Beethoven finished the movement, and brought it to Schuppanzigh. However, when they played it through, the passage did not seem effective, and so Beethoven, provided a patch, a few more bars, to emphasise his musical point. This is the kind of process that often happens when a composer hears their music for the first time; a practical musician such as Beethoven would be keen to spot such aural weaknesses, and maybe through joint improvisation, come up with an improvement.

Wegeler describes this process, with Beethoven working on his Op. 1 Piano trios with Schuppanzigh and Anton Kraft, Haydn’s great collaborator, and at that point the cellist of the Schuppanzigh quartet:”

“Kraft pointed out for him that he should mark a passage in the third trio with sulla corda G , and that in the score of the this trio, the finale, which Beethoven had marked 4/4, should be changed to 2/4″

The second result of the collaborative result is most clearly evident in the exquisite manuscript of the G major Sonata, Op. 30 No 3. Of all the three manuscripts for the Op. 30 sonatas, this is one where the neatness of Beethoven’s handwriting, or otherwise, betrays most of all the places where intervention has taken place at the rehearsal stage.

It is worth pointing out, that it seems clear that Beethoven was not in the habit of making separate copies of the violin parts for Schuppanzigh to play from. It seems that their normal practice was most that the violinist would play looking over Beethoven’s shoulder at the manuscript score on the piano music desk. The modern conceit of printing a piano score of a sonata or chamber music with the string part in fainter type, as a cue or mnemonic for the pianist, was still some way off, as when these and similar works were published, it was never in full score, but in separate ‘part books’.

It is particularly clear from the opening of the G major sonata Op. 30 no 3 that dramatic changes have been made to the dynamics of the movement. Large, messy inkblots obscure the barely visible original ‘f’, the original dynamic given to the whirling motif of the opening. This was the obvious volume at which a movement like this should begin, particularly, notated, as it is in unison triple octaves. However, one imagines the two musicians trying it out, and then one of them, whether Beethoven or Schuppanzigh, it matters not, blurting out, ‘but what if it was piano’. From a performer’s point of view, this is a vital piece of information. Knowing that this opening is not a ‘pure’ ‘piano’, but in point of fact, a suppressed ‘forte’, lends it a completely different tenor.

The notion of a ‘suppressed’ dynamic brings us to a third piece of evidence of collaboration which these scores afford. The Variation movement of the first and subtlest of the set, in A major, Op. 30 no 1, includes some triple and quadruple stops, which are notorious amongst violinists for their awkwardness. The difficulty arises from the fact that in the score these chords are marked to be played ‘piano’. At no other point in Beethoven’s output for violin does he mark stressed three and four note chords so quiet; they are distinctly uncomfortable to play. The manuscript reveals what might have been suspected all along, that this variation was more traditional, balancing ‘forte’ violin chords with the piano’s soft and rather chorale-like response, played as one would expect, quietly. This point, does call to mind the joshing relationship that Beethoven had with Schuppanzigh, whom he and his friends were accustomed to taunt as ‘Sir Falstaff’, and to whom he later, famously said: ‘What care I for you and your damned fiddle when the spirit moves me.’ One might speculate that Schuppanzigh seized on the opportunity of these grand chords, as originally written, with great virtuosity, perhaps eliciting an oath from the composer at the piano. This might explain the somewhat frantic scratching out that is visible on the autograph, and the overwritten ‘piano’, simply to spoil ‘Falstaff’s’ fun. This change introduces introduce a novel feeling of delicate bulk to the hitherto sui generis chords. It is worth noting that Beethoven’s cruel ‘Musikalischer Scherz’, ‘Lob auf den Dicken’ (Hymn to the Fat), was written in the same year as these sonatas. It begins with the soloists singing: “Schuppanzigh ist ein Lump, Lump, Lump…”

https://www.sheppardskaerved.com/listen/beethoven-sonata-op-30-no-1/

Posted on December 29th, 2009 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved